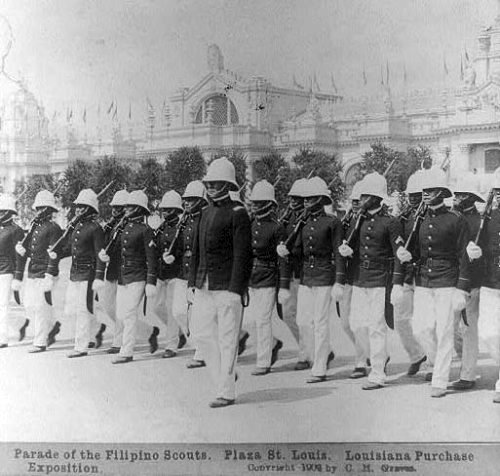

The Last Holdouts: General Vicente Lukban falls, Feb. 18, 1902

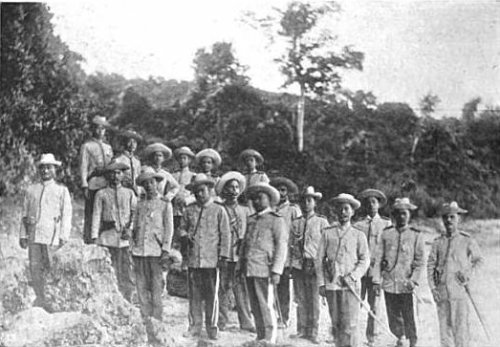

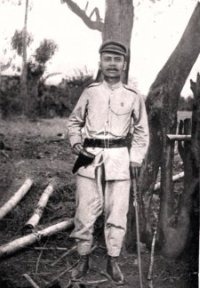

General Vicente Lukban commanded Filipino guerilla forces on Samar and Leyte islands in the eastern Visayas, central Philippines.

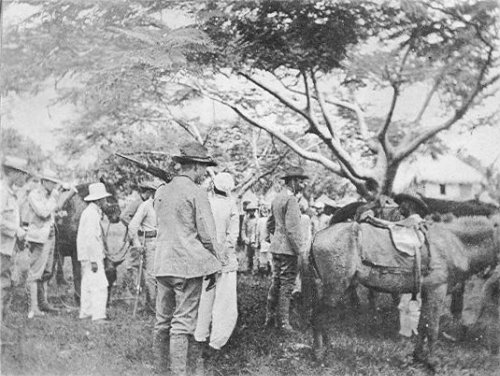

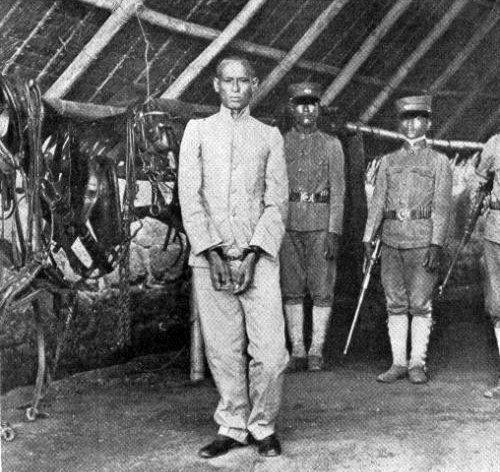

On Feb. 18, 1902, he was captured by a scouting party composed of Americans and Filipinos commanded by 1Lt. Alphonse Strebler of Company 39, Visayas, Philippine Scouts.

Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, military governor for the unpacified areas of the Philippines, ordered that Lukban be treated as a prisoner of war of officer’s rank.

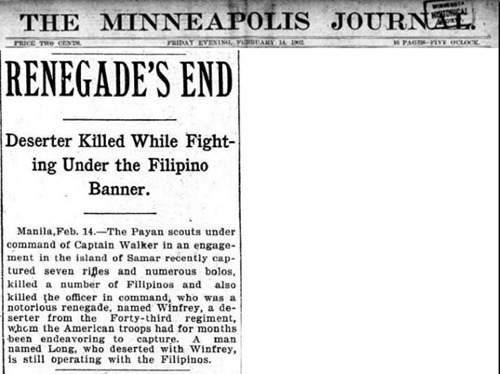

[Two weeks earlier, on Feb. 8, 1902, another white American deserter, John Winfrey, from the 43rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, was killed along with 8 Filipino guerillas in a clash with 1Lt. Allen Walker of Company 45, Visayas, Philippine Scouts.

The encounter took place in the vicinity of Loguilocon, Samar. On his body was found a commission as second lieutenant from Gen. Vicente Lukban.]

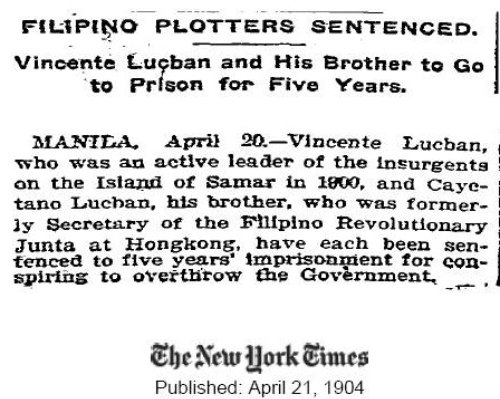

On Feb. 27, 1902, the New York Times reported:

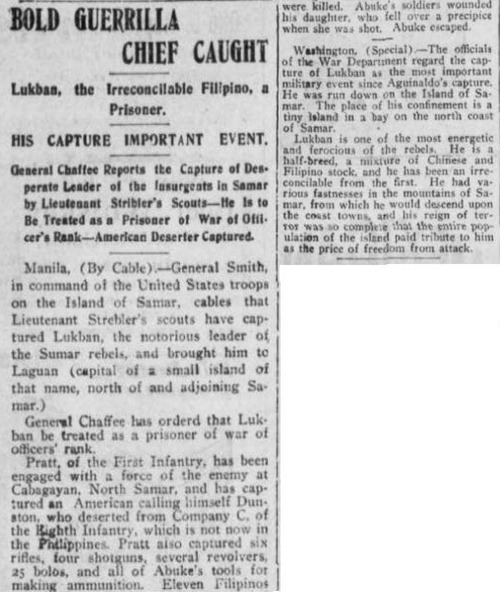

“The officials of the War Department regard the capture of Lucban as the most important military event since Aguinaldo’s capture. He was run down on the Island of Samar. The place of his confinement is a tiny island in a bay on the north coast of Samar. Lucban is one of the most energetic and ferocious of rebels. He is a half-breed, a mixture of Chinese and Filipino stock, and has been an irreconcilable from the first. He had various fastnesses in the mountains of Samar, from which he would descend upon the coast towns, and his reign of terror was so complete that the entire population of the island paid tribute to him as the price of freedom from attack.”

The Americans tagged Lukban as the mastermind of the infamous “Balangiga Massacre” on Sept. 28, 1901, in which 48 troopers of Company C, 9th U.S. Infantry Regiment, were killed. In fact, he played no part in the planning of the attack; he only learned about it a week later, on Oct. 6, 1901.

Lukban was born on Feb. 11, 1860 at Labo, Camarines Norte Province. After his elementary education at the Escuela Pia Publica in his hometown, he proceeded to Manila and completed his secondary schooling at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila. He took up Law at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran, and then worked in the Court of First Instance in Quiapo, Manila, before becoming Justice of the Peace in Labo.

In 1894, he was inducted into the Masonic Lodge adopting the name “Luz del Oriente” (Light of the Orient) and co-founded Bicol Lodge in Libmanan, Camarines Sur with Juan Miguel. He joined the secret revolutionary society Katipunan that same year.

In 1896, Lukban resigned from government service and engaged in business and agriculture. He founded the agricultural society La Cooperativa Popular.

On Sept. 29, 1896 Lukban was in Manila attending a meeting of the agricultural society when Spanish authorities arrested him for his involvement with the Katipunan. He was kept at the Carcel de Bilibid and despite torture did not expose his fellow revolutionaries. Torture and imprisonment in a flooded cell left him with a permanent limp. He was released on May 17, 1897 after Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera granted amnesty to political prisoners. He immediately joined General Emilio Aguinaldos forces.

In May 1898, Lukban returned to the Philippines and resumed his involvement with the revolutionists; he was given the rank of a Colonel. On Oct. 29, 1898, General Aguinaldo appointed him Comandante Militar of the Bicol region. On December 21 of the same year, he was promoted General of Samar and Leyte.

When the Filipino-American War broke out on Feb. 4, 1899, Lukban established his arsenal in the mountains of Catbalogan and carried out guerrilla warfare.

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., offered $5,000 (read as “Pesos”) for Lukbans head. He was offered the position of governor of Samar under the American regime, with autonomy, if he would surrender, but he refused to accept the offer.

