The War in 1900-1901: African Americans in the Fil-Am War

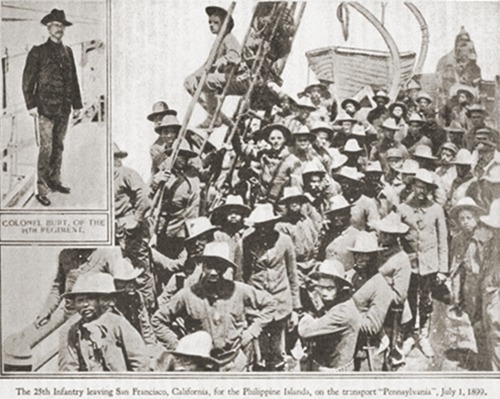

Companies from the segregated Black 24th and 25th infantry regiments reported to the Presidio of San Francisco in early 1899. They arrived in the Philippines on July 30 and Aug. 1, 1899. The 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments were sent to the Philippines as reinforcements, and by late summer of 1899, all four regular Black regiments plus Black national guardsmen had been brought into the war against the Filipino “Insurectos.” The two Black volunteer infantry regiments — 49th and 48th — arrived in Manila on January 2 and 25, 1900, respectively.

The U.S. Army viewed its “Buffalo soldiers” as having an extra advantage in fighting in tropical locations. There was an unfounded belief that African-Americans were immune to tropical diseases. Based on this belief the U.S. congress authorized the raising of ten regiments of “persons possessing immunity to tropical diseases.” These regiments would later be called “Immune Regiments”.

Many Black newspaper articles and leaders supported Filipino independence and felt that it was wrong for the US to subjugate non-whites in the development of a colonial empire. Some Black soldiers expressed their conscientious objection to Black newspapers. Pvt. William Fulbright saw the U.S. conducting “a gigantic scheme of robbery and oppression.” Trooper Robert L. Campbell insisted “these people are right and we are wrong and terribly wrong” and said he would not serve as a soldier because no man “who has any humanity about him at all would desire to fight against such a cause as this.” Black Bishop Henry M. Turner characterized the venture in the Philippines as “an unholy war of conquest”.

Many Black soldiers increasingly felt they were being used in an unjust racial war. One Black private wrote that the white mans prejudice followed the Negro to the Philippines, ten thousand miles from where it originated.

The Filipinos subjected Black soldiers to psychological warfare. Posters and leaflets addressed to “The Colored American Soldier” described the lynching and discrimination against Blacks in the US and discouraged them from being the instrument of their white masters’ ambitions to oppress another “people of color.” Blacks who deserted to the Filipino nationalist cause would be welcomed.

One soldier related a conversation with a young Filipino boy: Why does the American Negro come to fight us where we are a friend to him and have not done anything to him. He is all the same as me and me the same as you. Why dont you fight those people in America who burn Negroes, that make a beast of you?

Another Black soldier, when asked by a white trooper why he had come to the Philippines, replied sarcastically: Why doan know, but I ruther reckon were sent over here to take up de white mans burden.

One of the Black deserters, Private David Fagen of the 24th Infantry, born in Tampa, Florida in 1875, became notorious as “Insurecto Captain”. On Nov. 17, 1899, Fagen, assisted by a Filipino officer who had a horse waiting for him near the company barracks, slipped into the jungle and headed for the Filipinos’ sanctuary at Mount Arayat. The New York Times described him as a cunning and highly skilled guerilla officer who harassed and evaded large conventional American units. From August 30, 1900 to January 17, 1901, he battled eight times with American troops.

Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston put a $600 price on Fagen’s head and passed word the deserter was “entitled to the same treatment as a mad dog.” Posters of him in Tagalog and Spanish appeared in every Nueva Ecija town, but he continued to elude capture.

On Dec. 5, 1901, Anastacio Bartolome, a Tagalog hunter, delivered to American authorities the severed head of a negro he claimed to be Fagen. While traveling with his hunting party, Bartolome reported that he had spied upon Fagen and his Filipina wife accompanied by a group of indigenous people called Aetas bathing in a river.

The hunters attacked the group and allegedly killed and beheaded Fagen, then buried his body near the river. But this story has never been confirmed and there is no record of Bartolome receiving a reward. Official army records of the incident refer to it as the supposed killing of David Fagen, and several months later, Philippine Constabulary reports still made references to occasional sightings of Fagen.

A Black newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, editorialized in December, 1901, “Fagen was a traitor and died a traitor’s death, but he was a man no doubt prompted by honest motives to help a weakened side, and one he felt allied by bonds that bind.”

During the war, 20 U.S. soldiers, 6 of them Black, would defect to Aquinaldo. Two of the deserters, both Black, were hanged by the US Army. They were Privates Edmond Dubose and Lewis Russell, both of the 9th Cavalry, who were executed on Feb. 7, 1902, before a crowd of 3,000 at Guinobatan, Albay Province.

Nevertheless, it was also felt by most African Americans that a good military showing by Black troops in the Philippines would reflect favorably and enhance their cause in the US.

The sentiments of most Black soldiers in the Philippines would be summed up by Commissary Sergeant Middleton W. Saddler of the 25th Infantry, who wrote, “We are now arrayed to meet a common foe, men of our own hue and color. Whether it is right to reduce these people to submission is not a question for soldiers to decide. Our oaths of allegiance know neither race, color, nor nation.”

