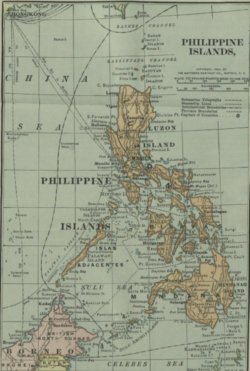

The Philippines (LEFT, 1898 map) was a colony of Spain from 1571 to 1898. Spanish rule came to an end as a result of the Philippine Revolution and US involvement with Spain’s other major colony, Cuba.

The Philippine archipelago, with a total land area of 300,000 sq km (115,831 sq mi), comprises 7,107 islands in the western Pacific Ocean, located close to the present-day countries of Indonesia, Malaysia, Palau and the island of Taiwan.

The capital, Manila, is 6,977 miles (11,228 km) distant —- “as the crow flies” —- across the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco, California, U.S.A. The two cities are separated by 6,061 nautical miles of water.

Luzon and Mindanao are the two largest islands, anchoring the archipelago in the north and south. Luzon has an area of 104,700 sq km (40,400 sq mi) and Mindanao has an area of 94,630 sq km (36,540 sq mi). Together, they account for 66% of the country’s total landmass.

Only nine other islands have an area of more than 2,600 sq km (1,000 sq mi) each: Samar, Negro-s, Palawan, Panay, Mindoro, Leyte, Cebu, Bohol and Masbate.

More than 170 dialects are spoken in the archipelago, almost all of them belonging to the Borneo-Philippines group of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family.

Twelve major dialects � Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, Ilonggo, Bicol, Waray, Pampango, Pangasinense; Southern Bicol, Kiniray-a, Maranao, Maguindanao and Tausug (the last three in Muslim areas of Southern Philippines) � make up about 90% of the population.

The population in 1898 was about 9 million.

The Cubans had set up propaganda in the United States to support their cause for independence; the Cuban community had built connections with senators, congressmen and with the press.

American business interests were perturbed by the tumult in Cuba; in addition, public opinion in the US became aroused by newspaper accounts of the brutalities of Spanish rule. These reports were not exaggerated: between 200,000 and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in Spanish concentration camps.

The 1890’s were marked by mounting efforts in the United States to extend American influence overseas. These were often justified by references to Manifest Destiny, a belief that territorial expansion by the United States was both inevitable and divinely ordained; this belief enjoyed widespread support among U.S. citizens and politicians.

The spirit of imperialism growing in the United States�fueled by supporters of Manifest Destiny�led many Americans to believe that the United States needed to take aggressive steps, both economically and militarily, to establish itself as a true world power.

Fearing U.S. intervention in Cuba, Spain moved to a more conciliatory policy, promising home rule with an elected legislature. The Cuban rebels rejected this offer and the war for independence continued.

The Philippine Revolution, led by Andres Bonifacio, broke out on Aug. 30, 1896. The rebels attacked but failed to capture the Spanish powder depot and water reservoir in San Juan del Monte, a suburb of Manila; 153 rebels and 2 Spanish soldiers died in the fighting that spilled over into the adjacent Santa Mesa district of Manila. Uprisings in other places took place shortly thereafter.

Hundreds of suspects were arrested, questioned under torture, imprisoned or deported to the Carolines or to the Spanish island colony of Fernando Po in faraway Africa. [The Caroline Islands are found in the western Pacific Ocean, northeast of New Guinea. At present, they are divided between Micronesia and Palau. This area was also called Nuevas Filipinas or New Philippines as they were part of the Spanish East Indies and governed from Manila. Fernando Po Island, where 151 Filipinos were deported on Oct. 14, 1896, is now known as Bioko in the Republic of Equatorial Guinea.]

A great number of Filipinos were executed at the Luneta in Manila or elsewhere.

Nevertheless, despite the repression, tortures and executions, the revolution continued to spread throughout the archipelago.

Bonifacio, a gifted public speaker and mass organizer but a poor combat tactician, faltered in battle. On the other hand, the reticent Emilio Aguinaldo, the second leading personality in the revolution, made others do the political work for him; what he lacked in charisma, he made up for with an innate military acumen. He scored spectacular victories over the better-armed Spaniards in Cavite —- the heartland of the revolution —- and except for the Cavite peninsula, had gained control over the entire province.

A power struggle ensued between Aguinaldo and Bonifacio, the contentious issue being who was abler to lead the war for freedom.