After his capture, the Americans asked Lukban to use his influence and convince the rest of his command to surrender. He demurred at first, but subsequently changed his mind and wrote several letters, which were sent out and carried by pro-American Filipinos.

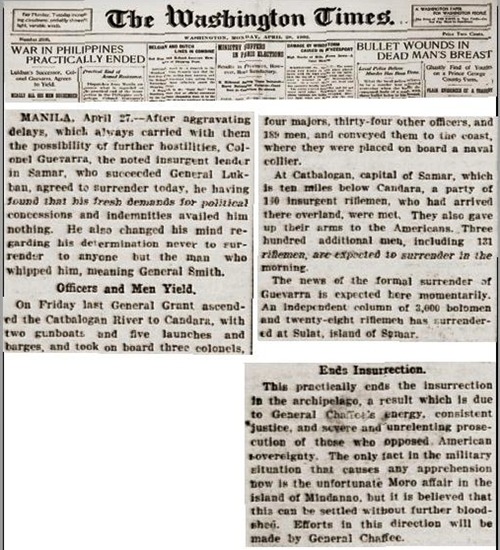

Col. Claro Guevarra succeeded Lukban and forbade his men to give attention to the latter’s letters. He assumed the rank of General and prepared to continue the resistance. The Americans sent peace envoys to negotiate with Guevarra.

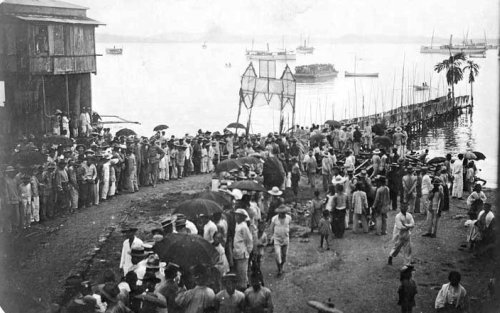

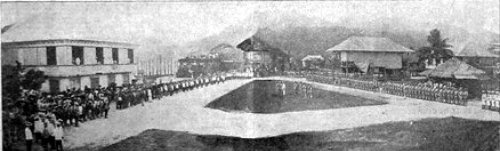

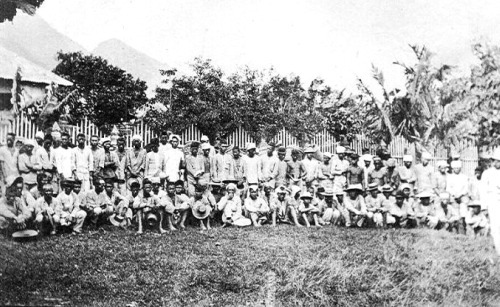

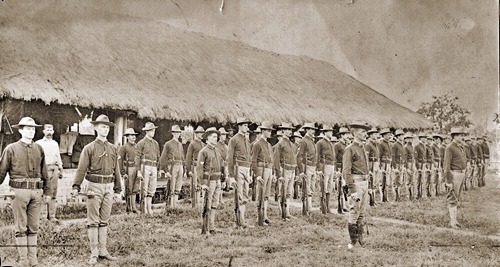

On April 26, 1902,Guevarra relented and the following day surrendered with 744 men to Brig. Gen. Frederick Dent Grant, commander of the Sixth US Infantry Brigade, at Catbalogan, Samar.

Guevarra’s entourage consisted of 65 officers, 236 riflemen and 443 boleros. A few days later, 5 more riflemen and 53 boleros also surrendered at Catbalogan. Arms and ammunition surrendered: 115 Krag rifles, 1 Krag carbine, 79 Remington rifles, 31 Mauser rifles, 14 miscellaneous guns; total, 240. Seven thousand five hundred rounds Krag cartridges, 500 miscellaneous; total, 8,000.

On May 11, 1902, 18 guerillas with 2 Remington rifles, 1 shotgun and 18 rounds of ammunition surrendered at Catbalogan. Two days later, Lt. Ignacio Alar, with 3 officers, 35 men, 12 Krag rifles, 1 Springfield rifle, 3 shotguns and 1,000 rounds of ammunition gave up at Tacloban. This last surrender accounted for every guerilla officer known then to the Americans in Samar, and for every rifle except two.

On June 17, 1902, provincial civil government was established on Samar Island by an act of the Philippine Commission.

In 1904, Lukban was arrested with two of his brothers, Justo and Cayetano, on charges of sedition filed against them by the Manila Secret Police. The Supreme Court, however, acquitted them for lack of evidence.

In 1912, Lukban ran for Governor in Tayabas and although not a native of the place, won handily (His mother, though, was born in Lucban, Tayabas). He was reelected for another term in 1916 but died on November 16 of the same year.

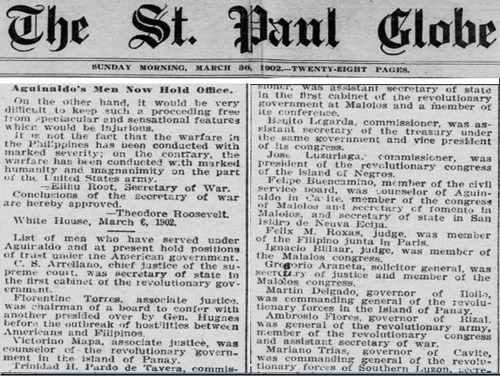

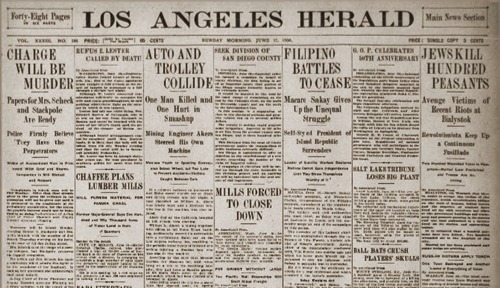

March 30, 1902: US Newspaper Lists Filipino Collaborators

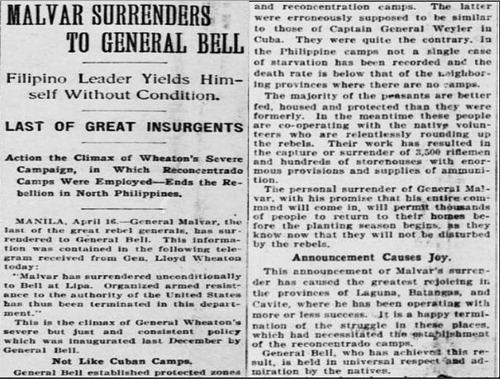

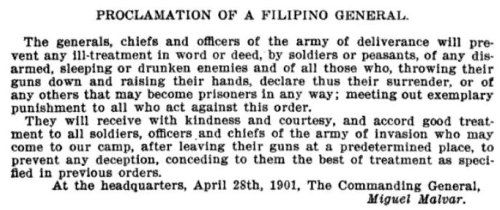

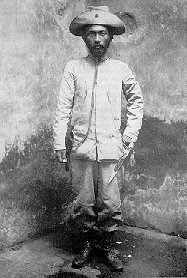

Gen. Miguel Malvar surrenders, April 16, 1902

General Miguel Malvar was born on Sept 27, 1865 in Santo Tomas, Batangas Province, to a wealthy sugarcane and rice farming family. He was one of the generals exiled with Emilio Aguinaldo to Hongkong as a result of the Pact of Biyak-na-Bato forged on Dec. 14, 1897 between Spain and the Filipino rebels. He was appointed treasurer of the revolution’s funds. When the truce collapsed, Malvar returned to the Philippines with 2,000 rifles and 200,000 rounds of ammunition. He liberated Tayabas Province from the Spaniards on June 15, 1898.

After Aguinaldo’s capture by the Americans on March 23, 1901, Malvar assumed control of all the Filipino forces. He setup his own government of the Philippine Republic, with him as supreme head and Commander-in-Chief, and waged guerilla warfare against American-held towns in Batangas.

Brig. Gen. James Franklin Bell, in charge of military operations on Luzon Island, employed scorched earth tactics that took a heavy toll on Filipino guerrillas and civilians alike.

He told the New York Times on May 1, 1901, that:

“One-sixth of the natives of Luzon have either been killed or have died of the dengue fever in the last two years. The loss of life by killing alone has been great, but I think that not one man has been slain except where his death served the legitimate purposes of war. It has been necessary to adopt what other countries would probably be thought harsh measures, for the Filipino is tricky and crafty and has to be fought in his own way.”