Although most Blacks were distressed by the color line that had been immediately established in the Philippines and by the epithet “niggers”, which white soldiers applied to Filipinos, they joined whites in calling them “gugus”. A black lieutenant of the 25th Infantry wrote his wife that he had occasionally subjected Filipinos to the water torture.

Capt. William H. Jackson of the 49th Infantry admitted his men identified racially with the Filipinos but grimly noted “all enemies of the U.S. government look alike to us, hence we go on with the killing.”

Jan. 6, 1900: US Newspaper Reports Record Incidence of Insanity Among Americans In The Philippines

Jan. 7, 1900: Battle of Imus, Cavite Province

On Jan. 7, 1900, the 28th Infantry Regiment of US Volunteers, commanded by Col. William E. Birkhimer, engaged a large body of Filipinos at Imus, Cavite Province.

The Americans suffered 8 men wounded, and reported that 245 Filipinos were killed and wounded.

January 14-15, 1900: Battle of Mt. Bimmuaya in Ilocos Sur

On Jan. 14-15, 1900, the only artillery duel of the war was fought in Mount Bimmuaya, a summit 1,000 meters above the Cabugao River, northwest of Cabugao, Ilocos Sur Province. It is a place with an unobstructed view of the coastal plain from Vigan to Laoag. The Americans — from the 33rd Infantry Regiment USV, and the 3rd US Cavalry Regiment — also employed Gatling guns and prevailed mainly because their locations were concealed by their use of smokeless gunpowder so that Filipino aim was wide off the mark.

It was believed that General Manuel Tinio, and his officers Capt. Estanislao Reyes and Capt. Francisco Celedonio were present at this encounter but got away unscathed.

Elements of this same 33rd Infantry unit had killed General Gregorio del Pilar earlier on Dec. 2, 1899, at Tirad Pass, southeast of Candon, llocos Sur.

The Battle of Mt. Bimmuaya diverted and delayed US troops from their chase of President Emilio Aguinaldo as the latter escaped through Abra and the mountain provinces. After the two-day battle, 28 unidentified fighters from Cabugao were found buried in unmarked fresh graves in the camposanto (cemetery).

General Tinio switched to guerilla warfare and harassed the American garrisons in the different towns of the Ilocos for almost 1 years.

January 20, 1900: Americans invade the Bicol Region

In early 1900, during their successful operations in the northern half of Luzon Island, the Americans decided to open the large hemp ports situated in the southeastern Luzon provinces of Sorsogon, Albay and Camarines, all in the Bicol region.

Brig. Gen. William A. Kobbe (ABOVE, in 1900) was relieved from duty on the south Manila line and ordered to seize the desired points. His expeditionary force was composed of the 43rd and 47th Volunteer Infantry Regiments, and Battery G , 3rd Artillery. He sailed on the afternoon of January 18, with the transport Hancock and two coasting vessels, the Castellano and Venus. His command was convoyed by the gunboats Helena and NashviIlle.

On January 20, the Americans entered Sorsogon Bay and took possession, without opposition, of the town of Sorsogon, where Kobbe left a small garrison. They proceeded to the small hemp ports of Bulan and Donsol, at each of which a company of the 43rd Infantry was placed. The expedition then sailed through the San Bernardino Strait to confront the Filipinos at Albay Province.

On January 24, Virac, Catanduanes Island (then a part of Albay Province), was taken by the Americans without a shot being fired.

On February 8, Tabaco, Albay was captured and on February 23, Nueva Caceres (today’s Naga City), Camarines fell.

Paua was the only pure Chinese in the Philippine army.

He was born on April 29, 1872 in a poor village of Lao-na in Fujian province, China.

In 1890, he accompanied his uncle to seek his fortune in the Philippines. He worked as a blacksmith on

Jaboneros Street, Binondo, Manila.

Paua joined the Katipunan in 1896. His knowledge as blacksmith served him in good stead. He repaired native cannons called lantakas and many other kinds of weaponry. He set up an ammunition factory in Imus, Cavite where cartridges were filled up with home-made gunpowder. [On the side, he courted Antonia Jamir, Emilio Aguinaldo’s cousin].

On April 26, 1897, then-Major Paua, Col. Agapito Bonzon and their men attacked and arrested Katipunan Supremo Andres Bonifacio and his brother Procopio in barrio Limbon, Indang, Cavite Province; Andres was shot in the left arm and his other brother, Ciriaco, was killed. Paua jumped and stabbed Andres in the left side of the neck. From Indang, a half-starved and wounded Bonifacio was carried by hammock to Naik, Cavite, which had become Emilio Aguinaldos headquarters. The Bonifacio brothers were executed on May 10, 1897.

Paua (LEFT) was the only foreigner who signed the 1897 Biyak-na-Bato Constitution. He was among 36 Filipino rebel leaders who went in exile to Hong Kong by virtue of the Dec. 14, 1897 Peace Pact of Biyak-na-bato.

Emilio Aguinaldo and the other exiles returned to Manila on May 19, 1898. The revolution against Spain entered its second phase.

On June 12, 1898, when Aguinaldo proclaimed Philippine independence in Kawit, Cavite, Paua cut off his queue (braid). When General Pantaleon Garcia and his other comrades teased him about it, Paua said: “Now that you are free from your foreign master, I am also freed from my queue.”

