War Escalates: Battles in Manila and Suburbs, Feb. 5-6, 1899

At daybreak of February 5, the reinforced Americans counterattacked and retook their original positions. Soon after, firing broke out across the 16-mile Filipino and American lines involving 15,000 Filipinos and 14,000 Americans (3,000 of whom were assigned to provost or police duty in Manila). Admiral George Dewey’s navy artillery pounded the Filipino positions.

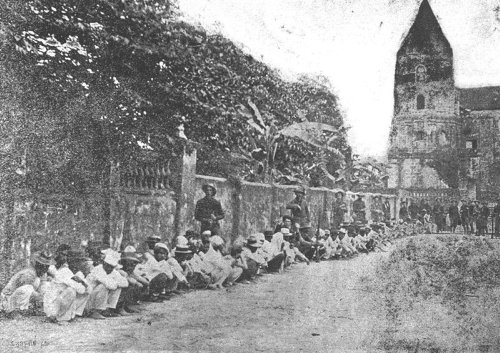

General Hughes sent his Provost Guard out in the streets, blocking off thoroughfares, dispersing crowds, and keeping a close watch on suspected neighborhoods.

Large numbers of suspected “insurgents” were arrested; Hughes grimly noted that “when the police company got through with them the undertaker had enough business for the day.”

Aguinaldo tried to stop the war by sending Gen. Carlos Mario de la Torres to Maj. Gen Elwell S. Otis, commander of the US Eight Army Corps, to propose peace talks and a demilitarized zone. But Otis responded, “fighting, having begun, must go on to the grim end.”

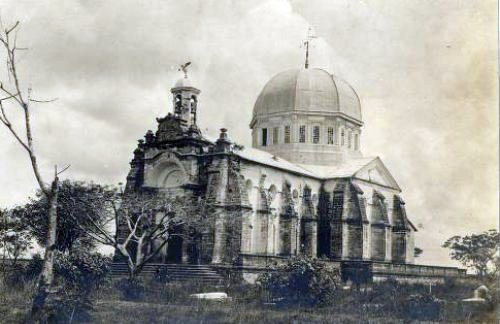

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., commander of the 2nd Division, Eight Corps, attacked the Filipinos in the north and captured La Loma, on the Santa Mesa Ridge overlooking Manila, on February 5. [Santa Mesa Ridge is now known as Santa Mesa Heights in Quezon City]. After capturing the blockhouses, he seized their fortified strongpoints at the Chinese hospital and cemetery and La Loma Church. (La Loma is now a part of Quezon City).

Major Jose Torres Bugallon (RIGHT, image) defended La Loma. He was born on Aug. 28, 1873, in Salasa (now Bugallon), Pangasinan Province. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran in 1889 with high scholastic ratings. In 1892, he went abroad as a pensionado of the Spanish government to the world-famed Academia Militar de Toledo in Spain. He graduated in 1896 and commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 70th Infantry Regiment of the Spanish Army. He fought several battles against Filipino revolutionaries and after the Battle of Talisay on May 30, 1897, he was promoted to Captain. He was also awarded the coveted Cross of Maria Cristina and the Red Cross for Military Honor (Cruz Roja del Merito Militar). After the Treaty of Paris on Dec.10, 1898 ended the Spanish American war, Bugallon joined Gen. Antonio Luna’s staff as aide-de-camp and recruitment officer for Spanish war veterans. At that time, General Luna urgently needed instructors for the training of officers at the Academia Militar in Malolos, Bulacan.

Upon learning from Lt. Colonel Queri, that Bugallon was wounded, General Luna ordered: “He must be saved at all costs. Bugallon is worth 500 Filipino soldiers. He is one of my hopes for future victory.” Too weak to keep his strength any longer due to profuse bleeding, he died on the breast of Gen. Antonio Luna, a few hours after he was withdrawn from the battlefield. General Luna wept unashamedly before the lifeless body of his aide-de-camp. To perpetuate his memory, a law sponsored in 1921 by Congressman Mauro Navarro of Pangasinan changed the name of Salasa to Bugallon. His remains now lie inside the Sampaloc Church in Manila.

The 1st Nebraska Volunteers captured the San Juan Bridge, powder magazine, waterworks, and San Juan del Monte church and convent; the Utah Volunteer Light Artillery occupied Santa Mesa.

Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Anderson, commander of the 1st Division, Eight Corps, routed the Filipinos at Santa Ana, San Pedro de Macati, Guadalupe and the village of Pasay and captured Filipino supplies stored there.

Capt. Albert Otis describes his exploits at Santa Ana in a letter home:

“I have six horses and three carriages in my yard, and enough small plunder for a family of six. The house I had at Santa Ana had five pianos. I couldn’t take them, so I put a big grand piano out of a second-story window. You can guess its finish. Everything is pretty quiet about here now. I expect we will not be kept here very long now. Give my love to all.”

Pvt. Edward D. Furnam, 1st Washington Volunteers, on the battles of February 4th and 5th:

“We burned hundreds of houses and looted hundreds more. Some of the boys made good hauls of jewelry and clothing. Nearly every man has at least two suits of clothing, and our quarters are furnished in style; fine beds with silken drapery, mirrors, chairs, rockers, cushions, pianos, hanging-lamps, rugs, pictures, etc. We have horses and carriages, and bull-carts galore, and enough furniture and other plunder to load a steamer.”

