US Infantry Troops Arrive In The Philippines, June 30 – July 31, 1898

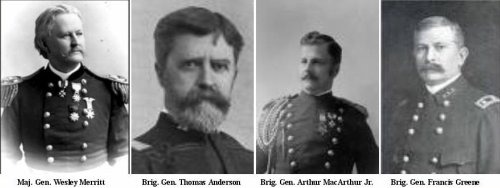

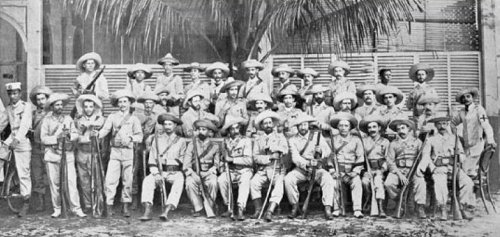

The first American infantry troops arrived in the Philippines on June 30, 1898. They were commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Anderson. [He was a son of Maj. Gen. Robert Anderson, who had commanded Fort Sumter at the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861].

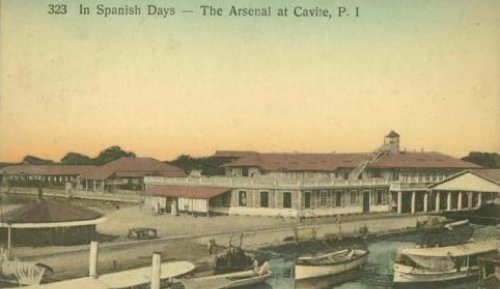

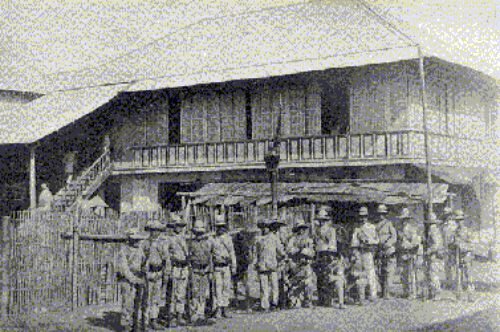

With Aguinaldo’s consent, they were assigned to the arsenal and Fort San Felipe Neri in Cavite Province.

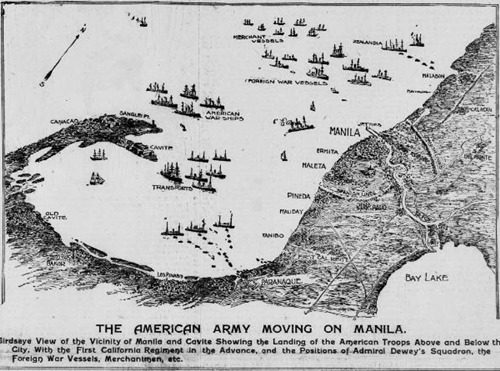

General Anderson located the outer and inner lines of the Spanish defenses of Manila. It was decided that a joint naval-infantry attack could best be made from the south, and to secure that line of advance pending the arrival of General Merritt, a camp site was selected on the bay shore at Tambo, Paranaque, about 3 miles (5 km) south of Malate, Manila. It was an abandoned peanut farm that offered good access to Manila and easy egress to the sea.

A day or two later Aguinaldo called on General Anderson; he was received with military honors. A company of the 14th US Regulars presented arms as he came to the headquarters building, and the trumpeters blew the General’s salute.

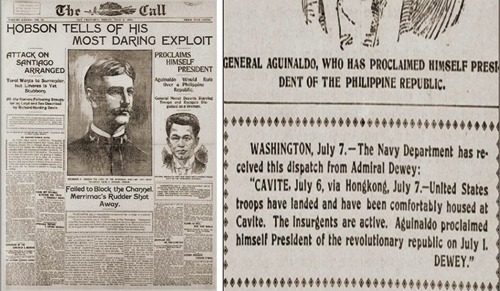

He had no confidences to exchange. Aguinaldo asked directly what the Americans intended to do in regard to the Philippines.