[The queue, for the Chinese, is a sign of humiliation and subjugation because it was imposed on them by the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty. The Chinese revolutionaries in China cut off their queues only in 1911 when they finally toppled the Manchu government.] For more information on the Qing Dynasty, check out our article, Learn About the Rise and Fall of the Qing Dynasty, One of the Largest Dynasties of Imperial China.

On Oct. 29, 1898, Paua was included in the force led by General Vito Belarmino that was sent to the Bicol region; Belarmino assumed the position of military commander of the provinces of Albay, Camarines and Sorsogon.

Paua married Carolina Imperial, a native of Albay; he retired in Albay and was once elected town mayor of Manito. He told his wife and children: I want to live long enough to see the independence of our beloved country and to behold the Filipino flag fly proudly and alone in our skies.

His dream was not realized because he died of cancer in Manila on May 24, 1926 at the age of 54.

February 5, 1900: Ambush at Hermosa, Bataan Province

On Feb. 5, 1900, a supply train of Company G, 32nd Infantry Regiment of U.S. Volunteers, was ambushed near Hermosa, Bataan Province. The 11-man detail was commanded by Sgt. Clarence D. Wallace. It was sent from Dinalupihan by the Company Commander, Capt. Frank M. Rumbold, to escort Capt. William H. Cook, regimental assistant surgeon, to Orani. On arrival, the soldiers would report to the commissary officer for rations, which they were to escort back to Dinalupihan. It was while on their return trip that the party was ambushed; 6 Americans were killed. It was one of the deadliest ambuscades of U.S. troops in the war.

Forty-eight hours before this occurrence, detachments of the 32nd Infantry Regiment scouted the country south of Orani, west to Bagac, north to Dinalupihan, and west to Olongapo, without finding any trace of Filipino guerillas. Following the ambush, all American units in the province were directed to exercise extraordinary vigilance on escort and similar duty.

The regiment, commanded by Col. Louis A. Craig, was based in Balanga, Bataan Province. It posted companies of troops in Abucay, Balanga, Dinalupihan, Mariveles, Orani and Orion, and the towns of Floridablanca and Porac in neighboring Pampanga Province.

The ambush is reported on The Tribune, Manila, issue of Feb. 8, 1900.

Execution of Filipinos, circa 1900-1901

War in Bohol, March 17, 1900 – Dec. 23, 1901

On March 17, 1900, 200 troops of the 1st Battalion, 44th Infantry Regiment of U.S. Volunteers (USV), led by Maj. Harry C. Hale, arrived in Tagbilaran. Bohol was one of the last major islands in the Philippines to be invaded by American troops. Bernabe Reyes, “President” of the “Republic of Bohol” established on June 11, 1899, separate from Emilio Aguinaldo’s national government, did not resist. Major Hale hired and outfitted Pedro Samson to build an insular police force. In late August, he took off and emerged a week later as the island’s leading guerilla.

Company C of the 44th U.S. Volunteers encountered Samson on Aug. 31, 1900 near Carmen. The guerillas were armed with bolos, a few antique muskets and “anting-anting” or amulets. More than 100 guerillas died. The Americans lost only one man.

Two hundred men from the 19th U.S. Regular Infantry Regiment led by Capt. Andrew S. Rowan, West Point Class 1881 (LEFT), reinforced the Americans on Bohol.

On Sept. 3, 1900, they clashed with Pedro Samson in the Chocolate Hills. From then on through December, US troops and guerillas met in a number of engagements in the island’s interior, mostly in the mountains back of Carmen. Samson’s force consisted of Boholanos, Warays from Samar and Leyte, and Ilonggos from Panay Island. They lacked firepower; most of them were armed simply with machetes.

The Americans resorted to torture —most often “water cure”—and a scorched-earth policy: prominent civilians were tortured; 20 of the 35 towns of Bohol were razed, and livestock was butchered wantonly to deprive the guerillas of food.

In May 1901, when a US soldier raped a Filipina, her fiance murdered him. In retaliation, Capt. Andrew S. Rowan torched the town of Jagna. On June 14-15, 1901, US troops clashed with Samson in the plain between Sevilla and Balilihan; Samson escaped, but Sevilla and Balilihan were burned to the ground.

On Nov. 4, 1901, Brig. Gen. Robert Hughes, US commander for the Visayas, landed another 400 men at Loay. Torture and the burning of villages and towns picked up. (At US Senate hearings in 1902, when Brig. Gen. Robert Hughes described the burning of entire towns in Bohol by U.S. troops to Senator Joseph Rawlins as a means of “punishment,” and Rawlins inquired: “But is that within the ordinary rules of civilized warfare?…” General Hughes replied succinctly: “These people are not civilized.”)

At Inabanga, the Americans killed the mayor and water-cured to death the entire local police force. The mayor of Tagbilaran did not escape the water cure. At Loay, the Americans broke the arm of the parish priest and used whiskey, instead of water, when they gave him the “water cure”. Major Edwin F. Glenn, who had personally approved the tortures, was later court-martialed.

On Dec. 23, 1901, at 3:00 pm, Pedro Samson signed an armistice in the convent of Dimiao town. He arrived with 175 guerillas. That night at an army-sponsored fete there were speeches and a dance.

On Feb. 3, 1902, the first American-sponsored elections were held on Bohol and Aniceto Clarin, a wealthy landowner and an American favorite, was voted governor. The Philippine Constabulary assumed the US army’s responsibilities and the last American troops departed in May 1902.

