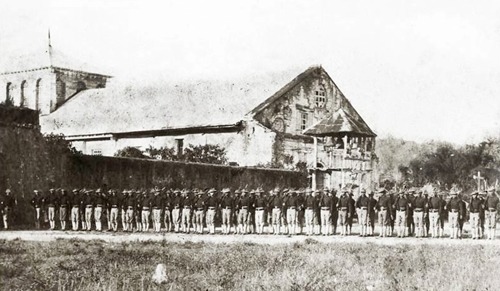

A glamour unit, Company C was assigned provost duty and guarded the captured President Emilio Aguinaldo upon their return to the Philippines on June 5, 1901, after fighting Boxer rebels and helping capture Peking in China.

They also performed as honor guard during the historic July 4, 1901 inauguration of the American civil government in the Philippines and the installation as first civil governor of William Howard Taft, later president of the U.S.

Filipino historian, Prof. Rolando O. Borrinaga, tells the story of the massacre in an article entitled “Vintage View: The Balangiga Incident and Its Aftermath“:

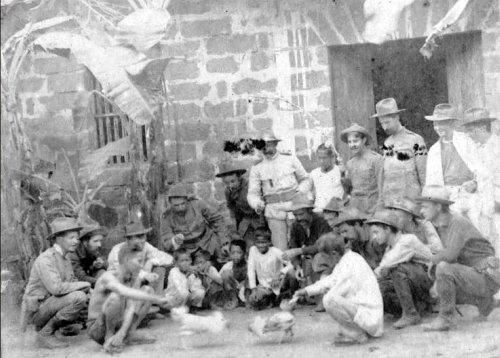

“The first month of Company C�s presence in Balangiga was marked by extensive fraternization between the Americans and the local residents. The friendly activities included tuba (native wine) drinking among the soldiers and native males, baseball games and arnis (stick fighting) demonstrations in the town plaza, and even a romantic link between an American sergeant, Frank Betron, and a native woman church leader, Casiana �Geronima� Nacionales.

“Tensions rose when on September 22, at a tuba store, two drunken American soldiers tried to molest the girl tending the store. The girl was rescued by her two brothers, who mauled the soldiers. In retaliation, the Company Commander, Capt. Thomas W. Connell, West Point class of 1894, rounded up 143 male residents for forced labor to clean up the town in preparation for an official visit by his superior officers. They were detained overnight without food under two conical Sibley tents in the town plaza, each of which could only accommodate 16 persons; 78 of the detainees remained the next morning, after 65 others were released due to age and physical infirmity. Finally, Connell ordered the confiscation from their houses of all sharp bolos, and the confiscation and destruction of stored rice. Feeling aggrieved, the townspeople plotted to attack the U.S. Army garrison.

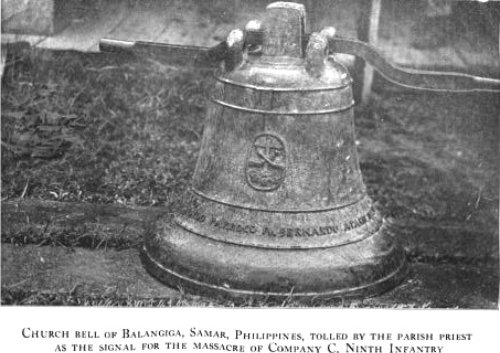

“On September 27, Friday, the natives sought divine help and intervention for the success of their plot through an afternoon procession and marathon evening novena prayers to their protector saints inside the church. They also ensured the safety of the women and children by having them leave the town after midnight, hours before the attack. Pvt. Adolph Gamlin observed women and children evacuating the town and reported it, but he was ignored.

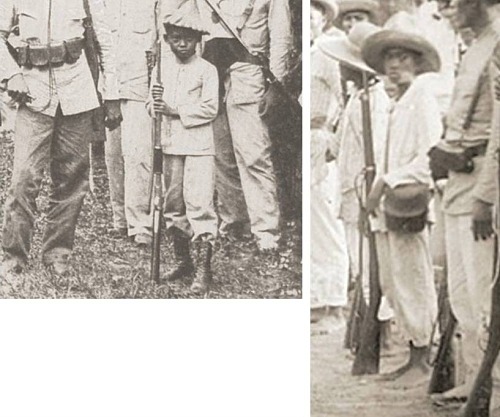

“To mask the disappearance of the women from the dawn service inside the church, 34 attackers from Barrio Lawaan cross-dressed as women worshippers.

