The Filipino-American War is also referred to as the Philippine-American War, the Philippine War, the Philippine Insurrection, or the Tagalog Insurgency. It was an armed conflict between the United States and the First Philippine Republic. The war lasted from February 4, 1899, to July 2, 1902. For Filipino nationalists, the war is a continuation of the struggle for independence that started in 1896 with the Philippine Revolution. However, for the Government of the United States, it is an insurrection or rebellion.

If you are interested to learn more about what happened in the war and the impact it had when it ended, you’re in the right place. Read on as we’re giving you the ultimate guide to the Filipino-American War.

Pre-War Events

Here are some of the events that occurred before the Filipino-American War began:

Philippine Revolution

On July 7, 1892, Andres Bonifacio, a warehouseman, and clerk from Manila, established the Katipunan. It was a revolutionary organization that was made to gain freedom from Spanish colonial rule by armed rebellion. Fighters in Cavite province won early victories with their popular leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, mayor of Cavite El Viejo, which is now known as Kawit, Cavite. With this, he gained control of a large part of the eastern portion of Cavite province. Eventually, he and his group gained control of the leadership of the Katipunan movement.

On March 22, 1897, Emilio Aguinaldo was elected president of the Philippine revolutionary movement at the Tejeros Convention. Bonifacio was executed by his supporters for treason after a show trial on May 10, 1897. With this, Emilio Aguinaldo is officially considered the first President of the Philippines.

The Exile and Return of Aguinaldo

After a series of defeats for the revolutionary forces in late 1897, the Spanish have regained control over most of the Philippines. Emilio Aguinaldo and Spanish Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera entered into truce negotiations. An agreement was reached on December 14, 1897, wherein the Spanish colonial government would pay Aguinaldo $MXN800,000 in Manila. It would be in three installments if Aguinaldo would go into exile outside of the Philippines.

When the first of the three installments were received, Aguinaldo, along with 25 of his closest associates, left their headquarters at Biak-na-Bato and went to Hong Kong. Before he left, he condemned the Philippine Revolution, encouraged Filipino rebel combatants to remove weapons, and stated those who continued warfare and pursuing war to be outlaws. However, despite his condemnation, some of the revolutionaries continued their armed revolt against the Spanish colonial government. According to Aguinaldo, the Spanish failed to pay the second and third installments of the agreed-upon amount.

After four months in exile, Emilio Aguinaldo resumed his role in the Philippine Revolution. On April 27, 1989, he left from Singapore aboard the steamship Malaca. He arrived in Hong Kong on May 1, which was also the day that US Commodore George Dewy’s naval forces destroyed Rear-Admiral Patricio Montojo’s Spanish Pacific Squadron during the Battle of Manila Bay. On May 17, Aguinaldo left Hong Kong aboard the USRC McCulloh and arrived in Cavite on May 19. You can read more about this in our post, Emilio Aguinaldo Returns.

In less than three months after Aguinaldo had returned, the Philippine Revolutionary Army had conquered almost all of the Philippines, except Manila, which was surrounded by revolutionary forces. More than 15,00 Spanish prisoners were turned over by Aguinaldo to the Americans, offering them valuable intelligence.

On June 12, 1898, Emilio Aguinaldo declared independence at his house in Cavite El Viejo. However, this Philippine Independence declaration was not recognized by either the United States or Spain. The Spanish government yielded the Philippines to the United States in the 1898 Treaty of Paris, and it was signed on December 10, 1898.

Emilio Aguinaldo was declared President of the Philippines on January 1, 1899. He was the only president of what would be later called the First Philippine Republic. Later on, he organized a congress in Malolos, Bulacan, to draft a constitution. You can read more about this in our article, Malolos Congress.

Origins of Conflict

Emilio Aguinaldo had a private meeting with United States Consul E, Spencer Pratt, in Singapore on April 22, 1898, while he was in exile. This was after he decided to take up once again the mantle of leadership in the Philippine Revolution. Aguinaldo stated that Pratt had communicated with Commodore George Dewey, the commander of the Asiatic Squadron of the US Navy, and passed pledges from Dewey to Aguinaldo that the US would distinguish the independence of the Philippines under the protection of the US Navy.

According to Pratt, there was no necessity for entering into a formal written agreement as the word of the Admiral of the United States Consul were equal to the official word of the government of the United States. With these guarantees, Aguinaldo settled to go back to the Philippines. However, later on, Pratt opposed Aguinaldo’s justification of these events, and he denied any dealings of a political character with the leader. Aside from that, Admiral Dewey also disproved Aguinaldo’s explanation, saying that they did not promise anything regarding the future.

Based on the American apostasy by Filipino historian Teodoro Agoncillo, it was the Americans who first approached Emilio Aguinaldo in Hong Kong and Singapore to encourage him to cooperate with Dewey in gaining power from the Spanish. Granting that Dewey may not have promised Aguinaldo American recognition and Philippine Independence as he had no power to make such promises, he writes that Dewey and Aguinaldo had informal cooperation in fighting a common enemy.

