Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal will forever be linked together in history. When he first took office in 1901 (following the assassination of President William McKinley), the Panama Canal project was a recently-abandoned disaster. Started by the French Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interoceanique on February 1, 1881, the project had been funded by more than 100,000 investors who had contributed small amounts. Originally, plans by Ferdinand de Lesseps (who had previously built the Suez Canal) called for a 50-mile canal at sea level, running by the path of the Panama Railroad. His original estimates included a 12 year timeline at a price tag of $132 million. What no one could foresee would lead to misfortune, disgrace, and colossal financial loss.

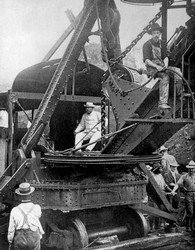

After cutting a pathway through the jungle, digging began on January 20, 1882. With a crew comprised of primarily black and Indian laborers, along with a collection of modern, new equipment like tugboats and steam shovels. At first, there was steady progress, but when the rains started De Lesseps discovered what others had tried to warn him about: Panama’s unforgivable climate (heat and rain), wildlife (mosquitoes and snakes), and disease (malaria, smallpox, and yellow fever). In 1881, there were nearly 60 deaths from disease alone. By 1882, there were twice that many. When the French attempt finally ended in December 1888, more than $287 million of investors’ money was spent, with only eleven miles of canal and the death of more than 20,000 men.

In 1902, Roosevelt negotiated the rights to the property for $40 million and started negotiations with Colombia for a treaty. Despite foreboding predictions about the success of such a treaty, Teddy joined with those holding business interests in Panama to stage a revolution. Because it was only for show, soldiers willingly surrendered (after being paid $50 each) and Panama became a nation on November 3, 1903. At first, American efforts were unsuccessful, almost an exact repeat of the French failure. Realizing the need for sanitation – and elimination of mosquitoes – Dr. William Gorgas was called in. Previously, he had successfully lead the cleanup of yellow fever in Havana; he conducted similar activities in Panama. Engineering was also changed to the “lake and lock” canal idea, which Roosevelt was a proponent for. This system involved damming the Chagres, creating a lake in the interior of the country. Locks would then raise ships out of the Atlantic to the lake’s level, allowing them to cross to locks on the Pacific side.

Despite more setbacks (including broken equipment, weather, and natural disasters) and another unexpected change of engineers, the Panama Canal was finally completed on September 26, 1913. Nine years after starting their efforts, engineers successfully tested the lock system. The official opening of the Panama Canal took place on August 15, 1914. Unfortunately, with the world immersed in WWI, the completion of one of the most important engineering feats of the 20th century went largely unnoticed.