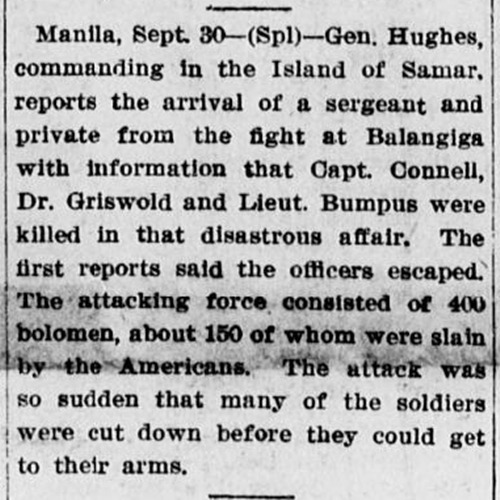

“The guards outside the convent and municipal hall were killed. The Filipinos apparently sealed in the Sibley tents at the front of the municipal hall, having had weapons smuggled to them in water carriers, broke free and entered the municipal hall and made their way to the second floor. The men in the church broke into the convent through a connecting corridor and killed the officers who were billeted there. The mess tent and the two barracks were attacked. Most of the Americans were hacked to death before they could grab their firearms. The few who escaped the main attack fought with kitchen utensils, steak knives, and chairs.

“The convent was successfully occupied and so, initially, was the municipal hall, but the mess tent and barracks attack suffered a fatal flaw – about one hundred men were split into three groups, one of each target but too few attackers had been assigned to ensure success. A number of Co. C. personnel escaped from the mess tent and the barracks and were able to retake the municipal hall, arm themselves and fight back. Adolph Gamlin recovered consciousness, found a rifle and caused considerable casualties among the Filipinos. [Gamlin died at age 92 in the U.S. in 1969].

“Faced with immensely superior firepower and a rapidly degrading attack, Abanador ordered a retreat. But with insufficient numbers and fear that the rebels would re-group and attack again, the surviving Americans, led by Sgt. Frank Betron, escaped by baroto (native canoes with outriggers, navigated by using wooden paddles) to Basey, Samar, about 20 miles away. The townspeople returned to bury their dead, then abandoned the town.”

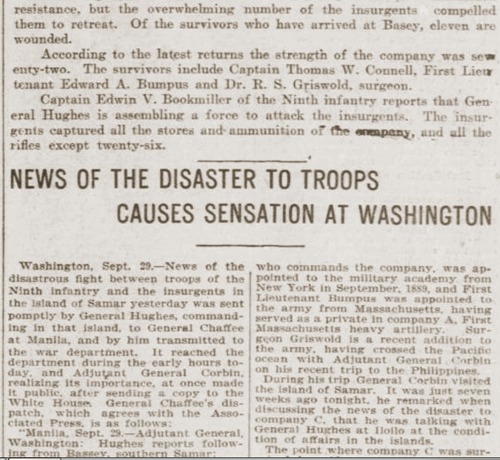

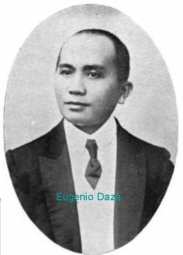

Of the original 74 man contingent, 48 died and 26 survived, 22 of them severely wounded. The dead included all of Company C’s commissioned officers: Capt. Thomas W. Connell (RIGHT), 1st Lt. Edward A. Bumpus, and Maj. Richard S. Griswold (the Company surgeon). The guerillas also took 100 rifles with 25,000 rounds of ammunition; 28 Filipinos died and 22 were wounded.

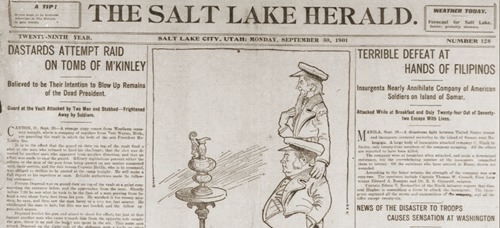

The massacre shocked the U.S. public; many newspaper editors noted that it was the worst disaster suffered by the U.S. Army since Custer’s last stand at Little Big Horn. An infuriated Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, military governor for the �unpacified� areas of the Philippines, assured the press that “the situation calls for shot, shells and bayonets as the natives are not to be trusted.” He advised newspaper correspondent Joseph Ohl, “If you should hear of a few Filipinos more or less being put away don’t grow too sentimental over it.”

Chaffee informed his officers that it was his intention “to give the Filipinos ‘bayonet rule’ for years to come.” President Theodore Roosevelt ordered Chaffee to adopt “in no unmistakable terms,” the “most stern measures to pacify Samar.”

