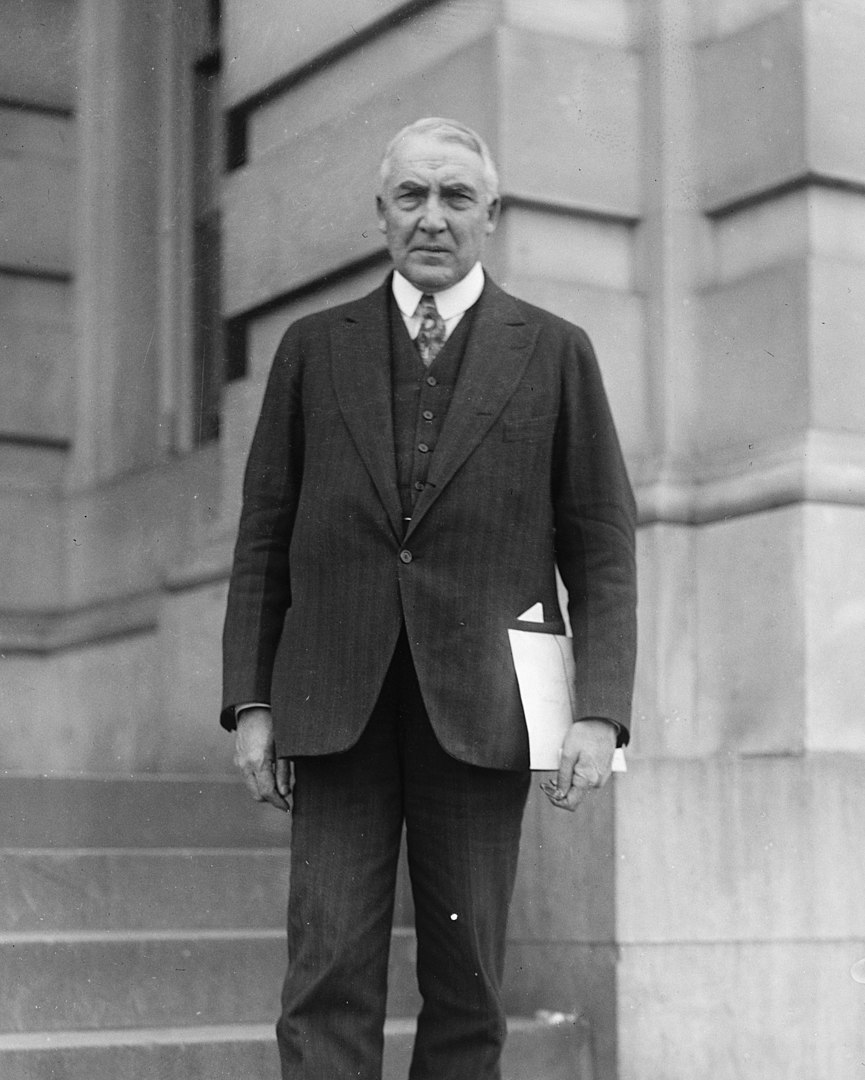

Warren Harding was born in Corsica, Ohio, on November 2, 1865. George Tyron Harding and Phoebe Elizabeth Dickerson were his parents. Presidents George Washington, Calvin Coolidge, George Herbert Walker Bush, George W. Bush, Princess Diana, and Sir Winston Churchill are all descended from William Talvas Montgomery Le Despenser, who was born in 1100 in Lincolnshire, England.

Florence Mabel Kling Harding

Florence Mabel Kling DeWolfe was born on August 15, 1860, in Marion, Ohio, to a wealthy family. Her parents were Louisa Mabel Hanford Bouton and Amos Kling, and she was the eldest among their three children. Florence married Henry DeWolfe at nineteen years old. She did, however, leave her husband soon after having a son. She supplemented her income by teaching piano lessons.

Florence Kling studied classical piano in Marion for years, later stating that her goal at the Cincinnati Conservatory was to become an internationally recognized concert pianist. On the other hand, her father saw it as a practical step that would enable her to “earn her living if she was ever thrown upon her own capital” as a piano instructor.