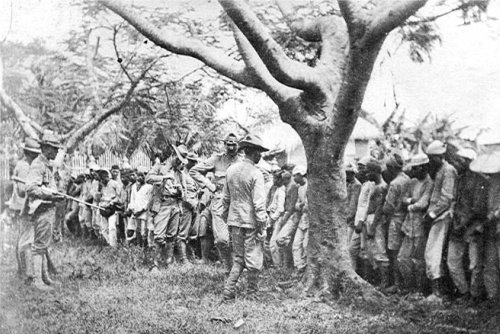

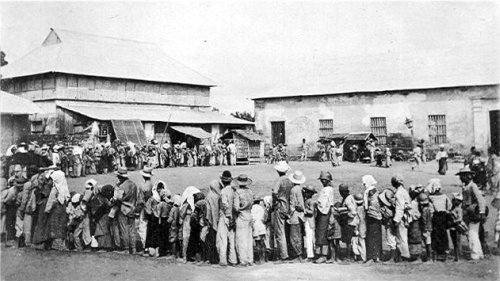

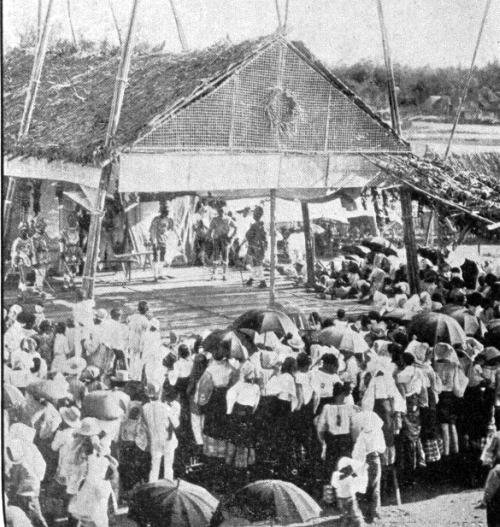

General Bell ordered the entire population of the provinces of Batangas and Laguna to gather into small areas within the poblacion of their respective towns by Dec. 25, 1901. Barrio families had to bring clothes, food, and everything they could carry into the designated area. Everything left behind, houses, gardens, carts, poultry and animals, were burned by the U.S. Army. People found outside the concentration camps were shot.

Starvation and disease took the lives of thousands. Between January and April of 1902, there were 8,350 deaths out of 298,000. Some camps lost as many as 20% of the population. There was one camp that was two miles by one mile (3.2 by 1.6 km) in area. It was “home” to some 8,000 Filipinos. Men were rounded up for questioning, tortured and summarily executed.

Reverend W. H. Walker received a letter from his son and showed it to the Boston Journal, which reported about it on May 5, 1902. The letter described how 1,300 prisoners were executed over a few weeks. A Filipino priest heard their confessions for several days and then he was hanged in front of them. Twenty prisoners at a time were made to dig their mass graves and then were shot. The young Walker wrote, To keep them prisoners would necessitate the placing of the soldiers on short rations if not starving them. There was nothing to do but kill them.

When an American was “murdered” in Batangas, Bell ordered his men to “by lot select a POW—preferably one from the village in which the assassination took place—and execute him.”

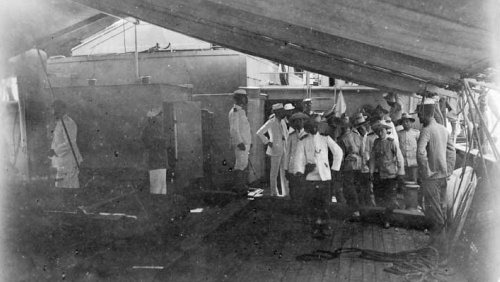

He also rounded up the wealthy and influential residents of Batangas (ABOVE). They were packed like sardines in small rooms, measuring 15-by-30-by-6 feet, into which up to 50 of them were crammed for months. They were pressed into work gangs to burn their own homes, until they agreed to aid American forces.

Bell said, “It is an inevitable consequence of war that the innocent must generally suffer with the guilty”. He reasoned that since all natives were treacherous, it was impossible to recognize “the actively bad from only the passively so.”

Some estimates of civilian deaths on Luzon are as high as 100,000. Many of Malvar’s officers and men gave up and collaborated with the Americans. Malvar realized that continuing the war would harm the people more.

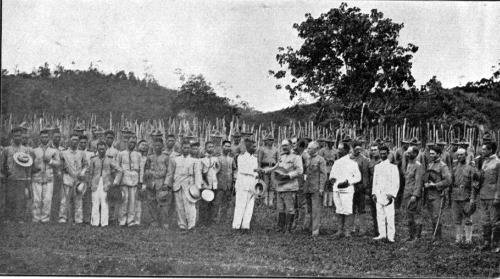

On April 16, 1902, Malvar and his entire command surrendered to the Americans, who treated him honorably. General Bell reported that during the campaign against Malvar, US forces secured 3,561 guns and 625 revolvers, captured, or forced to surrender some eight or ten thousand “insurgents”.

After a few months in the Philippines, Bell was promoted from Captain to Brigadier General, outranking many officers previously his senior. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions of Sept. 9, 1899 near Porac, Pampanga Province.

In 1903, General Bell assisted Secretary of War Elihu Root in developing the overall plan for the reorganization of the US Armys educational system. He was then designated Commandant of the Infantry and Cavalry school, the Signal School, and the Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. As Commandant from 1903 to 1906, he implemented the reorganization plans and became known as the founder of the modern method of instruction in the US Army.

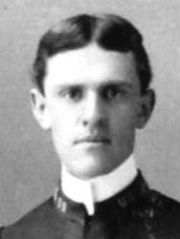

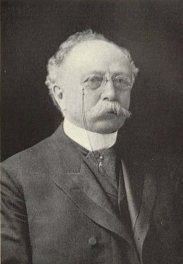

From April 1906 to April 1910 Bell served as Chief of Staff, US Army, with rank of Major General from June 1907 (LEFT).

E. Polk Johnson, author of “History of Kentucky and Kentuckians”, published in 1912, wrote of Bell, “…his frank, open nature and sunny, warm-hearted, generous disposition have won to him a host of friends, both in the army and out of it. To such friends and to this numerous kindred and ‘cousins’ throughout Kentucky, his official title and trappings are of far less moment than his own loyal, lovable, big-hearted manhood, and with these, his own home people, he is even to this day simply but affectionately plain ‘Frank Bell'”.

Bell died in New York City on Jan. 8, 1919 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Sarah Buford Bell (1857-1943) is buried with him.

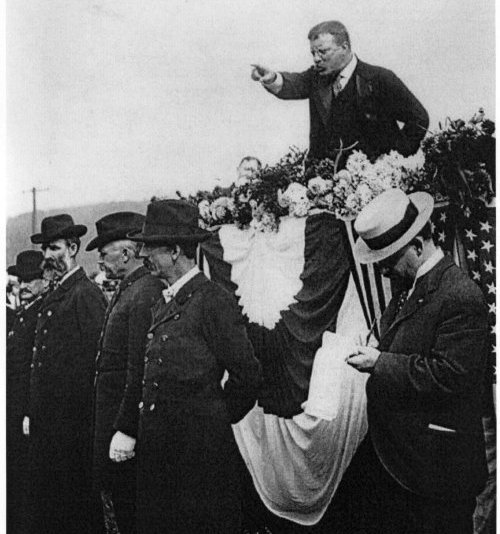

May 30, 1902: President Theodore Roosevelt’s Memorial Day comments on American atrocities

In his “indignant” speech, Roosevelt defended the U. S. Army against charges of “cruelty” in the ongoing Philippine-American War by racializing the conflict as one being fought between the forces of “civilization” and “savagery.” He dismissed the Filipinos as “Chinese half-breeds,” and insisted “this is the most glorious war in our nation’s history.”

In the same year, Albert Gardner, in Troop B of the 1st U.S. Cavalry, composed a would-be comic song dedicated to “water-cure” torture, sung to the tune of the Battle Hymn of the Republic:

“1st

Get the good old syringe boys and fill it to the brim

Weve caught another nigger and well operate on him

Let someone take the handle who can work it with a vim

Shouting the battle cry of freedom

Chorus

Hurrah Hurrah We bring the Jubilee

Hurrah Hurrah The flag that makes him free

Shove in the nozzel deep and let him taste of liberty

Shouting the battle cry of freedom”

President Roosevelt privately assured a friend the water cure was “an old Filipino method of mild torture” and claimed when Americans administered it “nobody was seriously damaged.”

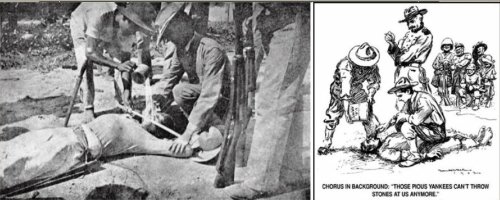

The “treatment” consisted of spread-eagling a prisoner on his back, forcing his mouth open with a bamboo stick and pouring gallons of water down his throat. Helpless, the prisoner was pumped with water until his stomach was near the bursting point. Then he was questioned. If he refused to answer, an American soldier stood or kneeled on his belly, forcing the water out. One report by a U.S. soldier told how “a good heavy man” jumped on a prisoners belly “sending a gush of water from his mouth into the air as high as six feet.”