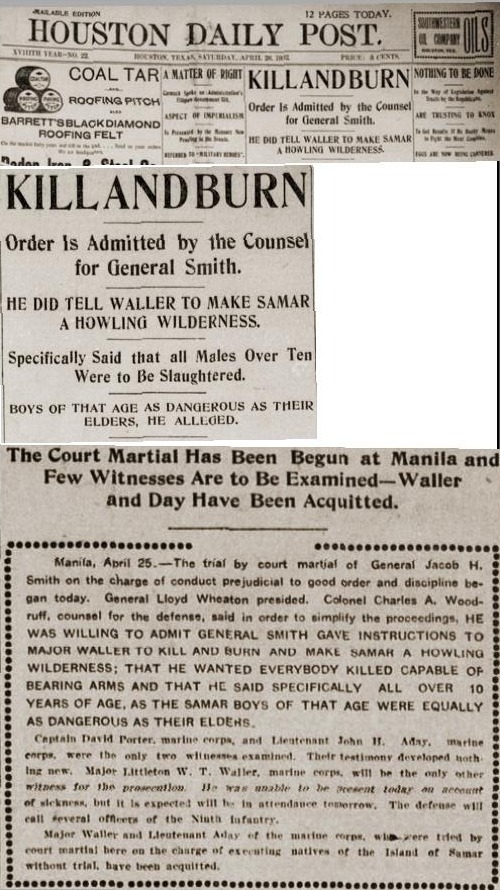

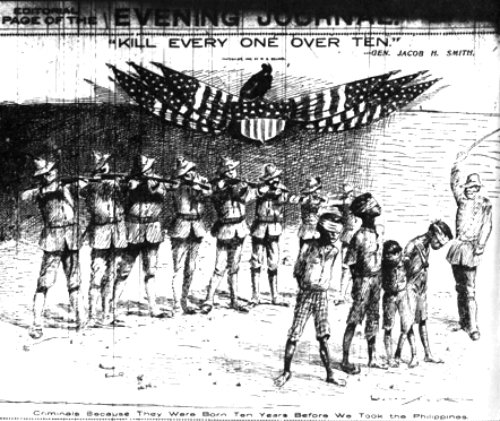

After the massacre at Balangiga, General Smith issued his infamous Circular No. 6, which stated his plans for crushing all resistance on the island of Samar.

He ordered his command thus:

“I want no prisoners” and “I wish you to kill and burn; and the more you burn and kill, the better it will please me.”

Then he tasked his men to reduce Samar into a “howling wilderness,” to kill anyone 10 years old and above capable of bearing arms.

He stressed that, “Every native will henceforth be treated as an enemy until he has conclusively shown that he is a friend.” His policy would be “to wage war in the sharpest and most decisive manner,” and that “a course would be pursued that would create a burning desire for peace.” [On Dec. 29, 1890, as a cavalryman, Smith was present at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, an incident —-also referred to as a massacre—-that left about 300 Sioux men, women and children, and 29 Army soldiers dead.]

In Samar, he gave his subordinates carte blanche authority in the application of Abraham Lincoln�s 1863 General Order 100. This order, in brief, authorized the shooting on sight of all persons not in uniform acting as soldiers and those committing, or seeking to commit, sabotage.

The exact number of civilians massacred by US troops will never be known, but exhaustive research made by a sympathetic British writer in the 1990s put the figure at about 2,500; Filipino historians believe it was around 50,000.

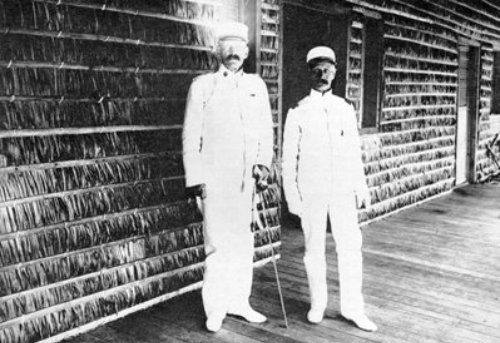

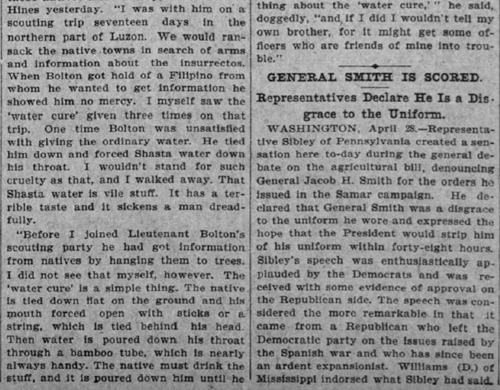

General Smith and Major Waller (RIGHT) underwent separate courts-martial for their roles in the suppressive campaign of Nov 1901- Jan 1902. Although he received the “Kill all over ten” order from Gen. Smith, Waller countermanded it and told his men not to obey it.