Guerilla Resistance On Mindanao Island, 1900-1902

BATTLE OF CAGAYAN DE MISAMIS, APRIL 7, 1900. When the Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American War on Dec. 10, 1898, the Spanish governor of Misamis Province turned over his authority to two Filipinos appointed by Emilio Aguinaldo: Jose Roa, who became the first Filipino governor of Misamis; and Toribio Chavez, who served as the first Filipino mayor of Cagayan de Misamis (now Cagayan de Oro City). [On Nov. 2, 1929, Misamis Province was divided into Misamis Occidental and Misamis Oriental].

On Jan. 10-11, 1899, Cagayan de Misamis celebrated Philippine independence by holding a “Fiesta Nacional.” The people held a parade and fired cannons outside the Casa Real (where the present city hall —- inaugurated on Aug. 26, 1940 —-stands). For the first time, the Philippine Flag was raised on Mindanao island.

On March 31, 1900, Companies A, C, D and M of the 40th Infantry Regiment of US Volunteers (USV) invaded Cagayan de Misamis. The regimental commander was Col. Edward A. Godwin. Prior to landing, the Americans bombarded Macabalan wharf, with the flagpole flying the Philippine Flag as the primary target. The wharf was about 5 kilometers distant from the town center.

The Americans set up their barracks in the town center, just beside the present St. Agustine Cathedral.

On Friday, April 6, 1900, a newly formed guerilla force led by General Nicolas Capistrano descended 9 kilometers from their camp in Gango plateau in Libona, Bukidnon Province, Mindanao Island. Numbering several hundred, the guerillas planned to attack the Americans in their barracks.

At dawn of Saturday, April 7, 1900, the bells of San Agustin Church pealed; this was the signal for the guerillas to proceed with the attack. First to attack were the macheteros, who were armed only with bolos; they carried ladders which they used to scale the barracks where the Americans slept. They were followed by the riflemen and cavalrymen who, for the most part, were armed with old rifles.

General Capistrano and his staff stood on the spot where the present water tower stands (constructed in 1922). Capistrano directed his commanders through couriers and hand signals. But his plan for a sneak attack was foiled when Bukidnon lumad (“ethnic minority”) warriors who were among the macheteros, raised battle cries as they killed an American sentry guarding the Chauco Building where the American commander was sleeping.

The noise roused the Americans; they grabbed their weapons and fired at their attackers from the windows of the barracks. Some American soldiers climbed the Church bell tower where they fired at the poorly armed guerillas. The fighting was centered at the town plaza, the present Gaston Park. The battle raged for an hour. The macheteros, who crashed the barracks, engaged the Americans in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Captain Apolinario Pabayo, an officer of the macheteros, was among the first to die. The macheteros‘ leader, Captain Clemente Chacon, tried to climb up the Club Popular Building (the site is now occupied by the St. Agustine Maternity and General Hospital), but was repelled twice and had to scramble down due to a gaping head wound from an American bayonet.

When General Capistrano realized that the attack had gone bad, he ordered a retreat. The Americans pursued the Filipinos to the edge of town.

In his annual report for 1900, Maj. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., listed 4 Americans killed and 9 wounded, and 52 Filipinos killed, 9 wounded and 10 captured. (A Filipino account reported that 200 Filipinos were killed). Later, one of the old streets in the city was named “Heroes de Cagayan” in honor of the Cagayan and Misamis guerillas who took part in the battle. It has since been renamed Pacana Street.

On July 14, 1900, the Americans at Cagayan de Misamis were reinforced by 170 men of the 23rd Infantry Regiment USV and 2 Maxim-Nordenfeldt guns (ABOVE).

BATTLE OF AGUSAN HILL, MAY 14, 1900. Capt. Walter B. Elliott, CO of Company I, 40th Infantry Regiment USV, with 80 men proceeded to the village of Agusan, about 16 kilometers west of Cagayan de Misamis town proper, to dislodge about 500 guerillas who were entrenched on a hill with 200 rifles and shotguns. The attack was successful; 2 Americans were killed and 3 wounded; the Filipinos suffered 38 killed, including their commander, Capt. Vicente Roa. The Americans also captured 35 Remington rifles.

RUFINO DELOSO’S GUERILLA FORCE, MAY 14, 1900 – 1902. Rufino Deloso led a force of 400 guerillas in Misamis Province (in areas that are now in Misamis Occidental) and engaged the Americans in no less than 20 encounters. On March 7, 1902, he surrendered to Senior Inspector John W. Green of the Philippine Constabulary in Oroquieta, Misamis Province. He gave up with 20 riflemen and 250 bolo men.

“CAPITAN” EUSTAQUIO DALIGDIG: Daligdig was a settler from Siquijor Island. He organized a rebel force against Spain, with the town of Daisog (now Lopez Jaena, Misamis Occidental) as his base of operations. “Capitan” Daligdig became a household name throughout Misamis Province; the common folk believed he possessed an “anting-anting” (amulet) that enabled him to fly and made his body impervious to bullets.

The guerilla leader in the Oroquieta-Laungan area led numerous assaults against the Oroquieta Garrison of the Americans.

On Jan. 6, 1901, Daligdig was wounded at Manella, when 40 men of Companies I and E, 40th Infantry Regiment USV, attacked his encampment. Two of his men were killed and 24 captured, but Daligdig managed to escape through the thicket. Later, he availed himself of the general amnesty proclaimed by the US colonial administration on July 4, 1902. He changed his last name to “Sumili” to escape retribution from relatives of civilians he had executed for treason.