She started her lessons in French as well. According to founder Clara Baur, the conservatory can “fit young people for professional careers or social positions as circumstances dictate, by using the highest culture of the art of music, that they will wield a more powerful influence for the good.” Warren Harding’s sister was one of her pupils.

On July 8, 1891, she and Harding were married. Florence contributed to the growth of Warren Harding’s newspaper. Florence and Warren didn’t have any children of their own, but Florence’s son Marshall stayed with them on occasion and was encouraged by Warren to pursue a journalism career.

She did not write or edit reports. Still, she did make editorial decisions, such as directing reporters to cover specific events, offering leads and sources, and seeking out human interest stories. She also recruited Jane Dixon, the state’s first female reporter. She gained the male staff’s support and admiration without exerting any effort or resistance.

She was also a famous and active first lady who hosted several well-attended events. She welcomed the public into the White House.

Unlike every previous presidential candidate’s wife, Florence Harding expressed her political beliefs, most notably her vehement anti-League of Nations and pro-suffrage views. She believed that women’s right to vote was a foregone conclusion, but she used personal stories to discuss jobs, economic and social equality. She structured her words to wrongly say that she was a widow when she married Harding to answer her first marriage questions.

Florence Harding and two carloads of Harding’s papers in long wood boxes left the White House on August 17, 1923, for the McLean estate, “Friendship.” She and Evalyn McLean examined what they considered to be repetitive, excessive, could be potentially misconstrued, or was outright damaging. It’s also safe to assume that she destroyed many of her First Lady Office papers, the documentary evidence for patchy. On September 5, 1923, Florence returned to Marion, Ohio, for a brief visit, where Florence continued to arrange and cull Harding’s letters. She didn’t get rid of the majority of them or even anything potentially dangerous.

Florence Harding remained politically involved even in her final weeks. She lobbied President Coolidge to appoint Hoke Donithen, a Harding attorney, to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, with Ohio’s two senators’ help. He flatly declined. When she asked for his forgiveness for her late voter registration in 1924, he responded with similar obstinacy. Her last public appearance was at a Marion Armistice Day (now Veterans’ Day) parade, where she stood in her car in the pouring rain to salute the World War I veterans who passed by.

On November 21, 1924, she died at the age of 64 in Ohio and was buried at The Harding Memorial, Marion, Ohio.

Elizabeth Ann Britton Harding Blaesing

Elizabeth Ann Britton Blaesing Harding was the illegitimate daughter of Warren G. Harding and Nan Britton, a native of Marion, Ohio. She was born on October 2, 1919.

Nan Britton, her mother, wrote The President’s Daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, who did not seek historical fame, became popular. The publication of the book in 1927 sparked a lot of debate. Britton claimed to have been President Warren G. Harding’s lover and the mother of his only biological child, Elizabeth Ann, in the letter. The claim was surprising enough on its own, but Britton went into such graphic detail that her book was temporarily banned as obscene. Before withdrawing from public view, Nan Britton argued that Elizabeth Ann was Harding’s successor and real legacy for years.

Partisans of the late President spent years claiming that Nan Britton’s story was fake, if not outright slanderous. Scholars have disagreed about the book’s authenticity and authorship. In a national argument about the people’s character and the legitimacy of considering a President’s private life when judging his legacy, the rhetoric was venomous. In the end, few people emerged from the discussion with a clean slate.

When Warren Harding scholar Dr. Robert H. Ferrell, author of The Strange Death of President Harding, and later John Dean, author of Warren Harding, The American President Series, approached him, Elizabeth Blaesing declined.

Elizabeth Blaesing died on November 17, 2005, in Oregon. The family did not make a public announcement about her death. According to Cleveland Plain Dealer, her son Thomas Blaesing confirmed it in a May 2006 interview with the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Blaesing’s son claims that his mother was uninterested in obtaining DNA proof to prove paternity. The mystery may also be solved by testing on Blaesing’s sons or grandchildren. Some academics, including bioethicist Jacob Appel, have argued that the Blaesings have a “moral and civic duty” to provide their DNA for comparative research.

US Presidents | ||