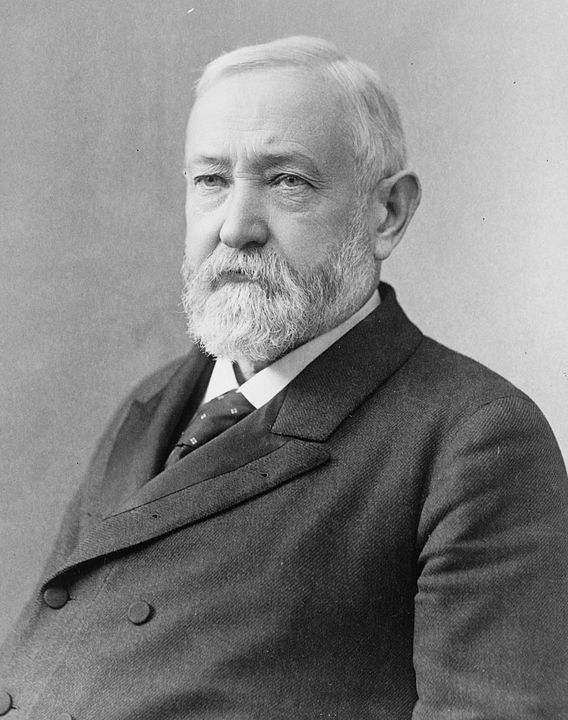

Benjamin Harrison was born to a prominent political family in North Bend, Ohio on August 20, 1833. He was the grandson of the ninth president of the United States, William Henry Harrison to his son, John Scott Harrison. Also, he was the great-grandson of Benjamin Harrison V, also a significant name in American history as one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence. His mother was Elizabeth Ramsey Irwin. Benjamin grew up with four sisters and three brothers.

He was raised on a farm next to his grandfather’s vast estate. Benjamin was only seven years old when his grandfather was elected as the president. Some historical accounts claim that despite being part of a distinguished family, they lived a modest life and his father spent their resources to their education. Growing up, he enjoyed outdoor activities like hunting and fishing; however, he also enjoyed reading in his grandfather’s library.

According to some accounts, Benjamin’s formative education took place in a log cabin; eventually, his parents hired a tutor to prepare him for college. In 1847, Benjamin was only fourteen years old and his brother, Irwin enrolled in Farmer’s College. Soon, he transferred to Miami University in Ohio in 1850. After he graduated, he studied law and passed the bar examination in 1854 they moved to Indianapolis, where he practiced law and even campaigned for the newly formed Republican Party despite his father’s contention to him to enter politics. In 1853, he married Caroline Lavinia Scott, his college sweetheart, and had two children, Russel Benjamin and Mary “Mamie”.

He entered politics and won election as Indianapolis city attorney. He also served as secretary of the Republican State Central Committee and campaigned for the 1860 presidential nominee, Abraham Lincoln, he continued this upward trajectory. Benjamin Harrison, determined to move his career forward, agreed to take on new work while retaining his law practice. He served as the state reporter for the Indiana Supreme Court to this end, summarizing and overseeing the reporting of the official opinions of the court.

The political ambitions of Benjamin Harrison were disrupted by the American Civil War. As a soldier, he joined the Union Army, participating in the Atlanta Campaign of William Tecumseh Sherman. He had achieved the rank of brigadier general by the end of the war.

In 1865, after the war, Benjamin Harrison resumed his law practice, endorsing the Radical Republicans’ Reconstruction policies. In 1876, he struggled to secure the governorship of Indiana, but he was elected to the Senate of the United States in 1881, after many unsuccessful runs for office.

As senator, Harrison stood up against the railroads for the rights of homesteaders and Native Americans, sponsored generous benefits for returning soldiers, and fought for reform of the civil service, such as free Black education and a fairly protective tariff. He was a stout-minded man of kindness who had a sharp intellect and a remarkable memory. With stirring oratory, he could captivate an audience and unhinge his opponents with a cold, discerning eye. He voluntarily sacrificed vital political support on several occasions, instead of abandoning his beliefs. As a result, Benjamin Harrison broke from his party to condemn the infamous 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

In 1885, in his campaign for re-election, Benjamin Harrison was defeated. However, he was not out of the spotlight for long: as the 1888 presidential election approached, after favorite James G. Blaine removed his name from consideration, the Republican Party found itself without a single nominee. On the eighth ballot, he was nominated to run against the incumbent president, Grover Cleveland. The convention chose Levi P. Morton as a running mate.

The campaign focused around the issue of tariffs, with Benjamin Harrison speaking strongly for a strong protective tariff, sound currency, Civil War veterans’ pensions, and office productivity. The bloody shirt history of the Civil War and Reconstruction, which persisted in the American consciousness as an unhealed scar, was a more emotional problem for the electorate.

Benjamin Harrison’s victory relied on New York and Indiana, two swing states. He lost the popular vote by 5,439,853 to Grover Cleveland’s 5,540,309, but won the election by 233 electoral votes to Cleveland’s 168 by outpolling his rival in the Electoral College. The victory of Benjamin Harrison in the Electoral College owed much to his campaign’s lavish spending in the key swing states of New York and Indiana.

He was inaugurated on March 4, 1889. Civil service restructuring, the management of Civil War pensions and the control of tariffs were among the main problems confronting his administration. During Benjamin Harrison’s term, the federal government’s spending policies gave the legislative branch the nickname “the Billion Dollar Congress.”

Benjamin Harrison’s presidency was characterized by an innovative foreign policy and expanding American influence abroad. The First International Conference of American States, held in Washington, D.C., was presided over by its Secretary of State, James G. Blaine, who founded the International Union of American Republics, later referred to as the Pan-American Union, to share cultural and scientific knowledge.

The extension of the nation to include the states of Montana, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming and the Dakotas was one of the enduring legacies of Harrison’s presidency; although Harrison became entangled at the end of his presidency in the Hawaiian annexation debate, the matter remained open in the 1890s.

The Treasury surplus had fade away well before the end of his administration, and prosperity had seemed about to vanish. Congressional elections went stingingly against the Republicans in 1890, and party leaders agreed to leave President Harrison even though he had worked on party legislation with Congress. Nevertheless, he was renominated in 1892 by his party, but Grover Cleveland defeated him for his second, non-consecutive term.

Benjamin Harrison moved to San Francisco, California, where he taught at Stanford University, after leaving his office. He married Mary Lord Dimmick, his late wife’s niece, in 1896. His two adult children disapproved of the marriage of their father to his junior by a relative of 25 years. The couple had a daughter named Elizabeth. He briefly worked as the lead counsel for Venezuela regarding its arbitration of its boundary dispute against Great Britain.

On March 13, 1901, he died at the age of 67 in Indianapolis, Indiana due to pneumonia. His remains were buried in Crown Hill Cemetery beside his two wives.

US Presidents | ||