BATTLE OF MACAHAMBUS GORGE, JUNE 4, 1900. On Macahambus Gorge, located 14 kilometers south of Cagayan de Misamis (present-day Cagayan de Oro City), Mindanao Island, Filipino guerillas led by Col. Apolinar Velez routed an American force. It is the only known major victory of Filipinos over the Americans on Mindanao Island.

Capt. Thomas Millar, CO of Company H, Fortieth Infantry Regiment USV, led 100 men against the guerillas who were either well-entrenched, or in inaccessible positions, in the gorge. Practically surrounded by an enemy they could not reach, the Americans lost in a short time 9 men killed, and 2 officers and 7 men wounded, nearly all belonging to the advance guard. One Filipino guerilla was killed. An attempt to advance against a part of the Filipino position was frustrated by encountering innumerable arrow traps, spear pits and pitfalls to which an officer and several men owe their wounds. To avoid getting annihilated, the Americans quickly withdrew, leaving their dead and most of the rifles of those killed.

In his official report to the US War Department, Maj. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., censured Captain Millar: “The palpable mismanagement in this affair consists in not having reconnoitered the enemy’s position, but there appears to be no means of reaching a force intrenched, as was this one, in a carefully selected position, which must be approached in single file through a pathless jungle, nor any reason why it should be attacked at all, because, under the circumstances, it does not threaten our troops nor any natives under their protection, and it is sufficient to keep it under observation.”

Velez was born on Jan 23, 1865, to a wealthy family in Cagayan de Misamis. In 1884, he worked as a clerk in the court of first instance of Misamis. From 1886 to 1891, he held the positions of oficial de mesa, interpreter, and defensor depresos pobres. On May 10, 1887, he married Leona Chaves y Roa, thus linking two of the most prominent clans in Misamis.

He enlisted in the Spanish army and became a second lieutenant of infantry. He was decorated with the Medalla de Mindanao.

In 1898, he joined Aguinaldo’s government; he was appointed chief of the division of justice of the Revolutionary Government of Misamis. In 1900, he was assigned the rank of major in the army and appointed as commander of the “El Mindanao” battalion. He later rose to the rank of Colonel.

From 1901 to 1906, Velez held the post of provincial secretary after which he was elected governor of Misamis and served for two terms. In 1928-1931, he served as mayor of Cagayan de Misamis.

He died on Oct. 21, 1939.

GENERAL VICENTE ALVAREZ ATTACKS OROQUIETA, JULY 12, 1900. General Alvarez, who headed the short-lived “Republica de Zamboanga” (May 18, 1899 – Nov. 16, 1899), moved to Misamis Province and assaulted the garrison of Company I, 40th Infantry USV, in Oroquieta on July 12, 1900.

He and his men were repulsed. The Americans reported 2 killed and 1 wounded on their side, and 101 Filipinos killed and wounded.

On Oct. 17, 1900, General Alvarez, his staff and 25 men were surprised in their camp near Oroquieta and captured without a fight by Capt. Walter B. Elliott, commanding officer of Company I, 40th Infantry Regiment USV. The Americans took advantage of the cover provided by the stormy night.

Alvarez was already serving as a high official in the Spanish colonial administration when he turned around and joined the revolution against Spain in March 1898. He led his forces in the successful capture of Zamboanga in May 1898. President and General Emilio Aguinaldo appointed him as head of the revolutionary government of Zamboanga and Basilan.

He was born in 1854 and died in 1910.

April 15, 1900: Battle of Jaro, Leyte

The American barracks at Jaro, Leyte, occupied by a detachment of Company B, 43rd Infantry Regiment of U.S. Volunteers, was attacked at 4:00 a.m. by about 1,000 Filipino guerillas. The detachment commander was 2Lt. Charles C. Estes. [The Company Commander was Capt. Linwood E. Hanson].

The battle lasted for four hours. The Americans reported 125 Filipinos killed, with no casualties on their side.

Jaro is an interior town located 39 kilometers northwest of present-day Tacloban City.

Battle of Catubig, Samar: April 15-18, 1900

On April 15, 1900, 300 Catubig militiamen led by Domingo Rebadulla laid siege on 31 men of Company H, 43rd Infantry of US Volunteers, commanded by Sgt. Dustin L. George, who were quartered in the convent of the Church of St. Joseph. The militia was later reinforced by about 600 men from Gen. Vicente Lukban’s army.

The Americans managed to withdraw to the bank of the river where they entrenched themselves. On the 19th, 1Lt. Joseph T. Sweeney, with a dozen men, effected a landing and brought the hard-pressed soldiers away..

The Americans reported 19 dead and 3 wounded and estimated Filipino losses at 200 dead and many wounded.

The U.S. War Department recorded the event as the heaviest bloody encounter yet for the American troops against the Filipino freedom fighters.

The New York Times called the Battle of Catubig, horrifying.

Cpl. Anthony J. Carson, of Boston, Massachusetts, was given the U.S. highest military award, the Congressional Medal of Honor, for his, according to the citation:

Assuming command of a detachment of the company which had survived an overwhelming attack of the enemy, and by his bravery and untiring effort and the exercise of good judgment in the handling of his men successfully withstood for 2 days the attacks of a large force of the enemy, thereby saving the lives of the survivors and protecting the wounded until relief came.

