Early Life

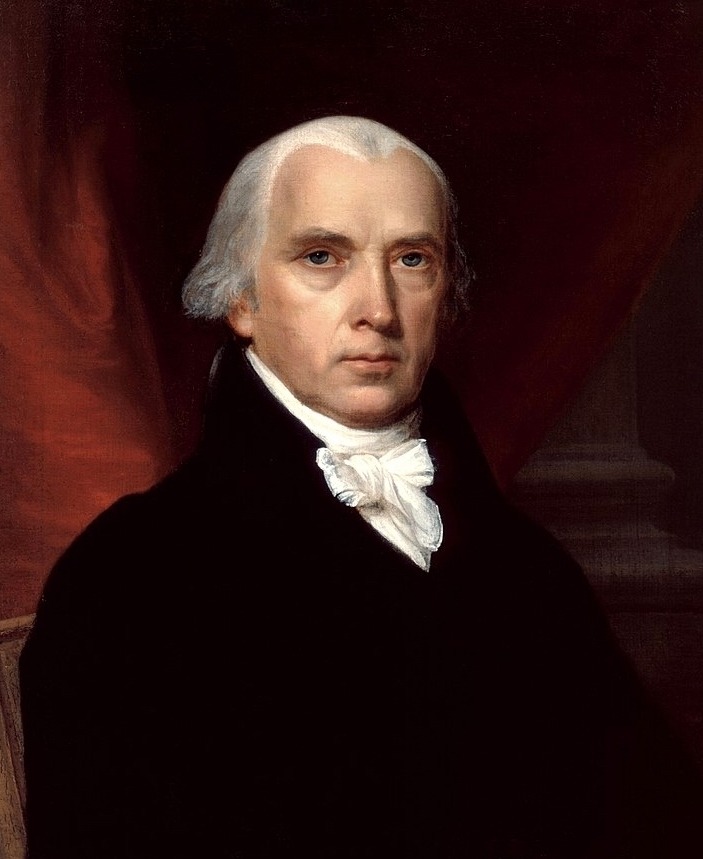

On March 16, 1751, in what is now Port Conway, Virginia, James Madison, Jr. was born. Nellie Conway, his mother, was born in Port Conway and married James Madison, Sr., in 1749. His parents whisked him away to the Madison estate, a slaveholding farm where he would spend the rest of his life. The estate was located in Orange County, Virginia, near the Blue Ridge Mountains’ foothills. Madison was the first of his parents’ twelve children, with just seven surviving childhood.

Madison Sr. was a prominent landowner and squire in Orange County. He was also a vestryman at the neighboring Anglican church of Brick Church. In British colonial Virginia, Anglicanism was the established faith; other Christian denominations and non-Christian religious organizations were not recognized by law, and colonists were expected to pay tithes to support the Anglican Church. Despite being baptized in this church, young James began to criticize organized religion as he grew older, embracing Unitarianism in his religious beliefs.

Madison attended prep school and then the College of New Jersey at Princeton after being educated at home. The young guy excelled in his studies, including Latin and Greek instruction.

Madison was often exposed to the Christian religion and eighteenth-century new thought. John Locke, Isaac Newton, Jonathan Swift, and others were his favorite writers and philosophers. Madison was a founding member of the Princeton debate club, the American Whig Society. During his college years, waves of unrest swept the university as protests against British policy grew louder.

Early Political Activities

Madison’s health deteriorated after graduation, and he was obliged to return home to continue his schooling. Madison served on the Orange County Committee of Safety for two years after her recovery. The American Revolution had erupted by that time, with American armies fighting for freedom from Britain.

He was elected to Virginia’s Revolutionary Convention in 1776, where he crafted the state’s religious freedom guarantee. He helped Thomas Jefferson disestablish the church in the convention-turned-legislature, but he lost reelection by refusing to give free whiskey to the electors.

The war-torn American states were prepared to be loosely controlled by the Articles of Confederation when James Madison entered the Continental Congress in March 1780. The Articles of Confederation were signed in 1777, but they did not take effect until 1781. The concept told them that the thirteen baby states were sovereign entities and that the state governments’ choice might dissolve any national union of which they may be a member. Several men in Congress, including James Madison, resisted such a clear-cut understanding of states’ rights. He perceived fundamental solidarity among the American states that extended well beyond their common opponent, the British.

Madison’s ability earned him a seat in the Continental Congress in 1780, which convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to debate the challenges of British authority. He became one of the leaders of the so-called nationalist group during the first year. The party felt that only a strong central authority could ensure the triumph of the American Revolution. By the time Madison left the army in 1783, the peace deal with Britain had been signed, and the war had come to an end. Madison developed a well-informed and successful leader as one of the half-dozen significant proponents of the bigger national government. Madison spent three years in Virginia, assisting in passing Jefferson’s religious liberty statute and other reform measures.