This cure was repeated until the prisoner talked or died. Roughly half the Filipinos given the cure did not survive. How many Filipinos were killed by torture is not known, but the extent of the practice is documented by a letter sent home by a soldier who bragged of inflicting the water cure on 160 Filipinos, 134 of whom died. A Harvard-educated officer, 1st Lt. Grover Flint, testified before the US Senate on the routine torture of Filipino combatants and civilians. He described the water cure as standard US Army torture.

July 4, 1902: President Theodore Roosevelt declares official end of Philippine “Insurrection”

“Whereas, many of the inhabitants of the Philippine Archipelago were in insurrection against the authority and sovereignty of the Kingdom of Spain at diverse times from August, eighteen hundred and ninety-six, until the cession of the archipelago by that Kingdom to the United States of America, and since such cession many of the persons so engaged in insurrection have until recently resisted the authority and sovereignty of the United States; and

Whereas, the insurrection against the authority and sovereignty of the United States is now at an end, and peace has been established in all parts of the archipelago except in the country inhabited by the Moro tribes, to which this proclamation does not apply; and

Whereas, during the course of the insurrection against the Kingdom of Spain and against the Government of the United States, persons engaged therein, or those in sympathy with and abetting them, committed many acts in violation of the laws of civilized warfare, but it is believed that such acts were generally committed in ignorance of those laws, and under orders issued by the civil or insurrectionary leaders; and

Whereas, it is deemed to be wise and humane, in accordance with the beneficent purposes of the Government of the United States towards the Filipino people, and conducive to peace, order, and loyalty among them, that the doers of such acts who have not already suffered punishment shall not be held criminally responsible, but shall be relieved from punishment for participation in these insurrections , and for unlawful acts committed during the course thereof, by a general amnesty and pardon:

Now, therefore, be it known that I, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, by virtue of the power and authority vested in me by the Constitution, do hereby proclaim and declare, without reservation or condition, except as hereinafter provided, a full and complete pardon and amnesty to all persons in the Philippine Archipelago who have participated in the insurrections aforesaid, or who have given aid and comfort to persons participating in said insurrections , for the offenses of treason or sedition and for all offenses political in their character committed in the course of such insurrections pursuant to orders issued by the civil or military insurrectionary authorities, or which grew out of internal political feuds or dissension between Filipinos and Spaniards or the Spanish authorities, or which resulted from internal political feuds or dissension among the Filipinos themselves, during either of said insurrections :

Provided, however, That the pardon and amnesty hereby granted shall not include such persons committing crimes since May first, nineteen hundred and two, in any province of the archipelago in which at the time civil government was established, nor shall it include such persons as have been heretofore finally convicted of the crimes of murder, rape, arson, or robbery by any military or civil tribunal organized under the authority of Spain, or of the United States of America, but special application may be made to the proper authority for pardon by any person belonging to the exempted classes, and such clemency as is consistent with humanity and justice will be liberally extended; and

Further provided, That this amnesty and pardon shall not affect the title or right of the Government of the United States, or that of the Philippine Islands, to any property or property rights heretofore used or appropriated by the military or civil authorities of the Government of the United States, or that of the Philippine Islands, organized under authority of the United States, by way of confiscation or otherwise;

Provided further, That every person who shall seek to avail himself of this proclamation shall take and subscribe the following oath before any authority in the Philippine Archipelago authorized to administer oaths, namely:

‘I, ________________ , solemnly swear (or affirm) that I recognize and accept the supreme authority of the United States of America in the Philippine Islands and will maintain true faith and allegiance thereto; that I impose upon myself this obligation voluntarily, without mental reservation or purpose of evasion. So help me God.’

Given under my hand at the City of Washington this fourth day of July in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and two, and in the one hundred and twenty-seventh year of the Independence of the United States.”

July 6, 1902: Aguinaldo Is Given Liberty, But Fears Assassination

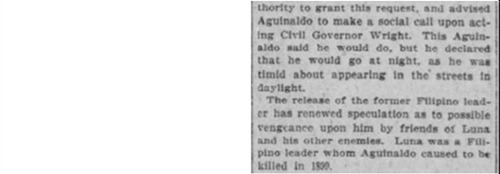

March 27, 1903: General Luciano San Miguel dies in battle

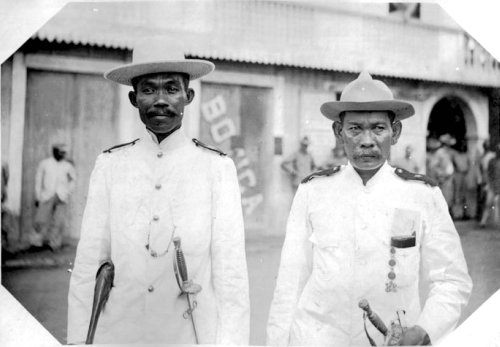

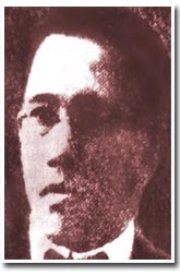

San Miguel (RIGHT, photo from www.nhi.gov.ph) was born on Jan. 7, 1875 in Noveleta, Cavite Province. He joined the Katipunan in 1896 and was a colonel when the war with the Americans broke out on Feb. 4, 1899. He rose to General and saw action in central and western Luzon. He did not surrender or take the oath of allegiance to the United States.

In September 1902, he revived the Katipunan and continued to fight the guerrilla war in Bulacan and Rizal provinces. The American authorities considered San Miguel as the most serious menace to the peace of the Philippines in the years 1902 and 1903.

On Oct. 1, 1902, at a meeting of guerilla leaders presided over by General Benito Santa Ana, San Miguel was elected Supreme Commander of all existing resistance forces, following his great activity in the wilder parts of the provinces of Bulacan and Rizal. On several occasions he had surprised and destroyed detachments of the Philippine Constabulary, and his force had grown to a well-disciplined, well-armed army.

The other resistance leaders present during the meeting were: Laureano Abelino, Severo Alcantara, Anatalio Austria, Miguel Capistrano, Perfecto Dizon, Gregorio Esteban, Ismael Francisco, Carlos Gabriel, Francisco Rivera, Apolonio Samson, Marcelo Santa Ana and Julian Santos.

In Bulacan, in January 1903, San Miguel attacked the command of Capt. William W. Warren, and later, in February 1903, the company of Lt. G.R. Twilley. On both occasions, the Constabulary had been soundly whipped.

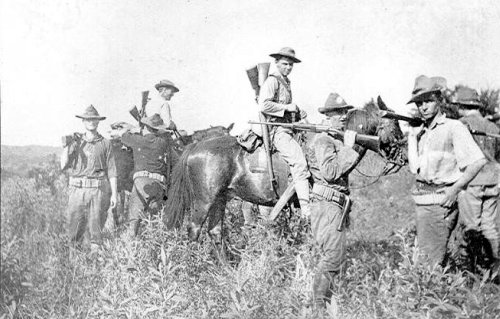

The month of February 1903 found every available Constabulary soldier in the Bulacan-Rizal area in the field in an attempt to locate San Miguel and destroy his force. Flying columns of Scouts and Constabulary, each one company strong, were dispatched with orders to contact his army and co-operate in massed attack upon his positions.

On March 27, 1903, at Corral-na-Bato, Marikina, Rizal Province, General San Miguel’s camp was surrounded and attacked by the First and Fourth Companies of the Philippine Scouts led by First Lieutenants Boss Reese and Frank Nickerson; San Miguel and 34 of his men were killed while the Scouts suffered 3 dead.

General San Miguel was respected by the army and Constabulary officers who pursued him. In 1938, Capt. Cary Crockett (LEFT) —who clashed with General San Miguel in Boso-Boso in February 1903—spoke of him as a brave man and an efficient soldier.

Vic Hurley, the aurhor of “Jungle Patrol: The Story of the Philippine Constabulary” (published 1938), wrote:

“With the passing of San Miguel, the final heartbeat of the Philippine Insurrection sounded. His death was followed by the surrender of many minor leaders, and never again was the United States to encounter resistance from any legitimate leader. San Miguel must be rated a sincere insurgent and not a bandit. The leaders who followed him were bandits.”