Domingo Rebadulla was later elected as the first mayor of Catubig under the US regime.

April 16-25, 1900: Major battles in Ilocos Norte

In 7 encounters during the period April 16-25, 1900, 453 of Father Gregorio Aglipay’s poorly-armed men died in action in Vintar, Laoag and Batac. The Americans suffered only a total of 3 men killed in these engagements.

On April 16, Capt. Frank L. French, with a detachment of the 33rd Infantry Regiment of United States Volunteers (USV), known as the “Texas Regiment” because of the popular belief that it was composed of ex-cowboys, struck a body of about 100 Filipinos in the mountains north of Vintar, killing 23 and suffering no casualties.

On the same day, 1Lt. Arthur G. Duncan, commanding 8 men of the 34th Infantry Regiment, USV, met 300 Filipinos with 70 rifles in the mountains near Laoag, killed 29 and captured 22. The Filipinos, upon discovering the smallness of the enemy patrol, went after the Americans.

Duncan and his men retreated toward Batac, where Capt. Christopher J. Rollis prepared for them. The Filipinos, now numbering about 600, made a determined attack, but were repulsed, suffering a loss of 180 killed and 72 prisoners. American casualties were 2 men killed and 3 wounded.

On April 18, Capt. George Allen Dodd, West Point Class 1876, in command of a detachment of the 3rd Cavalry, met a group of 180 Filipinos, with 70 rifles, near Cullebeng. After one hour’s fighting, 53 Filipinos were killed, 4 wounded and 44 taken prisoner. One American was slightly wounded. Captain Dodd also captured 10 horses.

On April 19, 1Lt. Arthur Thayer with a detachment of Troop A, 3rd Cavalry, skirmished with 25 Filipinos near Batac and killed 4. One American soldier was killed.

The Filipinos had 120 killed, 5 taken prisoner and 12 horses captured. The only American casualty was a Sergeant Cook who was slightly cut by a spear.

April 17, 1900: General Antonio Montenegro is trapped, surrenders

April 25, 1900: Marinduque

Marinduque was the first island to have American concentration camps. An American, Andrew Birtle, wrote in 1972: “The pacification of Marinduque was characterized by extensive devastation and marked one of the earliest employments of population concentration in the Philippine War, techniques that would eventually be used on a much larger scale in the two most famous campaigns of the war, those of Brigadier Generals J. Franklin Bell in Batangas and Jacob H. Smith in Samar.”

Marinduque is the site of the Battle of Pulang Lupa, where on Sept. 13, 1900, Filipino guerillas under Col. Maximo Abad ambushed a 54-man detachment of Company F, 29th US Volunteer Infantry, led by Capt. Devereaux Shields. Four Americans were killed, while the rest were forced to surrender.

The defeat shocked the American high command. Aside from being one of the worst defeats suffered by the Americans during the war, it was especially significant given its proximity to the upcoming election between President William Mckinley and his anti-imperialist opponent William Jennings Bryan, the outcome of which many believed would determine the ultimate course of the war. Consequently, the defeat triggered a sharp response.

April 30, 1900: Battle of Catarman, Samar Province

Catarman is a town on the north coast of Samar island, situated on the Catarman River, 55 miles northeast of Catbalogan.

On April 30, 1900, at about 9:30 p.m., Filipino guerillas sneaked into town and attacked Company F, 43rd Infantry Regiment USV. The Americans, commanded by Capt. John Cooke, were garrisoned in the convent of the church.

The Filipinos, estimated to number between 500 and 600 with 100 rifles, drove in the outposts, wounding one US soldier. The rest of the American sentinels retreated into the convent. The Americans decided to wait until daylight. During the night, there was desultory firing on both sides.

At daybreak, May 1, the Americans saw that the Filipinos had built trenches on three sides of the convent. The fourth side, dense with underbrush and cut by a path leading to the beach, was left open. After the battle, the Americans discovered that the path was full of mantraps.

Captain Cooke, leaving word to keep a rapid fire on the trenches, took 30 men and flanked the trenches on the north side of the convent, driving the Filipinos out and killing 52 of them. He then flanked the trenches on the south side, driving the Filipinos out and killing 57, while having one man wounded.

The Americans then made a general move and the Filipinos were completely driven off.

A total of 154 Filipinos were killed, while the Americans suffered only two men wounded.

May 5, 1900: General MacArthur becomes VIII Army Corps Commander and Military Governor of the Philippines

On May 5, 1900 Maj. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr. replaced Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis as VIII Army Corps Commander and Military Governor of the Philippines.

He moved into the Malacaan Palace, a Moorish edifice by the Pasig river which had served as the residence of the Spanish governors-general. His military command, the Division of the Philippines, the largest in the Army at the time, included 71,727 enlisted men and 2,367 officers in 502 garrisons throughout the country.

June 15, 1900: General Francisco Makabulos surrenders

He turned over the large amount of Mexican currency which he had captured from the Spaniards. He need not have to, and nobody would been the wiser, but Makabulos apparently was a man of high integrity.

His surname means “one who prefers to be free.” Born in La Paz, Tarlac, on Sept. 17, 1871, he was the son of Alejandro Makabulos, a native of Lubao, Pampanga, and Gregoria Soliman, a native of Tondo, Manila. His mother was a descendant of Rajah Soliman, hero of the 1571 battle of Bangkusay, Manila.