However, Dewey breached that alliance as he made secret arrangements for a Spanish surrender to American forces. After the surrender was secured, he treated Aguinaldo badly. With this, Agoncillo concluded that the American attitude towards Aguinaldo presented that they went to the Philippines not as a friend but as an opponent pretending to be a friend.

Commodore Dewey and Brigadier General Wesley Merritt’s secret agreement with newly arrived Spanish Governor-General Fermin Jaudenes, along with his predecessor Basilio Augustin was for the Spanish forces to surrender only to the Americans and not to the Filipino revolutionaries. To save face, the surrender of the Spanish would take place after a mock batter in Manila wherein the Spanish would lose, and the Filipinos would not be permitted to enter the city. You can read more about this in our article about the Mock Battle of Manila.

After the capture of Manila, Aguinaldo was told frankly by the Americans that his army could not participate and would be fired upon when they crossed into the city. During these times, it became clear to Filipinos that the Americans were in the islands to stay.

President William McKinley delivered a proclamation of benevolent assimilation on December 12, 1989, relieving the mild sway of justice and right for a subjective rule for the greatest good of the governed. Learn more about this in our article, Benevolent Assimilation.

The appointed Military Governor of the Philippines during that time, who was Elwell Stephen Otis, delayed the publication of the benevolent assimilation. He then published an amended version on January 4, 1899, so as not to carry the connotations of the terms sovereignty, protection, and right of cessation, which were included in the original version. However, Brigadier General Marcus Miller did not know about the edited version that had been published by Otis. With this, he passed a copy of the original proclamation to a Filipino official in Iloilo City.

On the revised proclamation that was issued the same day, Emilio Aguinaldo protested. His proclamations were regarded by Otis as equivalent to war, alerting his troops and strengthening observation posts. Aguinaldo’s proclamations, on the other hand, thrilled the masses with a strong fortitude to fight what was perceived as a friend-turned opponent.

War

Here are the important events that occurred during the Filipino-American War:

The Outbreak of War

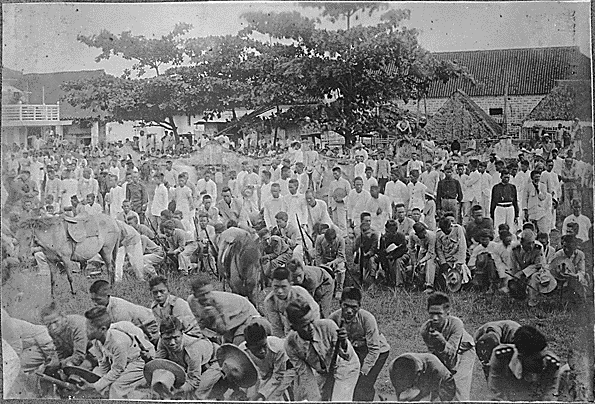

On the evening of February 4, 1899, the first shots of the war were fired at the corner of Sociego and Silencio Streets in Santa Mesa by Private William W. Grayson, a sentinel of the 1st Nebraska Volunteer Infantry Regiment. With this opening fire, he killed a Filipino lieutenant and a Filipino soldier. According to Filipino historians, the soldiers that were killed were unarmed. This triggered the 1899 Battle of Manila. Read more about how the war started in our article, Fil-Am War Breaks Out.

The following day, February 5, 1899, Filipino General Isidoro Torres came through the lines under a flag of truce to send a message from Aguinaldo to Otis that the fighting had accidentally begun and that Aguinaldo wished for the conflicts to cease immediately and for the formation of a neutral zone between the opposing forces. However, these overtures were dismissed by Otis, saying that the fighting had begun and must go on to the grim end. To find out more about what happened, read our article, War Escalates.

Guerilla War Phase

For most of 1899, the revolutionary leadership had seen guerilla warfare deliberately only as a pre-emptive choice of final recourse and not as a means of operation which suited their destitute situation. On November 13, 1899, Emilio Aguinaldo commanded that guerilla war would henceforward be the strategy. This made the American occupation of the Philippines more difficult over the next few years. Learn more about this in our article about the Guerilla Warfare, 1899.

Martial Law

General Arthur MacArthur Jr., who took the place of Elwell Otis as the United States Military Governor on May 5, placed the Philippines under martial law on December 20, 1900, which invoked U.S. Army General Order 100. He proclaimed that guerilla abuses would no longer be tolerated. He also outlined the rights which would govern the U.S. Army’s behavior towards guerillas and civilians.

To be specific, guerillas who did not wear uniform but peasant dress and changed from civilian to military status would be held accountable. Also, the secret committees that collected revolutionary taxes and those who were accepting protection from the U.S. in occupied towns while supporting guerillas would be treated as war traitors. The Filipino leaders who continuously worked towards Philippine independence were expatriated to Guam.

