The United States entered the 20th century amidst the Filipino-American war that started in 1899. Eventually, the conflict ended with a victory for the U.S., but not without the death of 4,200 American soldiers and over 20,000 Filipino combatants. While those numbers are atrocious, what’s even more abominable is that at least 200,000 civilians died in the end and suffered from the horrors of war. Here, let’s delve deeper into life in the Philippines during the insurrection. Before advanced weapons dominated world wars, there were eras in the past wherein people commonly wore a sword.

Life in the Philippines During the Filipino-American War

During the Filipino-American war, Filipinos weren’t actually solid in their stand against the United States, with some joining the Filipino side to fight for the archipelago’s independence, while others decided to fight for the United States. At that time, an estimated 7.6 million Filipinos were living in the Philippines. About 100,000 fought in the revolution, with tens of thousands more acting as auxiliaries. American soldiers were around 125,000, while approximately 15,000 Filipinos opted to join their side.

Indeed, the largest sector affected by the Filipino-American war were the civilians. While they didn’t have active political participation, they assisted in the war by running errands, hiding and treating soldiers in their homes, and supporting the Filipino revolutionaries with either money or food for the war. Though there were instances, Filipinos were impelled to provide these, most of the time, they had assisted them of their own volition.

Civilians who chose to side with the Americans served as informants, giving the U.S. soldiers valuable information on the whereabouts of the Filipino revolutionaries and food and war supplies. Other civilians threw support to both sides concurrently, with some towns being pragmatically under dual allegiance as they were most likely coerced to support both war efforts. Nevertheless, it never secured them from experiencing the atrocities and destruction of the war.

American troops and witnesses sent letters back home documenting all the violence that the U.S. side did during the war. A Philadelphia Ledger correspondent in Manila described the American forces as 1901 relentless. American soldiers exterminated Filipinos, men, women, and children with the circulating idea that Filipinos were only faintly better than dogs. All captives, prisoners, insurgents, and even suspected ones all met their death.

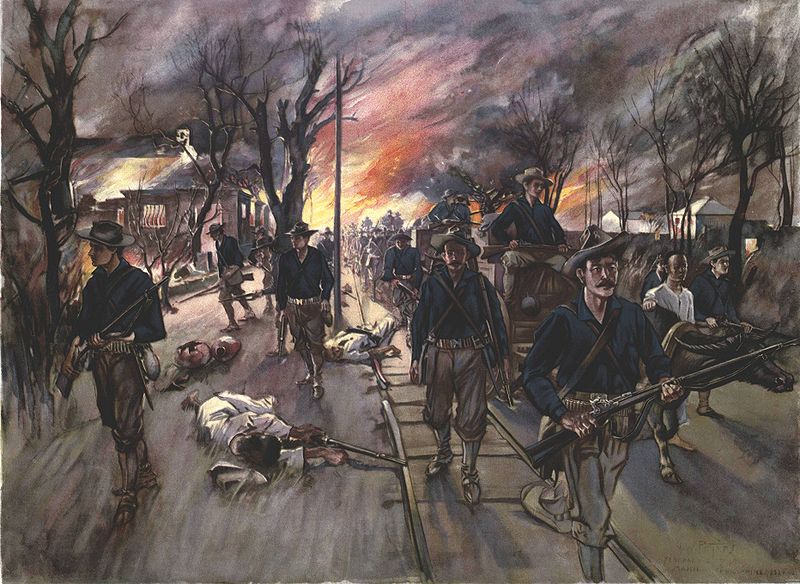

Reports received also chronicled American forces arriving in villages, towns, and cities, ransacking houses and churches and robbing Filipinos of anything of value. Conferring to the U.S. troops through a flag of truce was of no use, as Filipinos holding them were fired upon. Afterward, American soldiers often burned the entire area.

In the 1900 issue of The Alumnus magazine, engineer Theodore Vlademiroff said he had been lucky to witness how villages burned to ashes day and night. Even servicemen had their own writing about these atrocities, citing that towns were being completely wiped out. Others reported American soldiers engaging in wanton action, not even allowing Filipinos to prep for disaster, deliberately wreaking havoc without having any reason to.

In a letter that Corporal Richard O’Brien wrote, he unfolded an incident where his commanding officer instructed them and the soldiers in their company not to take any prisoners. That means simply killing everyone in sight, regardless of sex, gender, or age, making it an apparent massacre. O’Brien implied that such an event was not rare as the soldiers from the other islands in the archipelago had the same conduct. In the end, he surmised that the Filipinos’ hate for the Americans was even larger than what they had for the previous colonizers, the Spaniards.

Yet, Filipino revolutionaries had committed atrocities of their own. According to General Elwell Stephen Otis, Filipinos ruthlessly tortured the American prisoners. He claimed that Americans were executed by burning, bleeding to death, or suffocation. Other reports claimed that Filipino insurgents murdered co-Filipinos and burned down homes and villages just to taint the reputation of the American troops. Thousands of Filipinos, who declined to support Emilio Aguinaldo in the war, were also slaughtered.

Newspaper chronicles cited attacks made by Filipino sharpshooters, deliberately shooting American soldiers, surgeons, and chaplains. In September 1901, on the Island of Samar, a surprise attack by Filipino townspeople enraged by guerillas resulted in the death of nearly fifty American soldiers. The so-called “Balangiga Massacre” triggered retaliation from the U.S. side, killing 2,000-2,500 Filipinos.

Other recounts of Filipinos atrocities suggested that Filipino equaled or even surpassed the brutality committed by the American soldiers. Teodoro Agoncillo, in his book “The History of Filipino People,” said that slapping, kicking, and spitting at faces were some of the common actions done by Filipino insurgents against the prisoners of war. Noses and ears of some American troops were also cut off and were applied with salt afterward.

Indeed, the war became brutal on all sides, with American soldiers and Filipino revolutionaries terrorizing each other, while civilians were suffering amidst the armed conflict. Yet, it wasn’t only from the violence that natives suffered from. The fighting also resulted in agricultural catastrophes, eventual food shortage, famine, and epidemics, such as cholera and malaria, adding to the fear, sorrow, and chaos experienced by the Filipinos in the conflict and making it harder to imagine how life was in the Philippines back then.

On July 4, 1902, the Filipino-American war officially ended. Though some minor skirmishes still followed in the succeeding years. In 1907, the United States shifted the control to the Philippines, which assembled its first assembly. In 1916, the United States Congress passed the Jones Law, which promised eventual independence to the Filipinos, as long as they could prove that they could govern themselves. In 1934, the Tydings–McDuffie Act superseded the Jones Law, this time establishing a 10-year transition period, which finally granted the Philippines its independence in 1946.

Today, life in the Philippines is far from what it was over a century ago during the Filipino-American war. The two countries have developed a strong friendship through the years, keeping everything a part of history and now working hand-in-hand in many aspects.