He had no formal education; he learned to write and speak Spanish from his mother. He had an excellent penmanship and served as parish clerk for the town priest for many years.

With the help of Don Valentin Diaz, one of the founders of the Katipunan, he propagated the tenets of the secret revolutionary society throughout Tarlac Province. Makabulos organized his friends and kin into arnis (“fighting stick”) and bolo brigades. He started with 70 men, which soon grew in number as people from the nearby towns of Tarlac, Capas, Bamban and Victoria rallied under his banner. On Jan. 24, 1897, Makabulos and his bolo brigades raised the “Cry of Tarlac” and took over the municipal hall of La Paz during the town fiesta celebration.

In June 1897, in Mt. Puray, Montalban, Morong (now Rizal Province), General Emilio Aguinaldo promoted Makabulos to General of all revolutionary forces in Pampanga, Tarlac, and Pangasinan. He set up his encampment in sitio Kamansi on the slopes of Mt. Arayat. In November 1897, an assault by a massive Spanish force commanded by General Ricardo Monet dislodged him from his Sinukuan sanctuary.

The Revolution temporarily ceased following the Dec. 14, 1897 Truce of Biyak-na-Bato. His fellow rebel leaders went on exile in Hong Kong but Makabulos distrusted Spanish intentions; he made preparations for the resumption of the revolution. On April 17, 1898, in Lomboy, La Paz, he set up his Central Directive Committee of Central and Northern Luzon, often referred to as the Makabulos Provisional Government. It functioned under a constitution, the “Makabulos Constitution”, which he himself drafted.

He rallied to General Emilio Aguinaldo when the latter returned and renewed the struggle on May 19, 1898. On July 10, 1898, he liberated Tarlac Province from Spanish rule. On July 22, 1898, he liberated Pangasinan Province. He was appointed to the Malolos Congress which opened on Sept. 15, 1898, representing the province of Cebu.

Makabulos was a founding member of the pro-American Partido Federal when it was organized on Dec. 23, 1900.

He was elected municipal president of La Paz in 1908, and later served as councilor of Tarlac, Tarlac.

Makabulos became locally famous as a writer of zarzuelas (plays that alternate between spoken and sung scenes). Among his works were “Uldarico” and “Rosaura.” He also wrote a zarzuela out of Balagtas “Florante at Laura.” He translated the opera “Aida” into Tagalog.

He died of pneumonia in Tarlac on April 30, 1922 at the age of 51.

Sept. 17, 1900: Filipino victory at Mabitac. Laguna

Mabitac is a municipality situated on the eastern side of the province of Laguna.

The battle began when the Americans came under intense fire some 400 yards from the Filipino trenches. Eight troopers sent ahead to scout the Filipino positions were all killed. One of the last to fall was 2nd Lieutenant George Cooper. General Cailles, in an honorable gesture, allowed Cheatham to retrieve the bodies of his men.

The main body of the U.S. Infantry got pinned down in waist-deep mud, still several hundred yards from the Filipino trenches. Captain John E. Moran was later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for trying to rally his demoralized comrades.

Supporting fire from a US Navy gunboat (some 1,300 yards distant) and a flank attack by 60 Americans failed to dislodge the Filipinos from their positions.

Cheatham withdrew, re-consolidated his forces and prepared to launch another offensive.

General Cailles ordered a withdrawal in order to avoid envelopment, and by the next day, his entire command had made good its escape.

The Americans lost 21 killed and 23 wounded; the Filipinos suffered 11 killed and 20 wounded. Among the Filipino dead was Lieutenant Colonel Fidel Sario.

American Major-General John C. Bates later said of this battle: “It is deemed charitable as well as politic to drop a veil over this matter rather than to give any publicity that can be avoided.”

Oct. 14, 1900: Battle of Ormoc, Leyte Island

On Oct. 14, 1900, Company D of the 44th Infantry Regiment USV, commanded by 1Lt Richard W. Buchanan, clashed with Filipino guerillas in Ormoc, Leyte Island. The Americans suffered no casualties, while 116 Filipinos were killed.

Oct. 24, 1900: Ambush at Cosocos, Ilocos Sur Province

On Oct. 24, 1900, an American force consisting of 40 men of Company H, 33rd Infantry Regiment USV, and 2Lt. Grayson Heidt, with 60 men of Troop L, 3rd Cavalry, left Narvacan, Ilocos Sur Province, under the command of 1Lt. George Febiger, 33rd Infantry, to attack the Filipinos at barrio Cosocos, Nagbukel town, Ilocos Sur, about 22 kilometers away.

The last 3 kilometers of the road is through a canyon with precipitous walls. Within 300 meters of barrio Cosocos, the point man discovered and opened fire on the Filipinos, estimated to number 400 and commanded by Juan Villamor. They were in position on both sides of the canyon and entrenched in front. After half an hour’s engagement, seeing the Filipinos had the advantage in numbers and position, the precipitous sides of the canyon preventing a flanking movement, Lieutenant Febiger ordered a retreat. The Americans were compelled to fight their way out of the canyon, Lieutenant Febiger taking the advance and Lieutenant Heidt the rearguard.

Within 800 meters outside the mouth of the canyon, Lieutenant Febiger was killed; an attempt was made to carry his body along, but owing to the aggressiveness of the Filipinos his body had to be left on the field.

