Nov. 12, 1899: Aguinaldo shifts to Guerilla Warfare

By the closing months of 1899, the army of the Philippine Republic was no longer a regular fighting force.

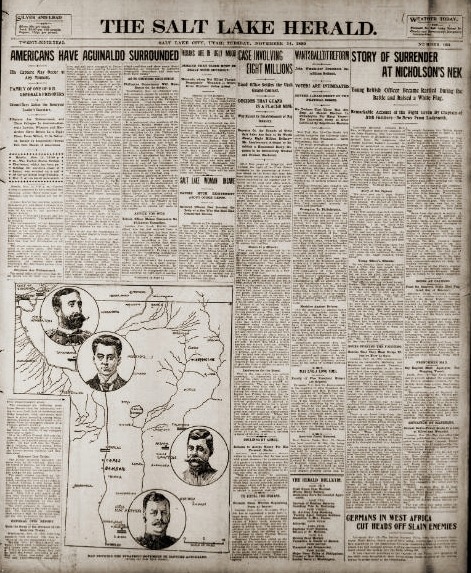

President Emilio Aguinaldo himself was under siege in Pangasinan Province from three pursuing American generals, from the north by Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton, from the south by Brig. Gen. Arthur MacArthur, Jr., and from the east by Maj. Gen. Henry Lawton.

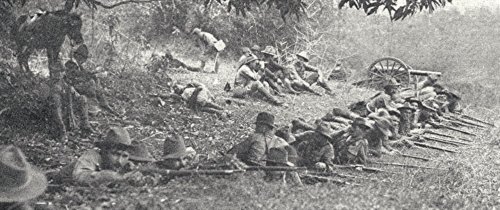

On Nov. 12, 1899, at a meeting of the council of war in Bayambang, the army was dissolved by Aguinaldo. It was formed into guerrilla units that would carry on the war unconventionally, relying on ambush, concealment, and the avoidance of set-piece battles.

The Wichita Daily Eagle, Wichita, Kansas, issue dated Nov. 11, 1899, quotes the La Independencia, official newspaper of the Philippine Republic

Aguinaldo, in a proclamation circulated among his troops, said:

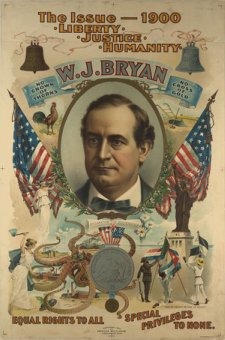

“In America there is a great party that insists on the Government recognizing Filipino Independence. That party will compel the United States to fulfil the promises made to us in all solemnity and good faith, though not put into writing. Therefore, we must show our gratitude and maintain our position more resolutely than ever.

“We should pray to God that the great Democratic party may win the next Presidential election and imperialism fall in its mad attempt to subjugate us by force of arms.”

He also denounced “the imperialists” in the United States, and declared that “we do not want war against the United States; we only defend our independence against the imperialists; the sons of that mighty nation are our friends and brothers.”

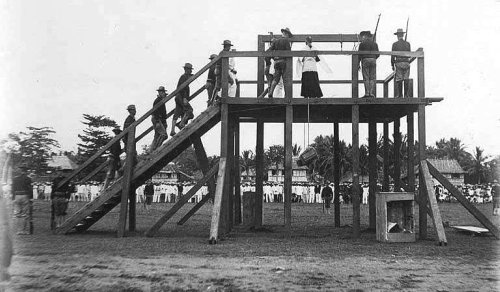

On Dec. 20, 1900, Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., declared in an official proclamation that since guerrilla warfare was contrary to “the customs and usages of war,” those engaged in it “divest themselves of the character of soldiers, and if captured are not entitled to the privileges of prisoners of war.” Less self-disciplined men found in the proclamation authorization for identifying Filipino fighters as outlaws and dealing with them accordingly.