General Blanco tried to maintain Spanish control by shifting to a more conciliatory policy. He declared to the effect that it was not the purpose of his Government to oppress the people and he had no desire “to slaughter the Filipinos.”

The new benign strategy did not sit well with the Spanish friars. They wanted the restive Filipinos to be flogged into submission.

Manila Archbishop Bernardino Nozaleda and the religious orders worked hard behind the scenes to get Blanco ousted. They used all possible means, including bribery, to bring about his dismissal.

The friars believed that Blanco’s newly arrived second-in-command, General Camilo Garcia de Polavieja, would be easier to impress with their point of view.

They sent a telegram to their cohorts in Madrid.

The telegram read thus :

“Situation more grave. Revolt spreading. Apathy of Blanco unexplainable. To remove danger, an urgent necessity is the appointment of a new governor-general. Opinion unanimous, Archbishop and Provincials.”

They included Polavieja’s name in the shortlist of nominees submitted to the Queen Regent.

On Dec. 13, 1896, Polavieja (ABOVE, ca 1896) replaced Blanco as Governor-General.

He proved to be as brutal as his counterpart Valeriano Weyler was in Cuba. Under his direction, the Spanish soldiers seldom took prisoners; civilians were herded into cramped concentration camps. Many died from ill-treatment, disease, and starvation.

Polavieja also ordered the execution of the non-militant reformist Jose Rizal and 24 others.

[One of the martyrs was a pure Spaniard, Moises Salvador. An Insulare (Philippine-born Spaniard), he was born in Quiapo, Manila on Nov. 25, 1868. He walked barefooted to his death spot on the field while calmly smoking a cigar. Guipit Elementary School (founded in 1915) in Sampaloc district, Manila, was renamed Moises Salvador Elementary School in his honor on July 13, 1936].

[2Lt. Benedicto Nijaga and Cpl. Cristobal Medina were native Filipino members of the Spanish army. Nijaga Park in Calbayog City, Samar Province, was named in Lieutenant Nijaga’s honor].

When the revolution broke out in August 1896, there were about 1,500 Spanish troops posted in the Philippines. Their native auxiliaries numbered around 6,000. Reinforce- ments from Spain were received beginning in October 1896.

By January 1897, a total of 25,462 officers and men had arrived from Spain. Governor Polavieja had an available force of over 12,000 to suppress the rebels in Luzon island, where the insurrection was most active.

His plan for 1897 had two phases: first, “pacify” the zones separated from Cavite, and then to make an offensive campaign against that province. Accordingly, the month of January saw the fully-loaded Spanish forces successfully attacking the scantily-armed rebels in the provinces of Bulacan, Morong, Bataan, Zambales, Laguna and Batangas. By January 22, Spanish field commanders reported that no rebel force could be found in all Batangas, and the same was reported from Bataan and Zambales.

On Feb. 13, 1897, Governor Polavieja opened his Cavite campaign and threw 9,277 troops in a full offensive against Aguinaldo. They were led by General Jose Lachambre, Deputy Commander of the Spanish forces.

The important towns of Silang, Dasmarinas, Imus and Bacoor fell in quick succession.

General Jose Lachambre and aides-de-camp, 1897.

By the middle of March 1897, General Lachambre had dispersed almost every rebel contingent of any importance in the province.

On March 22, 1897, rebel delegates met at Barrio Tejeros, San Francisco de Malabon (now General Trias), Cavite, to plot the defense of the beleaguered province. But once the convention opened, the agenda changed: Bonifacio was voted out as rebel chief, Aguinaldo took his place, and the revolutionary organization underwent a total makeover.

On April 23, 1897, he was replaced by Fernando Primo de Rivera (LEFT, in 1897).

Meanwhile, Andres Bonifacio’s subsequent actions following his ouster led to his execution by Aguinaldo on May 10, 1897.

A few days after Bonifacio’s death, Aguinaldo and his men, sorely lacking weapons and ammunition, abandoned Cavite to avoid total destruction by massive Spanish offensives. The intact rebel army moved to Talisay, Batangas Province, with the Spaniards in hot pursuit.

The Spanish forces surrounded Talisay in the hope of capturing Aguinaldo, but he slipped through the cordon on June 10 and proceeded with 500 handpicked men to the hills of Morong Province (now Rizal). He crossed the Pasig River to Malapad-na-Bato, near Guadalupe, passed through San Juan del Monte and Montalban, and on to Mount Puray.