Madison was rapidly re-involved in politics when he returned to Virginia. In 1784, he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. However, he spent the summer of that year on an extended tour of the northern states before fully immersing himself in legislative activities. He met the Marquis de Lafayette, a famous young Frenchman who had fought alongside General George Washington while on the journey. They traveled together as far as the Mohawk Valley in New York, where Lafayette assisted the Iroquois in resolving a boundary dispute. Madison returned to Virginia in the fall and found himself at differences with Patrick Henry over the state’s religious establishment.

The Father of Constitution and Establishment of the New Government

Madison attended the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in May 1787. Benjamin Franklin and John Adams were among the speakers at the conference, which brought together America’s most influential statesmen. The Constitution, the document that embodies America’s founding ideas, would be drafted at the convention. Madison endorsed the Virginia idea for granting the national government genuine power. He persuaded George Washington and the other Virginia delegates to vote in favor of the scheme. Madison ended up being the most productive member of the conference.

The only thorough chronicle of the events in Madison’s day-by-day notes of the arguments at the Constitutional Convention. To encourage ratification, he worked with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay to publish the Federalist papers in newspapers, of which Madison wrote 29 out of 85, which became the standard constitutional commentary. His influence influenced Virginia’s ratification and contributed to the appointment of John Marshall as Chief Justice of the United States.

Madison devised a plan for the Constitution’s defenders, the Federalists, and contributed to the Federalist Papers, which were works on political theory for the fledgling nation. Madison aided the adoption of the Constitution in June 1788 by engaging in a tense discussion with Senator Patrick Henry. Madison then took the lead in building the new government as Washington’s closest adviser and a member of the first federal House of Representatives. During his first term, he helped Washington draft his inaugural address or first speech as president.

Madison’s and Jefferson’s leadership of the Democratic-Republican party began in January 1790. Madison was opposed to Hamilton’s special treatment of business and riches. Their political party was founded on this philosophy. Madison was also a vocal opponent of Jay’s Treaty, which resolved trade disputes between the United States and the United Kingdom. The pact, Madison believed, would connect the United States with England in a way that would violate the country’s beliefs and norms. As a result, the final approval of Jay’s Treaty signaled Madison’s diminishing power in Congress despite Madison’s vehement opposition. He moved to Virginia a year later.

Madison’s pleasant marriage to Dolley Payne Todd in 1794 alleviated the political difficulties of 1793 to 1800. Dolley, a widow, was a lovely and well-liked woman. Madison would later play a crucial role in shaping the part of the first lady when he was elected president. They also had a great fondness for ice cream as well!

Roles as a president

On March 4, 1809, James Madison was inaugurated as President of the United States. The President-elect arrived at the Capitol with a horse escort and took office on a joyous day. He returned to his home following a brief speech, where he and Dolley welcomed visitors. That evening, at a neighboring hotel, the first-ever Inaugural Ball was held.

Madison persevered in his quest for peace in a war-torn world. Unfortunately, Madison’s position as president would be weakened by failed policies, internal party strife, and Cabinet reorganization. In June 1812, after relations with England deteriorated, war was declared. Many New England pastors and politicians were against the war, and their opposition hindered the war effort and compounded the president’s problems. Despite this, he was comfortably re-elected in 1812.

Madison expected a quick win in the new conflict. Several military losses, however, dashed these ambitions. The tables appeared to be changing as America won victories at sea in 1813. However, the president’s issues grew. Madison was disappointed by the chaos in American finance, troubles with European friends, and another poor military campaign, and he suffered a near-fatal illness in June 1813. The battle seemed to be tearing the new administration apart.

Thousands of battle-hardened British troops arrived on American battlefields in 1814. From a nearby hilltop, Madison observed a tiny but disciplined British army beat the disorganized Americans. His disgrace was total when he witnessed flames from the burning Capitol and White House while escaping across the Potomac River. A peace pact was concluded between Britain and America on Christmas Eve, 1814.

Retirement and Death

Madison left public service in March 1817 and moved to Montpelier, Virginia. Madison spent the following few years practicing scientific agriculture, assisting Jefferson in establishing the University of Virginia, and advising President James Monroe on foreign policy. He only returned to public life in 1829 to participate in the Virginia constitutional convention. But as his health deteriorated, he was forced to become more and more of a silent observer.

Even though he was old and fragile at the time, his mind remained keen, and he continued to remark on politics and write and dictate a large number of letters and notes until his death. On June 28, 1836, that day came when one of his nieces brought him his breakfast, which he could not eat.

Before he died, he penned a message to the nation entitled “Advice to My Country,” sealed it, and instructed that it be opened only after he had passed away. “The council closest to my heart and deepest in my principles is that the Union of the States is treasured and perpetuated,” the telegram stated.

US Presidents | ||