Caloocan City is one of the most urbanized cities in the Philippines, situated at the northern end of Metro Manila. It boasts a vibrant and fast-paced lifestyle, enjoyed by the over 1.6 million people living in its more than 5,000-hectare perimeter. Founded in 1815, the city steadily evolved from a barrio to an advanced and developed city. Exquisite architectural structures and centuries-old monuments exist, reflecting its rich heritage and culture.

Part of its growth also includes being the venue of some of the most notable events in Philippine history, where the brave men and women of Caloocan poured their hearts out and actively participated in the revolution. Here, let’s look back at The Second Battle of Caloocan, one of the most first engagements in the Filipino-American war.

The First Battle

After the culmination of the Battle of Manila, the first skirmish in the Filipino-American War that lasted from February 4-5, 1899, and the Americans won, the Filipino revolutionaries regrouped five days later on February 10 in Caloocan. That commenced the first Battle of Caloocan, where the two forces fought again.

General Antonio Luna commanded the Filipino defenders, while General Arthur MacArthur Jr. led the American offensive. On the said day, the Americans initiated a bombardment of the Filipino-held settlement of Caloocan for three long hours. Following that, a large group of U.S. troops surprised and stormed the city.

Like in the Battle of Manila that took place several days prior, American forces won the engagement, displaying their military superiority over the Filipino troops. It wasn’t a decisive strike, however, as most of the Filipino revolutionaries were able to flee intact. Thus, not causing much positive impact on the American side.

The Preparation

After their plans to reorganize after the Battle of Manila failed with the attack from the Americans, Gen. Luna had to plan again, but this time for a counterattack. His headquarters was moved to Valenzuela City (formerly Polo) and all the operations for the counteroffensive were organized there.

The renowned political philosopher Apolinario Mabini stressed out that plans and preparations must be made thoroughly as the success or failure of the counterattack will spell the future of the Philippine Republic.

Troops under Luna’s helm were divided into three brigades: the West, East, and the Center Brigade. General Pantaleon Garcia led the West Brigade, Colonel Maximino Hizon supervised the East Brigade, while General Mariano Llanera commanded the Center Brigade.

Such division of troops was aligned with General Luna and his army men’s vision of launching a force from the north and south of Manila, with the help of bolo men (sandatahanes) from inside the city. Aside from Luna troops, other reinforcements were men of General Miguel Malvar and General Pio del Pilar from the south and General Licerio Geronimo from the East.

While General Luna asked for the help of battle-tested troops of General Manuel Tinio in Northern Luzon composed of 1,900 men, Luna never received concrete answers from President Emilio Aguinaldo. All in all, the Filipinos accumulated 5,000 soldiers, incredibly outnumbered by the American force consisting of up to 20,000 members in Manila and the nearby provinces.

The Attack

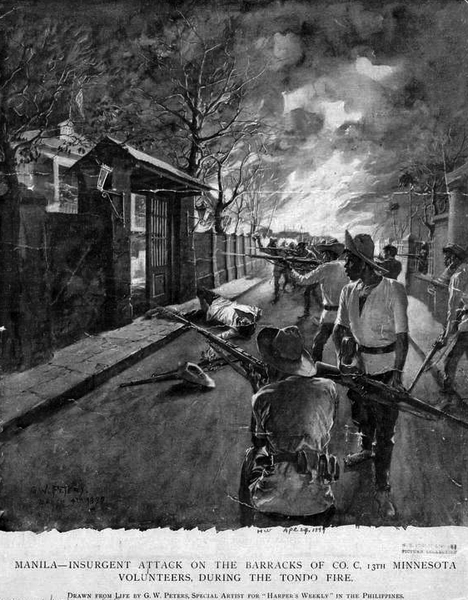

On the night of February 22 at around 9 PM, two fires signaled the beginning of the Filipino counteroffensive. The first was in Santa Cruz, while the second was in Tondo. Both were districts of Manila. Local firefighters didn’t do anything, forcing the Americans to utilize European volunteers and seek support from various infantries to extinguish the fire. As the fire ravaged, Filipino troops started to creep into the city’s northern region. Panic was rampant, with refugees fleeing from the fire.

At around 10 PM, Colonel Francisco Roman and his troops entered Tondo, surprising the American troops. Indecision was certainly present in Americans. The catch is the Filipino revolutionaries experienced confusion themselves.

While Colonel Lucio Lucas quickly responded after getting the cue to attack the American barracks at the Meisic police station, he and his men met a large group of American troops at Azcarraga Street (now Claro M. Recto Avenue).

Initially planning to escape, Lucas saw the houses at their back already engulfed by the flames and rather ordered his troops to attack, deeming it was better to die combating rather than burning into ashes. In the engagement, eight Americans and three Filipinos were killed, with the latter only carrying daggers in their hands.

At the dawn of the following day, the Filipino forces started using cannons to attack the American forces. They then attempted to cross the American line in Caloocan, but the Americans were able to determine their position, firing them with USS Monadnock’s twin turrets. It broke the Filipino offensive and forced them to seek cover.

More problems followed with the lack of coordination between the bolo men and regular Filipino troops. Not to mention that the lack of artillery also posed another setback. One shimmer of hope happened after Gen. Garcia’s troops were able to reach their designated planned locations in Manila. During that time, he even deemed that Manila would soon see the raising of the Philippine flag.

Yet, events turned out the other way. Though Major Canlas and his 400 men from the province of Pampanga made rapid advances and were able to surround La Loma, Quezon City, their ammunition soon ran out. As such, 800 Filipino troops from Kawit, Cavite were tasked to link and help those in La Loma. However, Captain Janolino refused to follow the order, saying he would only follow directives from President Aguinaldo. With that, the Filipinos lost the battle in La Loma.

Still, Filipino forces were able to secure Binondo, Tondo, and Sampaloc by the end of February 23. Meanwhile, Captain Janolino successfully secured Meisic, while Gen. Garcia and Llanera put Caloocan under siege.

On February 24, the Filipino fought harder with the additional reinforcements arriving and supporting the American troops. It was a lost cause as poor discipline and lack of coordination signaled the overall failure and the collapse of the resistance.

The heavy fighting caused 39 casualties on the American side, while a whopping 500 Filipinos died in the battle. General Luna disarmed Janolino’s army due to insubordination, but President Aguinaldo transferred them to Major Ramos’ helm. After hearing of the reinstatement, General Luna filed his resignation on February 28.

Though the Filipinos lost the battle and failed to regain Manila, it was only the start as the Filipino-American war didn’t cease until the next three years.