After a short rest, Aguinaldo and his men proceeded to Biyak-na-Bato, San Miguel de Mayumo, Bulacan Province, where he established his headquarters.

He joined forces with General Mariano Llanera. The Filipinos’ new base of operations was located in the heavily-forested foothills of the Sierra Madre mountain range.

From Biyak-na-Bato, Aguinaldo harassed the Spanish soldiers garrisoned in the Central Luzon Provinces.

The Filipino rebels also established what is now known as the Biyak-na-Bato Republic.

The provisional constitution of this Republic was prepared by Felix Ferrer and Isabelo Artacho, who copied, almost word for word, the Cuban constitution of Jimaguayu. The Biyak-na-bato Constitution was signed on Nov. 1, 1897. Its preamble states:

“The separation of the Philippines from the Spanish monarchy and their formation into an independent state with its own government called the Philippine Republic has been the end sought by the Revolution in the existing war, begun on the 24th of August, 1896; and , therefore, in its name and by the power delegated by the Filipino people, inter- preting faithfully their desires and ambitions, we the representatives of the Revolution, in a meeting at Biac-na-bato, November 1, 1897, unanimously adopted the following articles for the constitution of the State.”

Governor Rivera was frustrated by his failure to crush the Filipino revolutionaries. The Madrid government had already sent over 50,000 cazadores to the Philippines together with several artillery, cavalry, engineer and supporting units, way above the 20,000 troops that the Colonial government had originally estimated it needed to crush the uprising.

Rivera asked for more troops but the home government declined; massive commitment in the Cuban revolution had already tied down more than 150,000 soldiers. Reluctantly, he agreed to negotiate for a truce and perhaps even a settlement of the conflict with the Philippine Independence movement.

The colonial government and the Filipinos knew that to continue hostilities meant an inconclusive war of attrition. The standoff in the battlefield prompted both sides to explore the prospects of an armistice. A mestizo lawyer, Pedro Paterno, volunteered to act as mediator between the two sides. For four months, he traveled between Manila and Biyak-na-Bato.

On Dec. 14, 1897, the Pact of Biyak-na-Bato officially halted hostilities.

The Pact ordered Aguinaldo and other major revolutionaries to be exiled and live peacefully in Hong Kong, where they would be paid $800,000 in Spanish-Mexican currency (read as “pesos”; the symbol used for the peso was “$”, basically the same as for the US dollar). Spain would grant an “ample and general amnesty” to the remaining revolutionaries pending they forfeit their arms.

The Pact alluded to “the desire of the Filipino people for reforms”, like the suppression and eventual expulsion of the tyrannical and oppressive Friars, secularization of the religious orders, and establishment of an autonomous political and administrative government. [By special request of Governor-General Rivera, these specific conditions were not put down in writing, owing to his assertion that otherwise the Treaty would be in too humiliating a form for the Spanish Government, while on the other hand he guaran- teed on his word as gentleman and officer the fulfillment of the same].

In conclusion, $900,000 was to be paid to the citizens of the Philippines, who suffered greatly from the effects of the war.

The Pact, however, was an empty promise for both parties; they were only biding time until they could launch another offensive. Spain had no intention to fully pay up or grant reforms. Comparatively, Aguinaldo planned to use the money to buy arms and ammu- nition and revivify the revolt. Thereafter, Spain actually delivered a mere $600,000 out of the $1,700,000 promised. Filipino prisoners were released on amnesty then rearres-ted on fabricated charges; more than two hundred men were executed. On the other hand, the arms turned in by the rebels consisted of old or broken rifles and pistols, and guns made of bamboo and wrapped in metal.

Two months later, on Feb. 14, 1898, the exiles effectively repudiated the truce when they undertook to buy arms in Shanghai and Hong Kong to resume the revolution. It had become clear that, as expected, the Spanish authorities would not abide by the terms of the Treaty. [Aguinaldo had also received a letter from Lt. Col. Miguel Primo de Rivera, nephew and private secretary of Governor Rivera, informing him that neither he nor his companions could ever return to Manila].

Then fate intervened on the other side of the globe.

On Feb. 15, 1898, at 9:30 p.m., a mysterious explosion sank the American battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbor, killing 266 of the 354 crew members.

With no proof, purveyors of the “Yellow Press” accused the Spanish of blowing up the ship (although Spain had no motive for doing so). “Remember the Maine” became a call to arms for Americans.

On April 25, 1898, the U.S. Congress voted for war against Spain.