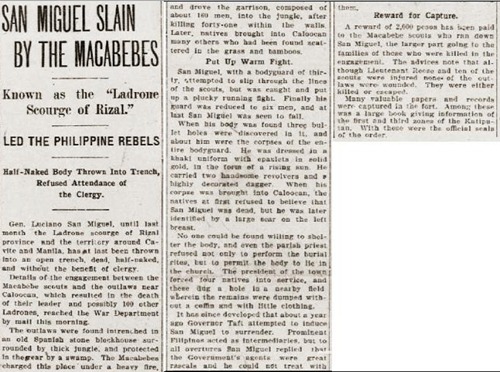

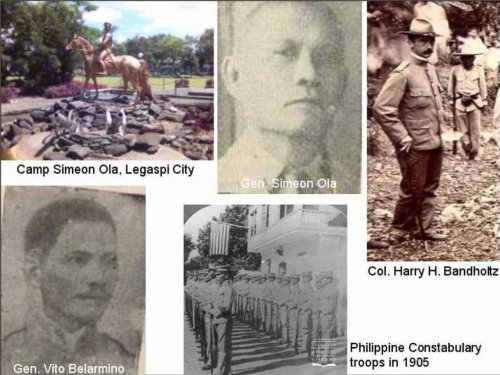

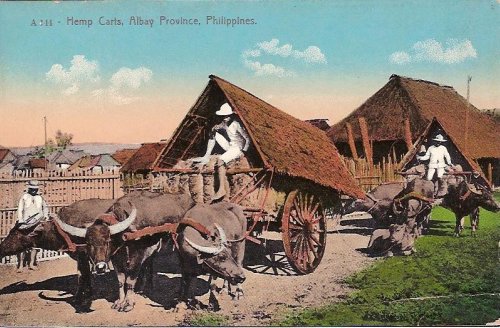

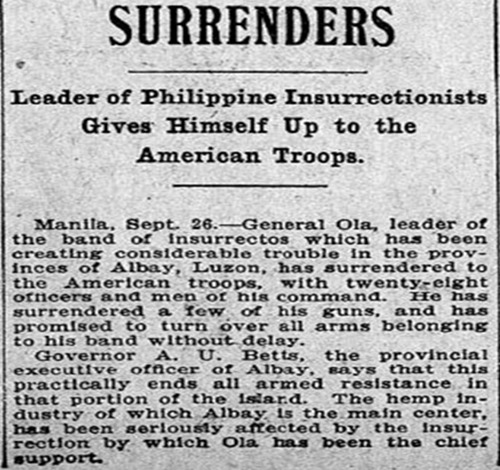

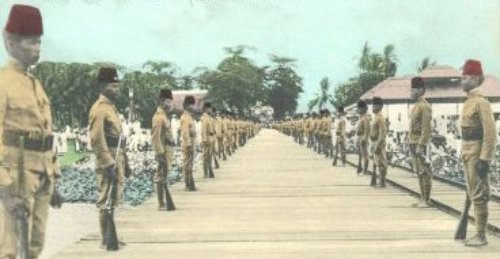

September 25, 1903: General Simeon A. Ola surrenders in Albay

Simeon Ola, a native of Guinobatan, Albay Province, was the last Filipino general to surrender to the Americans, although the latter classified him as a bandit leader, as they did other Filipinos who continued resisting after the US declared the Filipino-American war officially over on July 4, 1902.

On Sept. 22, 1898, less than 5 months before the outbreak of the Fil-Am war on Feb. 4, 1899, the provincial revolutionary government of Albay was formed, with Anaceto Solano as provincial president. Maj. Gen. Vito Belarmino, appointed military commander, reorganized the Filipino army in the province, with Ola serving as a Major.

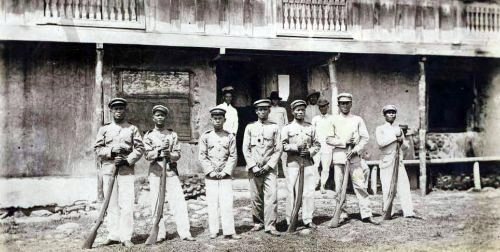

The Americans set up a civil government in Albay on April 22, 1901, and Belarmino surrendered on July 4 of the same year. But Ola, with a thousand men, continued to defy American authority. He launched guerrilla raids on towns garrisoned by combined Philippine Constabulary, Philippine Scouts, and elements of the US Army.

Ola’s attacks in Albay caused an estimated $6,000,000 losses for the US-controlled hemp industry. Col. Harry H. Bandholtz, CO of the Philippine Constabulary in the Bicol region, employed 12 companies of Scout soldiers and an equal number of Constabulary against Ola.

Ola finally surrendered on Sept. 25, 1903 along with about 1,500 men. He showed Bandholtz an electric light bulb; it served as his personal “anting-anting” (amulet). He explained its virtues as follows: “It has always been a sure warning of the presence of American troops near by. When I grasp it in my hand and the wires tremble, I know that the Americans are very near.” Bandholtz jokingly offered the suggestion that the hand trembled to shake the wires because the Americans were near.

Ola (RIGHT) became the first mayor of Guinobatan, serving for 2 consecutive terms.

Camp Simeon Ola (formerly Camp Ibalon), Philippine National Police Regional Office V headquarters in Legaspi City, was named after the Bicolano General on June 24, 1991. Camp Ibalon was called Regan Barracks when it was set up by US army soldiers under Brig. Gen. William Kobbe on Jan. 23, 1900. The Philippine Constabulary, organized in 1901, later took over the camp.

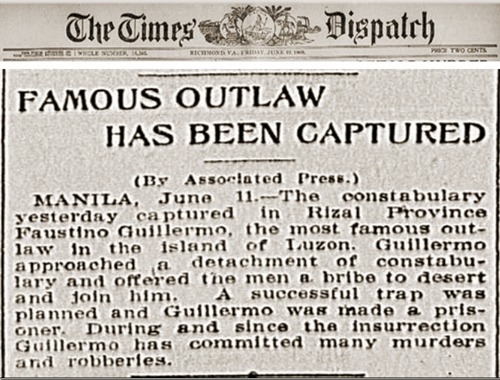

May 20, 1904: Colonel Faustino Guillermo is hanged

Faustino Guillermo was born in 1860 in Sampaloc, Manila. As a Katipunero, he fought alongside Andres Bonifacio. He surrendered to the Americans at Malabon in 1900. Shortly after taking the oath of allegiance to the United States, he established himself at San Francisco del Monte, Morong Province (renamed “Rizal Province” in 1901) and began recruiting men to continue the resistance against American rule. Guillermo was arrested there in 1901 by the Filipino police of Sampaloc. After three months’ imprisonment, he was freed by Lieutenant Lucien Sweet of the municipal secret police, who appointed him as a police informer.

Upon his release, Guillermo returned to San Francisco del Monte and resumed recruitment work for the resistance. He was re-arrested by the Philippine Constabulary (PC) and placed under the custody of Inspector Licerio Geronimo in San Mateo, Rizal Province.(Geronimo commanded the Filipino troops that killed Maj. Gen. Henry W. Lawton at the Battle of San Mateo on Dec. 19, 1899; he surrendered to the Americans on March 30, 1901; he was among a handful of Filipinos admitted into the officer ranks of the colonial Philippine Constabulary).

He went to the mountains and commenced to recruit men, inviting his friends and acquaintances to join him in fighting the Americans. They wandered about the woods, going from Rizal to Bulacan and vice versa, living upon food given them by the people of the barrios.

In early 1902, he joined the forces of General Luciano San Miguel who gave him the rank of Lieutenant Colonel (promoted to Colonel in January 1903). They operated in the provinces of Rizal and Bulacan. Guillermo figured in at least 15 skirmishes with the Philippine Constabulary and Philippine Scouts.

He permitted spies to penetrate his camps. However, before the infiltrators got the chance to report to their American bosses, he unmasked and buried them up to their necks, their heads and faces exposed to the painful bites of huge red ants (hamtik).

On July 15, 1902, Inspector Licerio Geronimo, who was scouting in the Diliman country with seven men (Diliman is now a part of Quezon City), was surprised in a house where he and his men were resting, by Faustino Guillermo and Apolonio Samson with about 25 men, and narrowly escaped capture, after having one of his men killed and another seriously wounded. Geronimo also lost 3 horses, with their trappings and saddles, his uniform, hat and shoes, and escaped in his undershirt and drawers.

In the evening, Guillermo made good use of Geronimo’s PC outfit. He wore it when he entered the PC garrison of 16 men in San Jose, Bulacan; the unsuspecting garrison commander, a Sergeant Omano, obeyed Guillermo’s order and formed the detachment into arms. At this juncture, Guillermo’s men rushed in and took all the constables prisoners and secured their firearms. One of the constables defected to Guillermo’s band.