“We have lived as a nation 122 years,” replied General Anderson, through his interpreter, “and have never owned or desired a colony. We consider ourselves a great nation as we are, and 1 leave you to draw your own inference.”

Aguinaldo said to his interpreter:

“Tell General Anderson that I do not fear that the Americans will annex the Philippines, because I have read their Constitution many times and I do not find a provision there for annexation or colonization.”

On July 15 one battalion of 1st California volunteers was placed at Tambo and a depot of supply and transportation established. Two days later, the two remaining battalions of the 1st California regiment were sent over from Cavite, and the camp — first called Camp Tambo — was renamed Camp Dewey, in honor of the commander of the naval squadron.

On July 17 and 31, the second and third expeditions, under Brigadier-Generals Felix V. Greene and Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., respectively, arrived in Cavite harbor and were transferred to Camp Dewey, the transfer being completed about August 9.

By this time, 470 officers and 10,464 infantry troops had been stationed in the country.

He found General Anderson’s headquarters, with the California Heavy Artillery, 14th and 23rd United States Infantry, and the 2nd Oregon Volunteers, at Cavite; while General Greene was encamped with his brigade at Camp Dewey.

The left, or north, flank of General Greene’s camp extended to a point on Calle Real (now M.H. Del Pilar St.) about 3,000 yards (meters) from Fort San Antonio de Abad (ABOVE, in February 1899), a polvorin or powder magazine close to the beach at the southern end of Malate, which formed the right extremity of the outer line of the Spanish defenses of Manila.

From Fort San Antonio de Abad the Spanish lines extended to the left, eastward, in trenches and blockhouses, through swamps and ricefields, encircling Manila and covering all avenues of approach from the land side.

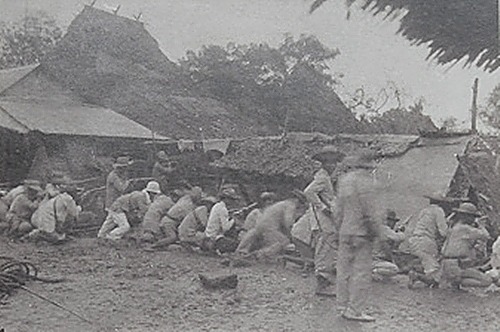

The Filipinos occupied positions facing these lines throughout their extent. On Calle Real (now M.H. Del Pilar St.) , the road passing Camp Dewey parallel to the beach, the Filipinos had established an earthwork about 800 yards from Fort San Antonio de Abad. They also had possession of the approach by the beach proper, and occupied the Pasay-Manila road, parallel to Calle Real, and about 700 yards to the eastward of it. The outposts of General Greene’s camp were posted in rear of the Filipinos.

The Filipinos were persuaded to withdraw from Calle Real in order that the American troops could move forward; the former moved to the east of Calle Real, and the trenches from the beach to Calle Real were occupied by Greene’s outposts on July 29. On the right were detached barricades occupied by the Filipinos, extending over to the rice swamp just east of the Pasay road.

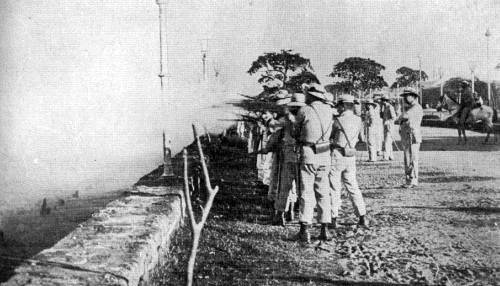

Facing these, the Spanish works of earth and sand bags, 7 feet high and 10 feet thick, stretched to the eastward, with a slightly concave trace, to Blockhouse 14, a strongly fortified position on the Pasay road, and distant about 1,200 yards from Fort San Antonio de Abad, thus enveloping the American right. Seven guns were mounted in the stone fort on the Spanish right, and two steel 3.2-inch mountain guns near Blockhouse 14; the line was manned throughout its length by infantry, with strong reserves in Malate and Intramuros.

On July 31, shortly before midnight, the Spaniards opened a heavy and continuous fire with infantry and artillery from their entire line.

