The Philippines and the United States (U.S.) have a long-standing special relationship that dates back to the late 20th century. For starters, the U.S. has had a hand in liberating the Philippines from its centuries-long colonization by Spain. But, whether the U.S. had deliberately freed the Philippine Independence from the Spanish imperialists out of benevolence or merely took advantage of the political situation is a decades-worth of debate.

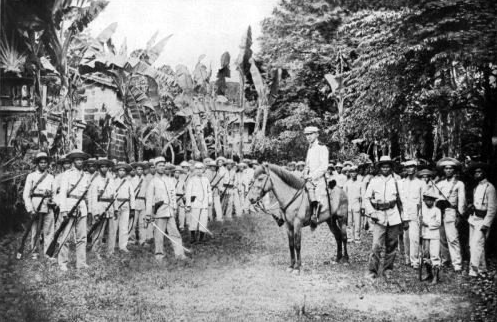

History tells of the tricky, brutal, and bloody fate that transpired in the Philippine islands’ early years of American intervention. After a suspicious and undocumented deal between Emilio Aguinaldo and the American representatives “to fight a common enemy” (Spain), the Filipino revolutionaries didn’t expect the next turn of events. At first, Filipinos believed that this intervention from the friendly Americans would finally set the nation free. But, instead, the U.S. government chose to seize the Philippine Islands for their own. But why?

EXTENSION OF MANIFEST DESTINY

After the Spanish-American War, the American’s seizing of the Philippines accounts for the U.S.’ extension of its manifest destiny – the belief that the nation had a divine duty to expand dominion over the lands and spread democracy. With the collapse of Spain’s long-standing empire, Filipinos assembled military and government institutions, expecting freedom and independence in similar ways to that of Cuba.

When it was apparent that the Americans have other motives for the country, however, the Philippine nationalists were far from pleased. Filipinos asserted their rights to govern the country. But, the Americans saw that as an insurrection – a challenge to their assertion of their divine purpose.

An ugly and brutal war started soon after, in the capital city of Manila, claiming 700 lives from the vanquished Filipino troops and only 44 from the U.S. forces. All of that in just one day on the eve February 4, to the morning, in 1899. The atrocities continued for almost three years as Filipino insurgents continued to stand their ground in what they saw as another nation’s ploy to rule the country.

SECURING A STRATEGIC POST AND ADVANTAGE

The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, ended the U.S.’ war against Spain, and it marked the death of the long reign of the empire. Spain relinquished its control and sovereignty over its colonies, such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, to the United States. However, the fall of the Spanish empire served as an invitation to other nations with similar imperialistic ambitions, particularly Japan and Germany. Moreover, with the political confusion and chaos brought by the power shift in the Philippines, the Americans feared, as history claims, that it might become prey to other foreign entities.

But, that ‘fear’ Americans claimed to have felt for the archipelago was not born of genuine concern. Instead, it was a politically motivated agendum since the Philippines locates in a strategic position in the Pacific. Leaving the Philippines in an ‘unstable’ state could lead other imperialistic powers to take it for themselves, gaining an advantage. So, instead of granting the country independence just like it did Cuba, the U.S. administration deemed it morally justified to seize control of the Philippines, if only temporary.

Regardless of the opposition, the Americans successfully gained dominion over the archipelago, waging war against the disadvantaged Filipino troops and guerilla warriors. From then on, the occupants have built military bases in the country, which came very useful for the Americans in the subsequent wars they fought throughout the Pacific.

ESTABLISH POLITICAL ORDER IN THE PHILIPPINES

The resilience that the Philippine revolutionaries showed in the face of their colonizers was formidable. With 333 years under an oppressive yoke, Filipinos have been waiting and yearning for complete independence all their lives. So, it is not shocking that when the Americans took the Spanish role as colonizers, they felt betrayed and enraged. Regardless, the U.S. government, in the leadership of President William McKinley, was adamant that the Filipino people could not govern themselves without assistance.

U.S. advocates of imperialism insisted that seizing the archipelago was a morally justified cause. The Philippines needed the tremendous American nation to help establish order and educate its people about governance and democracy the American way. President McKinley formed the Schurman Commission, also known as the First Philippine Commission, to investigate the Philippine islands’ conditions on January 10, 1899. The commission found the imminent need for establishing civilian government, bicameral legislature, the autonomous government at both provincial and municipal levels. It also recommended introducing a new school system of free public elementary schools – one of the American’s remarkable contributions to the country.

Consequently, on July 1, 1902, the U.S. Congress enacted the Philippine Organic Act, providing the election of the Philippine Assembly to serve as the lower house of the Philippine legislature, alongside the upper house, which is the Philippine Commission appointed by the president of the U.S. About fourteen years later, the U.S. Congress once again passed an act known as the Jones Act, which will serve as the Philippines’ new organic law. The said act provided for the election of the Philippine Senate and hinted at eventual independence for the country. On March 24, 1934, the Tydings-McDuffie Act granted the Philippines the right to self-governance and autonomy.

World War II and the Japanese invasion from 1941 to 1945 delayed that long-awaited freedom of the Filipino people. But, a year later, the Treaty of Manila was signed between the U.S. and the Philippine government. The treaty finally recognized the latter’s independence and relinquished the former’s sovereignty and control over the archipelago.