On March 27, 1903, at Corral-na-Bato, Marikina, Rizal Province, Guillermo and General San Miguel were surrounded and attacked by the First and Fourth Companies of the Philippine Scouts led by First Lieutenants Boss Reese and Frank Nickerson; San Miguel and 34 of his men were killed while the Scouts suffered 3 dead. Guillermo and other survivors escaped to Mt. Laniting, near Boso-Boso (now a sitio of Barangay San Jose, Antipolo City).

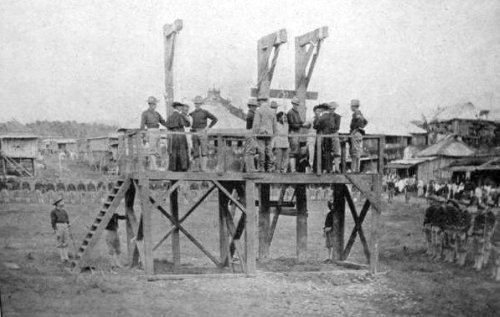

On June 10, 1903 Colonel Guillermo was captured by the Philippine Constabulary. He was charged and convicted of bandolerismo (brigandage). On Oct. 24, 1903, he was sentenced to death by the Court of First Instance of the Province of Rizal.

On May 20, 1904, Colonel Guillermo died at the gallows in Pasig, Rizal. He was 44 years old and a widower.

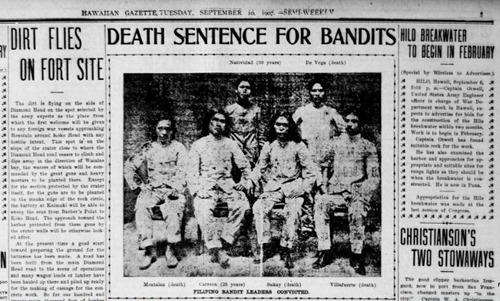

Sept. 13, 1907: Macario Sakay dies at the gallows

Filipino resistance to American rule did not end with the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo on March 23, 1901. There were numerous resistance forces fighting for independence until 1910. One of these forces was led by Macario Sakay who established the “Republika ng Katagalugan” ( literally, “Tagalog Republic”, but by “Katagalugan“, Sakay meant the entire Philippines, and not only the Tagalog-speaking provinces; he and his men were loathed to use “Philippines“, which was named after King Philip of Spain).

He was born on Tabora St. in 1870 in Tondo, Manila, it is presumed, out of wedlock since Sakay was his mother’s family name. He worked as an apprentice in a kalesa (a horse drawn carriage) manufacturing shop and as a tailor.

Sakay also acted in komedyas and moro-moros, which were stage plays named for their depiction of Christian/Muslim conflict. During this time, it can be safely assumed that he met Bonifacio who was also from Tondo and acted in moro-moros as well.

In 1894, Sakay joined the Dapitan, Manila branch of the Katipunan. Sakay fought side by side with Bonifacio in the hills of Morong (now Rizal) Province. Captured by the Americans and amnestied in July 1902, Sakay established the Republika ng Katagalugan in the mountains of Southern Tagalog. He operated in the provinces of Morong, Laguna, Cavite, and Tayabas (now Quezon). His headquarters was first in Mt. Cristobal, Tayabas, and later transferred in the mountains of Morong.

Sakay and many of his followers favored long hair, something strange for his era. This affectation was exploited by the Americans in their efforts to portray Sakay and his men as wild bandits. The Tagalog Republic enjoyed the support of the Filipino masses in Morong, Laguna, Batangas, and Cavite. The Philippine Constabulary continually complained of municipal authorities cooperating and abetting Sakay.

Sakay taxed merchants, farmers, and laborers ten percent of their income. He ordered those who could pay but refused to do so to be arrested and put to work. Suspected informers were liquidated, tortured or had their ears and lips cut off as a warning to others.

The Philippine Constabulary and the U.S. Army employed “hamletting” or reconcentration in areas where Sakay received strong assistance. This cruel counter-insurgency technique proved disastrous for the Filipino masses. The forced movement and reconcentration of a large number of people caused the outbreak of diseases such as cholera and dysentery. Food was scarce in the camps, resulting in numerous deaths.

The Philippine Constabulary relentlessly operated search and destroy missions in an attempt to suppress Sakay’s forces.

On Jan. 31, 1905 the writ of habeas corpus was suspended in the provinces of Cavite and Batangas.

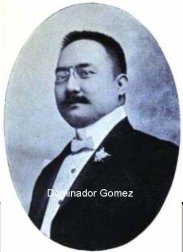

In mid-1906, Governor-General Henry Clay Ide (LEFT) wrote Sakay and promised that if he and his men surrendered, they would be amnestied. The letter was read by Dominador Gomez, a popular labor leader and politician, to Leon Villafuerte, one of Sakay’s generals.

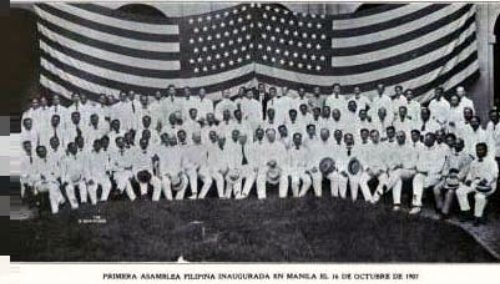

Gomez advised Villafuerte to assure Sakay that a Philippine Assembly comprised of Filipinos will be formed to serve as the “gate of kalayaan.(freedom).” His surrender was necessary to establish a state of peace that was a prerequisite for the election of Filipino delegates to the Philippine Assembly. Gomez acted as the intermediary in the succeeding negotiations.

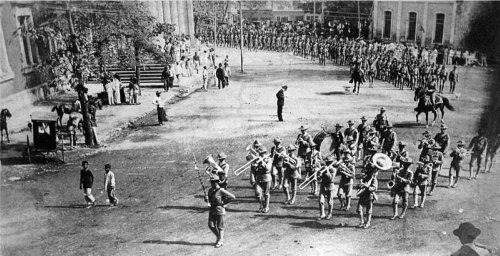

On June 16, 1906 Sakay took the bait, went down to Manila from the hills of Tanay, Morong, and surrendered to Col. Harry H. Bandholtz, Director of the First Constabulary District. Sakay and his men were followed by a brass band and hundreds of townspeople shouting “Long Live Sakay! Long Live the Patriots!”

Sakay viewed his surrender not as capitulation but as a genuine step towards independence. He believed that the struggle had shifted to constitutional methods and that through the Philippine Assembly, the Filipinos could win their independence.

On July 17, 1906, Sakay and his staff attended a dance hosted by Col. Louis J. Van Schaick (LEFT), acting governor of Cavite. Just before midnight, they were arrested.

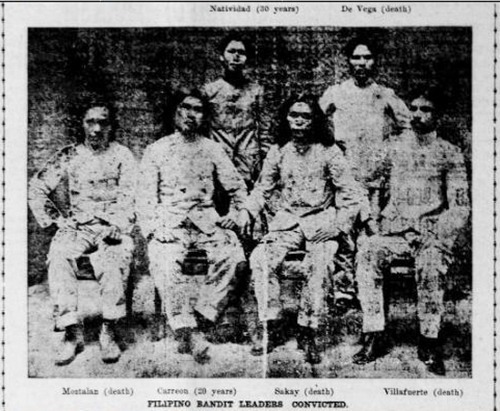

On Aug. 22, 1906 Sakay, Francisco Carreon, Lucio De Vega, Cornelio Felizardo, Julian Montalan and Leon Villafuerte were arraigned in the sala of Judge Ignacio Villamor and accused of bandolerismo under the Brigandage Act of Nov. 12, 1902, which interpreted all acts of armed resistance to American rule as banditry.

During the trial, Dominador Gomez (RIGHT, in 1907) was not around to produce the letter from the American governor-general. He did not even show up and the letter had mysteriously disappeared. (Gomez won a seat in the First Philippine Assembly).

[Ignacio Villamor was born on Feb.1,1863, in Bangued, Abra. He completed his Law Course at the University of Santo Tomas in 1893. In 1898, he represented Ilocos Sur in the Malolos Congress and helped draw up a constitution for the First Philippine Republic. He was a founding member of the pro-American Partido Federal when it was organized on Dec. 23, 1900. Under the American regime, he served as judge, Attorney-General, the first Filipino executive secretary, the first Filipino President of the University of the Philippines (appointed June 7, 1915), and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court (appointed May 19, 1920). He died on May 23, 1933].

On July 26, 1907, the death sentences on Sakay and De Vega were affirmed by the Supreme Court of the Philippines headed by Cayetano S. Arellano.