Battery H, 3rd Artillery, the 10th Pennsylvania Volunteers, and 4 guns of batteries A and B, Utah Artillery were in the trenches at the time and sustained the attack for an hour and a half, being reinforced by 1 battalion of 1st California Volunteers and Battery K, 3rd Artillery. The firing ceased at about 2 A. M. The casualties on the American side were 10 killed and 43 wounded.

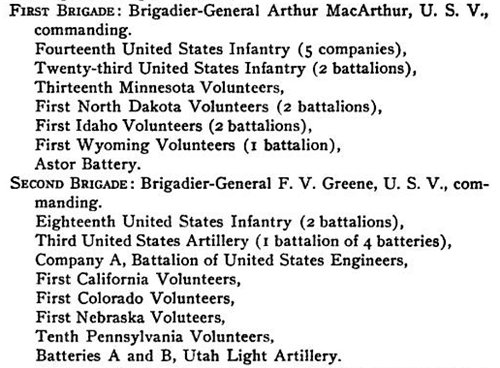

On August 1, General Merritt organized the American troops into one division (interestingly enough named the 2nd Division; there was no 1st Division) commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Anderson. Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., commanded the 1st Brigade and Brig. Gen. Francis V. Greene (West Point Class 1870) commanded the 2nd Brigade.

The brigades and their components:

On the nights of August 1, 2, and 5, the Spaniards opened up again with infantry and artillery fire; one American soldier was killed.

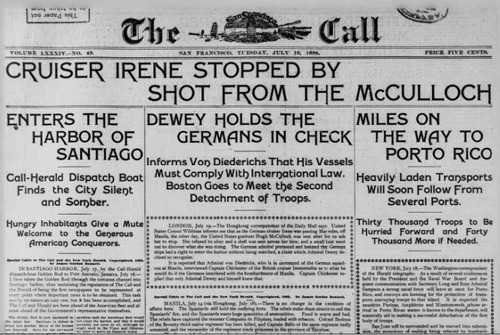

On August 7, General MacArthur’s brigade being in position, and the USS Monterey, for which the navy had been waiting, having arrived, General Merritt and Admiral Dewey sent to the Spanish Governor-General in Manila a joint letter warning him to remove all non-combatants from the city within 48 hours, and notifying him that operations against Manila might begin at any time after the expiration of that period.

The Governor-General replied that on account of being surrounded by the Filipino forces there was no place to which they could safely send their sick, wounded, women, and children.

Merritt and Dewey purposefully left Emilio Aguinaldo out of any plans and preparations regarding the capture of Manila.

On August 9, a formal joint demand was made for the surrender of Manila, based upon the hopelessness of the Spanish situation without possibility of relief, and upon considerations of humanity dictating the avoidance of the useless sacrifice of life entailed in an assault and possible bombardment.

The Spanish cause was doomed, but Fermín Jaudenes (LEFT, in 1898), who had replaced Basilio de Agustin as Governor-General on August 4, devised a way to salvage the honor of his country. Negotiations were carried out through Belgian consul Edouard Andre.

A secret agreement was made between the governor and American military commanders concerning the capture of Manila.

The Spaniards would put up only a show of resistance and, on a prearranged signal, would surrender. In this way, the governor would be spared the ignominy of giving up without a fight. American forces would neither bombard the city nor allow the Filipinos to take part; the Spanish feared that the Filipinos were plotting to massacre them all.

For centuries the Spanish had ruled the Philippines with a heavy—often deadly—hand. They considered the Filipino people to be ruthless, uncivilized, and sub-human. There was great fear that if the city fell to Aguinaldo and his revolutionary forces, there would be hell to pay.

On August 11, a Filipino regiment in the Spanish army was suspected of being about to desert. The Spanish officers picked out six corporals and had them shot dead. Next night the whole regiment went over to Aguinaldo’s army with their arms and accoutrements.

On August 12, fighting between American and Filipino troops almost broke out as the former moved in to dislodge the latter from strategic positions around Manila. Brig. Gen. Thomas Anderson telegraphed Aguinaldo, “Do not let your troops enter Manila without the permission of the American commander. On this side of the Pasig River you will be under fire.”