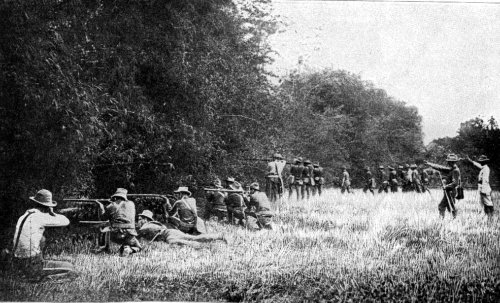

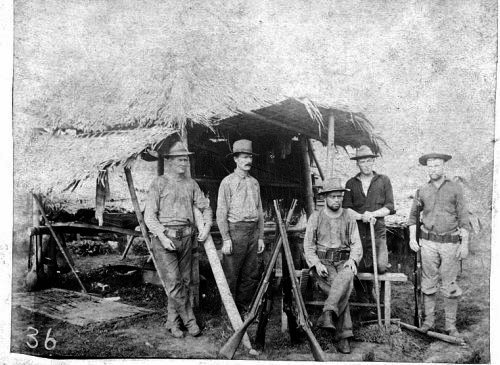

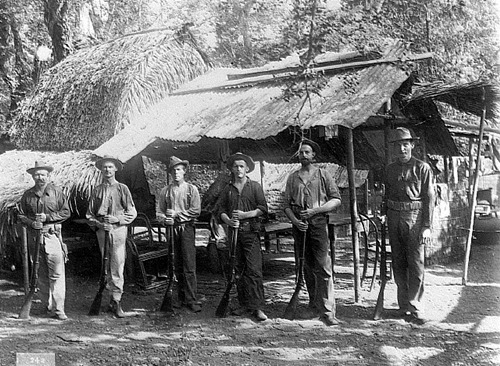

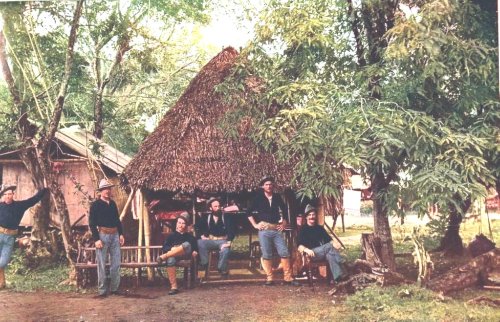

Filipinos blazing away at the Americans, 1899.

Official American reports claimed fifteen Filipinos killed for every one wounded; the historical norm was five wounded for every soldier killed. Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis explained this anomaly by the superior marksmanship of rural southerners and westerners who had hunted all their lives.

MacArthur added a racial twist, asserting that Anglo-Saxons do not succumb to wounds as easily as do men of “inferior races.”

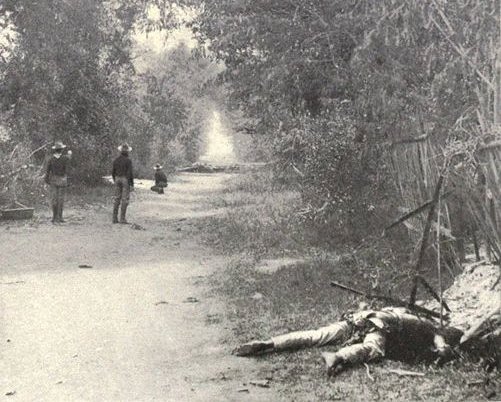

John Roberts, a bugler in the 13th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, said, “We have been vastly more cruel than the Spanish. I have known of orders being given which, if put in writing, would read, in effect: Let there be no wounded among the enemy.”

Richard E. Welch, Jr., a professor of history at Lafayette College, wrote that the Filipinos’ use of guerrilla tactics was the result of his inferior mind and his lowly race. He said, “…the American soldier viewed his Filipino enemies with contempt because of their short stature and color. Contempt was also occasioned by the refusal of the Filipino ‘to fight fair’- to stand his ground and be shot down like a man. When the Filipino adopted guerrilla tactics, it was because he was by his very nature half-savage and half-bandit. His practice of fighting with a bolo on one day and assuming the guise of a peaceful villager on the next proved his depravity.”

Charles Ballantine of the Associated Press stated that the Filipinos were “unreliable, untrustworthy, ignorant, vicious, immoral and lazy . . . tricky, and, as a race more dishonest than any known race on the face of the earth.”

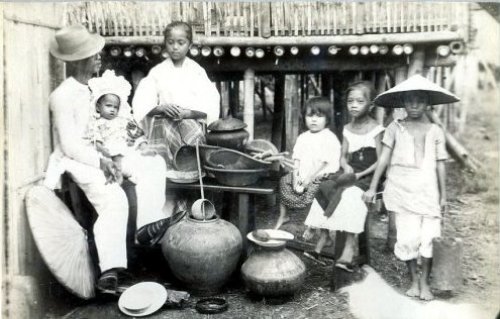

U.S. military forays descended into a series of atrocities that included the massacre of prisoners, civilian and military, and entire villages. General William Shafter told a journalist it might be necessary to kill half the native population to bring �perfect justice� to the other half.

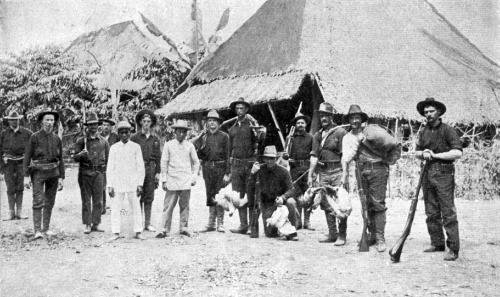

Leonard F. Adams, 1st Washington Volunteers, wrote home about a campaign in Luzon: “In the path of the Washington regiment..there were 1,008 dead niggers and a great many wounded. We burned all their houses. I don’t know how many men, women and children the Tennessee boys did kill. They would not take any prisoners. One company of the Tennessee boys was sent to headquarters with thirty prisoners, and got there with about a hundred chickens and no prisoners.”

General Robert Hughes, U.S. commander in Manila, justified the Army’s atrocities against civilians: �The women and children are part of the family and where you wish to inflict punishment you can punish the man probably worse in that way than in any other.�

The San Francisco Argonaut, an influential Republican newspaper, spoke candidly: “We do not want the Filipinos. We want the Philippines. The islands are enormously rich, but unfortunately they are infested with Filipinos. There are many millions there, and it is to be feared their extinction will be slow.” The paper’s solution was to recommend several unusually cruel methods of torture it believed “would impress the Malay mind” ���the rack, the thumbscrew, the trial by fire, the trial by molten lead, boiling insurgents alive.�

The advice was well taken. The Baltimore American had to admit the U.S. occupation �aped� Spain’s cruelty and committed crimes �we went to war to banish.�

American historian Leon Wolff quoted an observer, “Even the Spaniards are appalled at American cruelty.”