As the firing was at close range for most of the time, the Americans estimated Filipino losses in killed and wounded at over 100. [Maj. Gen. Adnan R. Chaffee reported that 50 Filipinos were killed and 100 wounded.]

Total American losses were 5 killed, 14 wounded and 8 captured (released the following day by Juan Villamor). The Americans also lost 9 rifles, 1 carbine and 24 horses.

Feb. 2, 1901: General Martin Delgado surrenders

An American historian wrote, “As a result of this surrender, 41,000 inhabitants of the Province of Iloilo took the oath of allegiance.”

March 8, 1901: Massacre at Lonoy, Bohol

Lonoy was a hilly barrio of Jagna town, Bohol Island. It was about 10 kilometers from the poblacion.

There were two Filipino guerilla encampments on Mt. Verde in Barrio Lonoy.

Miguel Valmoria’s campsite was in the upper part of Lonoy, while Capt. Gregorio “Goyo” Caseas’ was in the lower part of the village. [LEFT, monument to Gregorio Casenas at Lonoy, photo by Onil Berro]

On March 5, 1901 Valmoria received a communication from the general headquarters of Bohol guerilla leader, Pedro Samson, that the Americans had started moving towards his (Valmoria’s) camp.

Valmoria warned Caseas that his camp (Caseas’) will be first to be attacked. Believing that the American troops will pass through Lonoy via a narrow path, Caseas and his men dug trenches and foxholes on both sides of the path, covered and camouflaged. Waiting in the trenches and foxholes were 413 guerillas, nearly all armed only with daggers, bolos and spears.

Unknown to them, the Americans had learned of the ambush plan from a pro-American native, Francisco Salas, who led the Americans to the rear of the Filipino defenses.

On March 8, 1901, the Americans struck from behind, catching the would-be ambushers totally offguard; they shot and bayoneted the guerillas to death in their trenches; the Americans had received orders not to take prisoners and any Filipinos attempting to surrender were gunned down

When the smoke cleared, 406 of the Bohol natives lay dead on the ground, including

Caseas, and only 7 survived.

The Americans suffered 3 killed and 10 wounded.

March 10, 1901: General Mariano Riego de Dios surrenders

Riego de Dios was born on Sept. 12, 1875 in Maragondon, Cavite. He became a member of the Katipunan on July 12, 1896. He was among the first Caviteos to join the revolutionary society. In October 1896, he was among the Katipuneros who attacked the Spanish garrison in Lian, Batangas. He was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General after the triumphant defense of Noveleta, Cavite in 1896.

He was member of the council of war that tried and convicted the Bonifacio brothers (Andres and Procorpio) of sedition and treason against the revolutionary government of Emilio Aguinaldo. The brothers were sentenced to death but Riego de Dios believed the sentence was harsh and abstained from signing the death verdict.

He died on Feb. 17, 1935. Camp General Mariano Riego de Dios in Tanza, Cavite was named in his honor.

March 15, 1901: General Mariano Trias surrenders

General Mariano Trias was born on Oct. 12, 1868 in San Francisco de Malabon (now General Trias), Cavite province. He went to Manila and enrolled at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran for his Bachelor of Arts, then to the Universidad de Santo Tomas for his course in Medicine, which he was unable to finish as he returned home to help his parents manage the farm holdings.

He joined the Katipunan before the revolution broke out on Aug. 30, 1896 and became an active propagandist of the society against the ruling Spaniards in the towns of Silang and Kawit.

On Nov. 1, 1897, the Biak-na-Bato Republic was established. Emilio Aguinaldo was president and Tras was vice president.

On Jan. 23, 1899, with the establishment of the Philippine republic, he was appointed as Secretary of Finance. He later held the post of Secretary of War. After Filipino forces were practically dispersed in Central Luzon by the US army, he was named commanding general of Southern Luzon. He directed guerrilla offensive moves in Cavite province.

He figured in a series of furious skirmishes with the troops of Brig. Gen. Lloyd Wheaton in January 1900 when he defended Cavite until his men were finally dispersed. General Tras set free all the Spanish prisoners under his command in May 1900.

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr., viewed this as “a most auspicious event, indicating the final stage of armed insurrection. The prestige of Trias in southern Luzon was equal to that of Aguinaldo.”

With the establishment of the civil government by the Americans, Civil Governor William Howard Taft appointed him the first Civil Governor of Cavite on June 11, 1901 and he served until 1905.

In late January 1905, Julian Montalan, one of Macario Sakay’s generals, raided San Francisco de Malabon. The guerillas overcame the constabulary force and captured their weapons. In departing, they kidnapped the wife and two small children of Governor Trias.This action was taken in response to Trias’s collaborationist policies and his arrest of those suspected of aiding the guerillas. Trias was the actual target but he managed to escape by jumping through a window and submerging himself in a canal, which flowed in the rear of his premises. His wife was reportedly abused and one of her ribs broken by the butt of a gun. The family was recovered shortly thereafter by the Constabulary.

Trias organized the first chapter of the Nacionalista Party in Cavite. He was a member of the honorary board of Filipino commissioners to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904. He was acting governor of Cavite when he died of appendicitis at the Philippine General Hospital on Feb. 22, 1914.

Jasmine Trias of American Idol fame is his descendant. She placed 3rd in the 2004 season of the top-rated show. Jasmine was born in Honolulu, Hawaii on Nov. 23, 1987. She is the eldest daughter of Filipino immigrants from Tanza, Cavite.