The Decline and Fall of the First Philippine Republic

During the conventional warfare phase, the Philippine Army continued to suffer defeats from the better-armed United States Army. This forced Emilio Aguinaldo to change his base of operations endlessly during the course of the war.

General Frederick Funston, along with his troops, captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela, on March 23, 1901, with the help of the Filipinos called the Macabebe Scouts, who joined the Americans’ side. The Americans pretended to be hostages of the Scouts, who were wearing Philippine Army uniforms. When Funston and the Scouts entered Aguinaldo’s camp, they fell upon the guards instantly and rapidly stunned them and the exhausted Aguinaldo. For more details about this incident, read our article about the Capture of Aguinaldo.

The capture of Aguinaldo caused a severe misfortune to the Filipino cause, but not as much as the Americans had anticipated. General Miguel Malvar, a Filipino general, took over the leadership of what remained of the Filipino government. Before, he had taken a defensive attitude against the Americans. But then, he launched an all-out offensive against the American-held towns in the Batangas region. Other army officers sustained the war in their corresponding areas.

On April 16, 1902, Malvar surrendered, together with his sick wife and children and some of his officers, as General Bell persistently pursued him and his men. By the end of April 1902, about 3,000 of Malvar’s men had also surrendered. With this, the Filipino war effort started to decline even further. You can read more details about this in our article about The War in 1900-1901.

Official End of the War

On July 1, 1902, The Philippine Organic Act was approved. It collated President McKinley’s previous executive order, which had established the Second Philippine Commission. The act also detailed that a government would be established composed of a generally voted lower house, an upper house, and the Philippine Assembly with the Philippine Commission. It also provided for extending the United States Bill of Rights to Filipinos.

The United States Secretary of War announced that since the insurgency contrary to the United States was over, and provincial civil governments had been established throughout most of the Philippine archipelago on July 2, 1902, the office of military governor was terminated. Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the United States presidency after President McKinley was assassinated, declared a pardon for those who had partaken in the conflict.

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that it was on April 16, 1902, when the Philippine-American War had ended, when General Miguel Malvar surrendered.

Casualties

The number of Filipino who died during the war still remains a matter of debate. But based on modern sources, there were about 200,000 total Filipino civilians who died, but most losses were attributable to famine and disease. There are some who estimate that it reached a million. Based on the General Geography of the Philippine Islands written by Manuel Arellano, there were at least an estimated 16,000-20,000 Filipino soldiers and 34,000 civilians who were killed, with up to 200,000 civilian deaths due to a cholera epidemic.

According to the United States Department of State, the war resulted in the death of more than 4,200 Americans and more than 20,000 Filipino combatants. In addition to that, as many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died from famine, disease, and violence.

Post-War

When the military rule was terminated on July 4, 1902, the Philippine Constabulary was a police force made for the whole archipelago to control brigandage and deal with the odds and ends of the insurgent movement. This slowly took over the responsibility for suppressing guerilla and bandit activities from United States Army units.

For nearly a decade after the war officially ended, fragments of the Katipunan and other resistance groups stayed vigorous fighting the United States military or Philippine Constabulary. However, Governor-General Taft preferred to rely on the Philippine Constabulary and to after the close of the war, and as well as to treat the Irreconcilables as a law enforcement concern instead of a military concern that needed the involvement of the American army.

Conclusion

There were indeed a lot of events that occurred during the Filipino-American War. It also had a huge impact on the culture of the Philippines. One of the major contributions of America to the Philippines is the firm establishment of education. In fact, some of the schools in the Philippines were opened by Thomasites, who were teachers from the United States. Some of these schools were the Philippine Normal School, which is now known as Philippine Normal University, the Philippine School of Arts and Trades, and the Philippine Nautical School.

In addition to the details given in this article, there were many more events that occurred during the Filipino-American War. If you’d like to learn more about it, here are some useful links that you may visit:

- US Ratifies Paris Treaty

- US Infantry to Manila

- US Infantry Arrives

- Trapping Aguinaldo, 1899

- The War Rages, 1899

- The War in the Visayas

- The Last Holdouts

- Stalling Moro Resistance

- Spanish Holdouts

- Spanish Courts of Law

- South of Manila Campaign

- Second Battle of Manila

- Combat in Manila Suburbs

- Mabini is Captured, 1899

- Luna Assassination

- Lawton’s Lake Expedition

- “Ilustrados” Collaborate

- Ilocos and Cagayan, 1899

- Gen. Lawton Dies, 1899

- Filipinos Negotiate

- Fil-Am War Breaks Out

- Collapse, 1901

- Capture of Calamba

- Battles at San Fernando

- Battle of San Roque

- Battle of Caloocan

- Battle of Angeles

- Balangiga Massacre, September 28, 1901

- Background: The Philippine Revolution and The Spanish-American War

- Americans Take Antipolo

- Americans Occupy Manila, August 13, 1899

- Americans Capture Malolos, March 30-31, 1899

- Aguinaldo in Later Years, 1902-1964

- Advance to San Isidro

- Advance to San Fernando

- Advance to Malolos