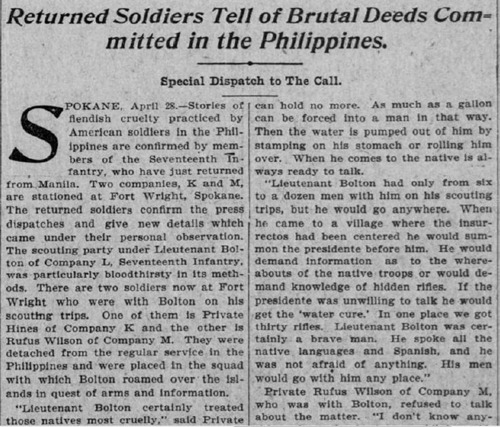

However, he was specifically tried for murder in the summary execution of 11 Filipino porters. After a long march, Marine Lt. A.S. Wlliams accused the porters of mutinuous behavior, hiding food and supplies and keeping themselves nourished from the jungle while the Marines starved. Waller ordered the execution of the porters. Ten were shot in groups of three, while one was gunned down in the water attempting to escape. The bodies were left in the square of Lanang (now Llorente), as an example, until one evening, under cover of darkness, some townspeople carried them off for a Christian burial.

In an eleven-day span, Major Waller also reported that his men burned 255 dwellings, slaughtered 13 carabaos and killed 39 people. Other officers reported similar activity.

Smith commanded the Sixth Separate Brigade, which included a battalion of 315 Marines under Waller. Waller’s court martial acquitted him but Smith’s found him guilty, for which he was admonished and retired from the service. Gen. Smith was born in 1840 and died in San Diego, California on March 1, 1918.

Outcry in America over the brutal nature of the Samar campaign cost Waller his chance at the Commandancy of the US Marine Corps. Liberal newspapers took to addressing him as “The Butcher Of Samar”.

Waller was born in York County, Virginia on Sept. 26, 1856. He was appointed as a second lieutenant of Marines on June 24, 1880. He rose to Major General, retired in June 1920 and died on July 13, 1926. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In 1942, the destroyer USS Waller was named in his honor.

In April 1902, Abanador accepted the general amnesty offered by the Americans. He died sometime in the 1950’s.

Dec. 27, 1901: Atrocity in Panay Island

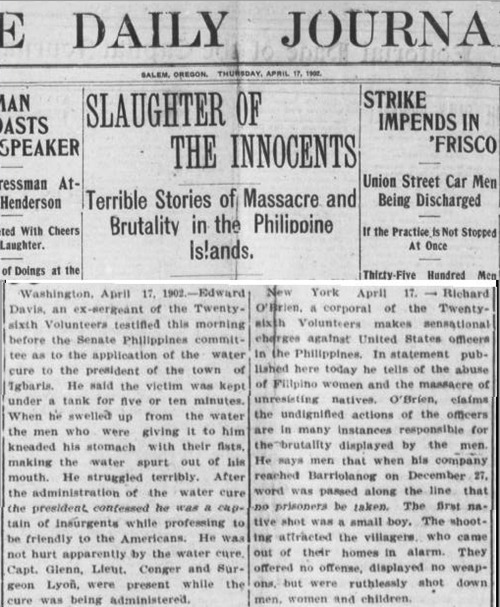

“It was on the 27th day of December, the anniversary of my birth, and I shall never forget the scenes I witnessed on that day. As we approached the town the word passed along the line that there would be no prisoners taken. It meant that we were to shoot every living thing in sight�man, woman, and child. The first shot was fired by the then first sergeant of our company. His target was a mere boy, who was coming down the mountain path into the town astride of a caribou. The boy was not struck by the bullet, but that was not the sergeant’s fault. The little Filipino boy slid from the back of his caribou and fled in terror up the mountain side. Half a dozen shots were fired after him. The shooting now had attracted the villagers, who came out of their homes in alarm, wondering what it all meant. They offered no offense, did not display a weapon, made no hostile movement whatsoever, but they were ruthlessly shot down in cold blood�men, women, and children. The poor natives huddled together or fled in terror. Many were pursued and killed on the spot.

“Two old men, bearing between them a white flag and clasping hands like two brothers, approached the lines. Their hair was white. They fairly tottered, they were so feeble under the weight of years. To my horror and that of the other men in the command, the order was given to fire, and the two old men were shot down in their tracks. We entered the village. A man who had been on a sick-bed appeared at the doorway of his home. He received a bullet in the abdomen and fell dead in the doorway. Dum-dum bullets were used in that massacre, but we were not told the name of the bullets. We didn’t have to be told. We knew what they were.

“In another part of the village a mother with a babe at her breast and two young children at her side pleaded for mercy. She feared to leave her home, which had just been fired�accidentally, I believe. She faced the flames with her children, and not a hand was raised to save her or the little ones. They perished miserably. It was sure death if she left the house�it was sure death if she remained. She feared the American soldiers, however, worse than the devouring flames.”

Company M was commanded by Capt. Fred McDonald.