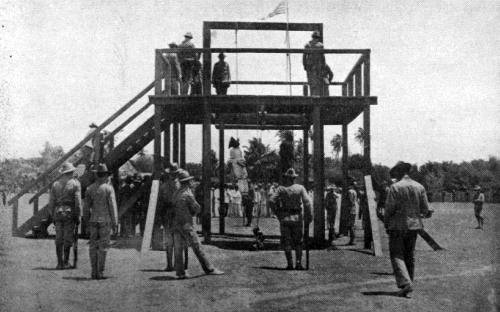

On Friday, 9:00 am, Sept. 13, 1907, at the Bilibid Prison in Manila, Lucio de Vega ascended the scaffold first. “We are members of the revolutionary force that defended our country, the Philippines. We are the true Katipuneros!” He shouted moments before the hangman’s noose was placed around his neck.

He was followed by Macario Sakay who paused briefly and said these parting words:

“Death comes to all of us sooner or later, so I will face the Lord Almighty calmly. But I want to tell you that we were not bandits and robbers, as the Americans have accused us, but members of the revolutionary force that defended our mother country, Filipinas! Farewell! Long live the republic and may our independence be born in the future! Farewell! Long live Filipinas!”

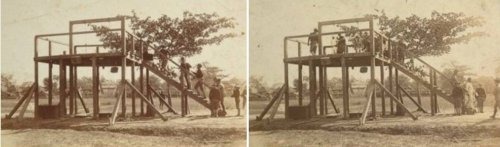

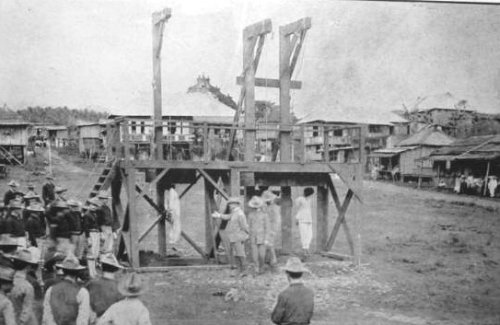

Three “Ladrones” (bandits) are about to be hanged in Tayabas Province (now Quezon). The Brigandage Act of 1902 interpreted all acts of armed resistance to American rule as banditry. PHOTO was taken in the early 1900s.

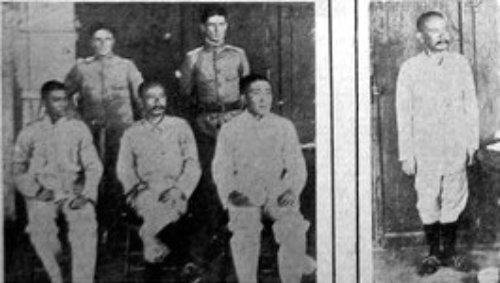

Gen. Artemio “Vibora” Ricarte: He never surrendered

1st commanding general of the Philippine army: March 22, 1897 to Jan 22, 1899. Born on Oct 20, 1866 in Batac, Ilocos Norte. His original surname was Dodon, the Ilocano word for grasshopper.

He graduated from the Colegio de San Juan de Letran with a Bachelor of Arts degree. He took up teaching at the Universidad de Santo Tomas and then at the Escuela Normal de Manila.

He supervised a primary school in San Francisco de Malabon (now General Trias, Cavite). He embraced freemasonry and was made a master mason in September 1896. He joined the Katipunan in Cavite and adopted the name Vibora (viper).

Ricarte (LEFT, in 1898 photo) operated in Cavite, Laguna and Batangas. Aguinaldo ordered him to remain in Biyak na Bato, San Miguel, Bulacan to supervise the surrender of arms and to see to it that the Spanish government complied with the terms of the Biyak na Bato peace pact of Dec. 14, 1897.

Aguinaldo renewed the revolution upon his return from exile in Hong Kong on May 19, 1898.

On June 2, 1898, at San Francisco de Malabon (now General Trias), Cavite Province, Ricarte accepted the surrender of General Leopoldo Garcia Pea, the Spanish commanding general in Cavite, who gave up with 2,800 men.

When the Fil-Am War started on Feb. 4, 1899, he was Chief of Operations of the Filipino forces in the second zone around Manila. In June 1900 he and some of his men sneaked into Manila, intending to organize the populace for an uprising.

On July 1, 1900 Ricarte was arrested at the foot of the Paco bridge. He was confined at the American military headquarters on Anda street in Intramuros, Manila.

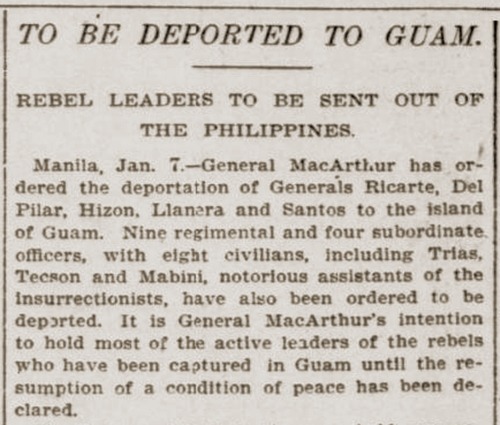

On Jan. 16, 1901, Ricarte was put on the USS Rosecrans and deported to Guam, along with the following 31 military officers and civilians: GENERALS Francisco de los Santos, Pio del Pilar, Maximino Hizon and Mariano Llanera; COLONELS Lucas Camerino, Esteban Consortes, Macario de Ocampo and Julian Gerona; LT. COLONELS Mariano Barroga, Pedro Cubarrubias, Hermogenes Plata and Cornelio Requestis; MAJOR Fabian Villaruel; SUBORDINATE ARMY OFFICERS Igmidio de Jesus, Jose Mata, Alipio Tecson and Juan Leandro Villarino; CIVILIANS Lucino Almeida, Pio Barican, Jose Buenaventura, Anastacio Carmona, Bartolome de la Rosa, Norberto Dimayuga, Doroteo Espina, Silvestre Legaspi, Apolinario Mabini, Juan Mauricio, Pablo Ocampo, Antonio Prisco Reyes, Simon Tecson and Maximino Trias.

[On Jan. 24, 1901, an additional 11 men from Ilocos Norte, described by the Americans as “insurgent abettors, sympathizers and agitators”, were loaded on the USS Solace and also deported to Guam. They were: Faustino Adiarte, Pancracio Adiarte, Florencio Castro, Inocente Cayetano, Gavino Domingo, Pedro Erando, Leon Flores, Jaime Morales, Pancracio Palting, Marcelo Quintos and Roberto Salvante.]

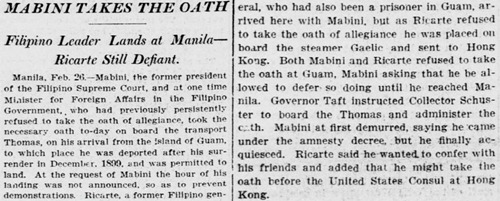

In response to public demand in the US, Ricarte and others were allowed to leave Guam.

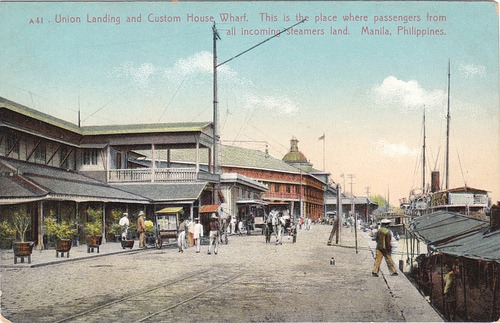

They arrived in Manila on the U.S. transport Thomas on Feb. 26, 1903.

Ricarte was the only one who refused to take the oath of allegiance to the US. He was transported to Hong Kong and there kept under the surveillance of American agents. His mail address in Hong Kong was “U.G. Viper, Esq., Ripon Terrace, Bonham Road”. Jointly with Manuel Ruiz Prin, he established the United Democratic Filipino Republican Committee.

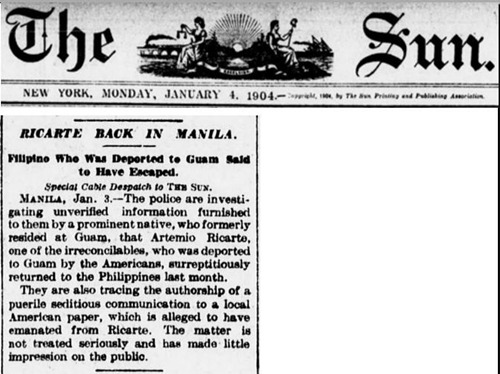

He slipped back to the Philippines on Dec. 25, 1903 hoping to rekindle the Revolution; the Americans offered a reward of $10,000 for information leading to his capture, dead or alive.