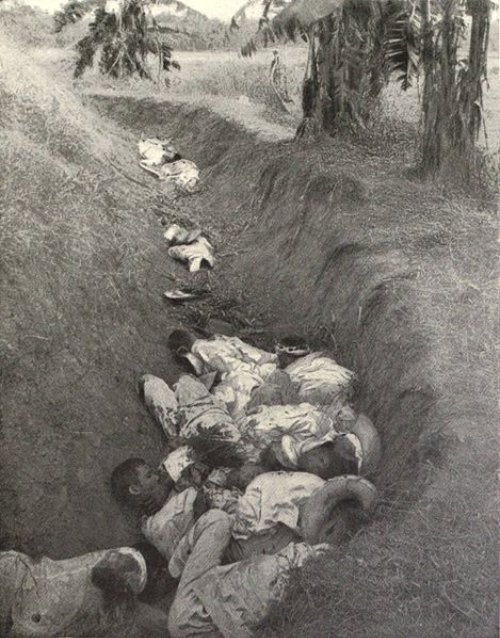

The 1st Idaho and 1st Washington Volunteers massacred hundreds of Filipinos who tried to cross the Pasig River. An American officer estimated that about 700 Filipinos who attempted to cross in boats and by swimming were killed, drowned, wounded or captured. Not a man was seen to have gained the opposite bank. One American soldier explained, “picking off niggers in the water” was “more fun than a turkey shoot.”

The coastlines were pounded continuously by Admiral George Dewey’s naval guns. An English resident commented about Dewey’s role: �This is not war; it is simple massacre and murderous butchery. How can these men resist your ships?� �The Filipinos have swollen heads,� was Dewey’s reply. �They only need one licking and they will go crying to their homes, or we shall drive them into the sea, within the next three days.�

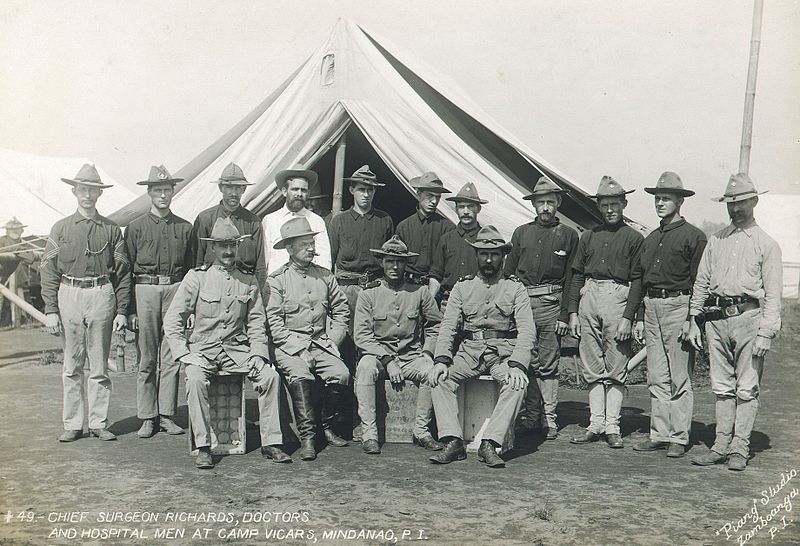

1Lt. Henry Page, Asst. Surgeon, of the Regular Army:

“The recent battle of February 5th was somewhat of a revelation to Americans. They expected the motley horde to run at the firing of the first gun. It was my good fortune to be placed�about ten hours afterward�near the spot where this first gun was fired. I found the Americans still held in check. Our artillery then began to assail the enemy’s position, and it was only by the stoutest kind of fighting that the Tennessee and Nebraska Regiments were able to drive him out… A frequent exclamation along our lines was: ‘Haven’t these little fellows got grit?'”

From Manila, wrote Pvt. Fred B. Hinchman, Company A, United States Engineers:

“At 1:30 o’clock, the general gave me a memorandum with regard to sending out a Tennessee battalion to the line. He tersely put it that ‘they were looking for a fight.’ At Puente Colgante (ABOVE), I met one of our company, who told me that the Fourteenth and Washingtons were driving all before them, and taking no prisoners. This is now our rule of procedure for cause.”

White American troops referred to Filipinos as �niggers,� �Black devils,� and �gugus.� They told friends and relatives that they had come “to blow every nigger to nigger heaven” and vowed to fight “until the niggers are killed off like Indians.”

One white soldier wrote: �Our fighting blood was up, and we all wanted to kill niggers. This shooting human beings beats rabbit hunting all to pieces.”

February 1899: Old woman shot through the leg by US troops while carrying ammunition to the Filipinos. She is shown here being treated by American medics in Manila.

In the 2-day battle of Manila, Harper’s Encyclopaedia of United States History, published in 1901, listed 57 US soldiers killed and 215 wounded; it estimated Filipino dead at 500, with 1,000 wounded and 500 captured. [ Most Filipino historians believe that owing to the heavy firepower unleashed by the Americans, the true number of Filipino dead ranged from 1,000 to 3,000].