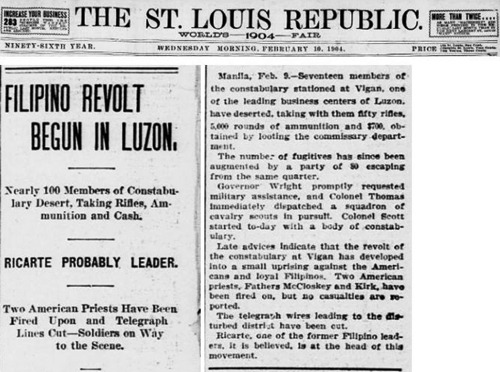

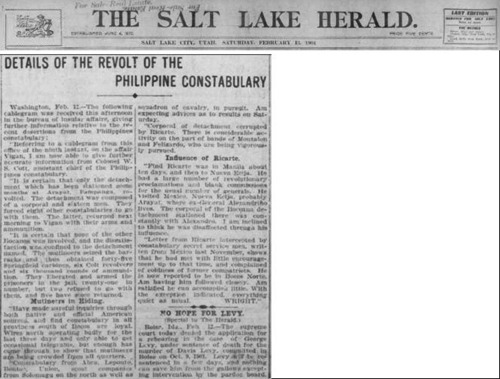

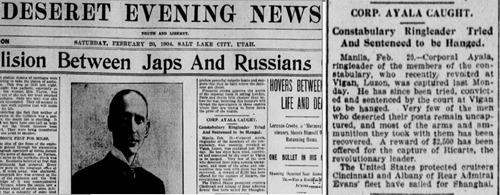

Corporal Carlos Ayala and Second-Class Private Nicolas Calvo of the Philippine Constabulary, while on detached service at Arayat, Pampanga Province, allegedly corresponded with Artemio Ricarte upon his arrival from Hongkong, with the purpose of organizing an insurrection against the colonial government. Upon their return to their home station at Vigan, Ilocos Sur Province, they induced other constables to join, together with a number of residents of the neighboring barrios, in a mutiny.

On the night of Feb. 7, 1904, after supper between 7 and 8 PM, the mutineers went into action. They ransacked the commissary, released the prisoners confined in the provincial jail, tore down the telegraph line, and shot to death fellow constable, Second-Class Private Segundo Bautista, when he refused to cooperate. They went through the streets of Vigan for two hours, firing their guns and cheering for Ricarte and the liberty of the Philippines.

At 9 AM on the following day, more than forty mutineers entered the town of Narvacan. They tore down the American flag from the municipal building, took 28 pesos from the municipal safe, and compelled the town mayor and councilmen to pass a resolution supporting the revolution against the colonial government. At 1 PM of the same day they entered the municipal building at Santa Maria, took 315 pesos from the office of the municipal treasurer, and also compelled the town officials to sign a resolution similar to the one at Narvacan. The same night they entered the town of Santiago, took 350 pesos from the office of the municipal treasurer, and took shelter in the parochial house. They left at 9 AM on the following day,February 9, after forcing town officials to sign a resolution of cooperation.

Constabulary, Scouts, and United States troops of adjoining provinces were sent after the mutineers. By February 15, most of them had surrendered or were captured.

DeathCorporal Carlos Ayala, and Second-Class Privates Macario Agapay and Nicolas Calvo.

Forty years and fine of 10,000 pesosSecond-Class Privates Santiago Asuncion, Doroteo Ayson, Teodoro Edralin, Antonio Guerzon, Cenon Lazo, Maximiano Manganaan, Benito Paez, Modesto Polido, Bruno Propio, Pablo Silvestre, Mariano Vallehermosa, and Anselmo Ygarta.

Ricarte was arrested by the Philippine Constabulary on May 29, 1904 at the cockpit in Mariveles, Bataan Province, where he had gone to meet some co-conspirators. He was then acting as a clerk for a Justice of the Peace under the name of “Jose Garcia”. He was denounced by Luis Baltazar, a clerk of the Court of First Instance in Bataan.

(Araullo was a founding member of the pro-American Partido Federal when it was organized on Dec. 23, 1900. He later served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court from Nov. 1, 1921 until his death on July 26, 1924. Manuel Araullo High School in Manila and Araullo University in Nueva Ecija were named in his honor).

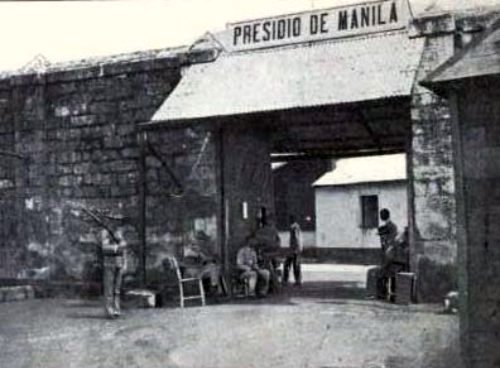

Ricarte served his sentence at the Bilibid Prison in Manila until his release on June 26, 1910. As soon as he stepped out of Bilibid, he was met and detained by several American police agents and brought to the Bureau of Customs. He was asked to swear allegiance to the US; he declined and he was once more deported to Hong Kong.

While in Hong Kong, Ricarte published a magazine entitled “El Grito del Presente” (Cry of the Present).

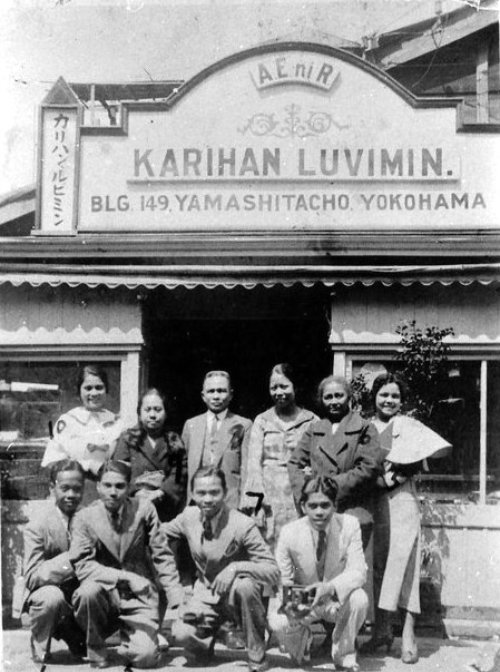

In 1915, during World War I, the British government removed all political exiles from Hong Kong. The Ricartes were shipped to Shanghai and from there, to Japan. They resided in Aichiken, then Tokyo, where Ricarte made his living by teaching Spanish at the Kaigai Shokumin Gakko (Overseas School).

In April 1923, they moved to Yokohama. They lived at 149 Yamashita-cho, Yokohama. Ricarte put up a restaurant whose earnings allowed the family to live in comfort.

At the inauguration of the Philippine Commonwealth on Nov. 15, 1935, the giant Philippine flag, made of Japanese silk, was a gift from General Artemio Ricarte, who was still in exile in Japan. His gift of the Philippine flag was a token of solidarity with his countrymen as they embarked on full autonomy, the penultimate step to independence.

Ricarte collaborated with the Japanese during World War II; on Dec. 21, 1941 they flew him back to the Philippines, via Aparri, Cagayan—he was then 75 years old.

On Feb. 16, 1942, Time Magazine reported: “Old General Artemio Ricarte y Vibora drove proudly about Manila in a sleek limousine, with a spluttering escort of Jap motorcycle guards.”

On Oct 14, 1943, he and Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo raised the Filipino flag during the inauguration of the Japanese-sponsored “Second Philippine Republic”.

Ricarte was not given a high position by the Japanese because of his advanced age. He toured the provinces and promoted cooperation with Japan [RIGHT].

The Americans returned on Oct. 20, 1944, initially smashing Japanese forces on Leyte Island. They proved unstoppable from then on.

In January 1945, when General Tomoyuki Yamashita was preparing to abandon Manila, Japanese officials offered to evacuate him to Japan. Ricarte declined. He said: “I cannot take refuge in Japan at this critical moment when my people are in direct distress. I will stay in my Motherland to the last.”

He fled with Japanese forces under Yamashita into the mountains of northern Luzon.

Without his knowing it, the Japanese executed some 20 of his relatives because the Japanese feared that they knew too much. His own grandson, Besulmino Romero, would have been executed, too, had he not understood what the Japanese were saying and pleaded with them to spare his life,

Ricarte and Yamashita’s army held out in the scenic, highland town of Hungduan, Ifugao Province (then a part of Mountain Province). Ricarte was afflicted with dysentery and with very little to eat, he fell seriously ill and died on July 31, 1945 at the age of 78. He was originally buried on the slopes of Mt. Napulawan. (Yamashita surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945 in Kiangan, Ifugao).

General Ricarte’s remains now lie at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (“Cemetery of Heroes”), Fort Bonifacio, Taguig, Metro Manila.